New steps are needed to improve sovereign debt workouts

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly lengthened the list of developing and emerging market economies in debt distress. For some, a crisis is imminent. For many more, only exceptionally low global interest rates may be delaying a reckoning. Default rates are rising, and the need for debt restructuring is growing. Yet new challenges may hamper debt workouts unless governments and multilateral lenders provide better tools to navigate a wave of restructuring.

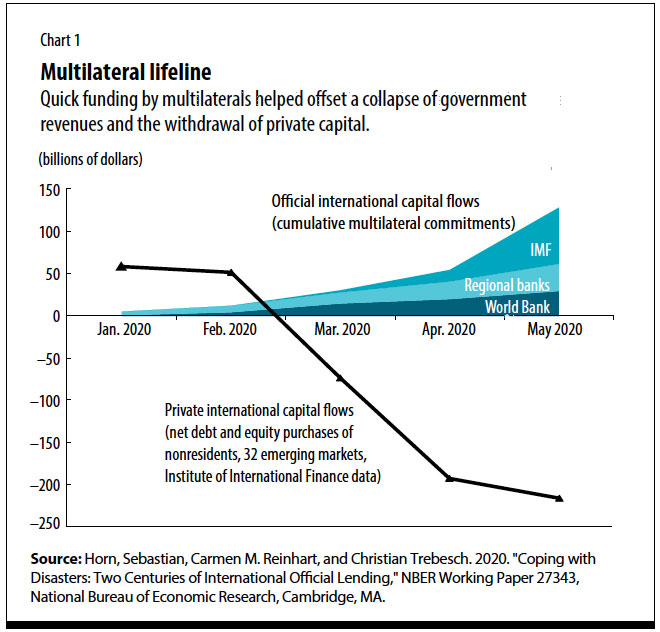

The IMF, the World Bank, and other multilaterals acted quickly to provide much-needed funding amid the pandemic as government revenues collapsed alongside economic activity, while private capital flows came to a sudden stop (see Chart 1). In addition to new loans from multilaterals, Group of Twenty (G20) creditors granted a debt moratorium to the world’s poorest countries. They have encouraged private lenders to follow suit—albeit with little success.

So far, the pandemic shock has been limited to the poorest countries and has not morphed into a full-blown middle-income emerging market debt crisis. Thanks in part to favorable global liquidity conditions conferred by massive central bank support in advanced economies, private capital outflows have moderated and many middle-income countries have been able to continue to borrow in global capital markets. According to the IMF, emerging market governments issued $124 billion in hard currency debt during the first six months of 2020, with two-thirds of the borrowing coming in the second quarter.

Yet there are still reasons for concern about sustained emerging market access to capital markets. The riskiest period may still lie ahead. The first wave of the pandemic is not over. Experience from the 1918 influenza pandemic suggests the possibility of an even more severe second wave, especially if it takes until mid-2021 (or later) for an effective vaccine to become widely available. Even in the best-case scenario, international travel will face roadblocks, and uncertainty among consumers and businesses is likely to remain high. World poverty has risen sharply, and many people will not be returning to work when the crisis passes. The political ramifications of the crisis in advanced economies are also still unfolding. The backlash against globalization, already rising before COVID-19, may intensify.

Although many emerging market governments have succeeded in borrowing more in local currencies, businesses have continued to accumulate foreign currency debt. Under severe duress, it’s likely that emerging market governments would yield to pressure to bail out their corporate national champions, just as the United States and Europe have done.

On top of the dramatic retreat in private funding, remittances from emerging market citizens working in other countries are expected to drop by more than 20 percent this year. At the same time, borrowing needs have skyrocketed, as emerging market and developing economies contend with the same budgetary stresses as advanced economies. Health systems must be strengthened and support must be provided for citizens whose lives are affected most acutely. Borrowing needs will only rise further as the economic damage mounts.

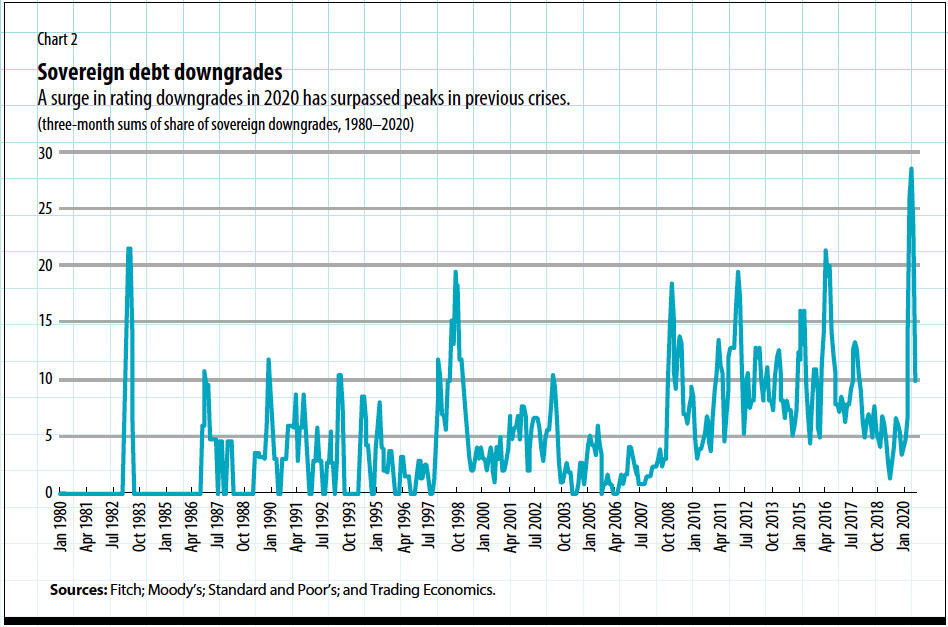

Rising budget pressures have been accompanied by a new wave of sovereign debt downgrades, surpassing peaks during prior crises (see Chart 2). They have persisted even as major advanced economy central banks have eased credit conditions. Central bank purchases of corporate bonds to provide support for local firms in emerging market and developing economies have also handicapped their debt ratings.

History shows that it is not unusual that countries can keep borrowing even when default risk is high. A review of 89 default episodes from 1827 to 2003 shows the typical experience to be a sharp rise in borrowing, both external and domestic, in the run-up to default (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009). Ideally this time will be different, but the record is not encouraging.

Amid massive and synchronous financing needs across a broad swath of countries, there is brewing in the background a growing need for debt restructurings in numbers not seen since the debt crisis of the 1980s. Official creditors should be prepared to act as needed.

Here they will be impeded by two trends that have been developing independently of the COVID-19 crisis. Call them “preexisting conditions.”

First, private creditors are increasingly claiming outsize shares of repayment in debt restructurings. Although theoretically the official sector is a senior creditor to the private sector, much of the historical experience suggests otherwise.

During the 1980s emerging market debt crisis, private creditors were quite successful at pulling out funds as official creditors went in ever deeper (Bulow, Rogoff, and Bevilaqua 1992). Similar developments were at play during the European debt crisis, when investors did take some losses in Greece; a large portion of their funds had been pulled out, with repayments facilitated by large-scale loans by euro area governments (Zettelmeyer, Trebesch, and Gulati 2013). This pattern has recurred over two centuries of private and official lending: when private investors retrench, official lenders often step in (Horn, Reinhart, and Trebesch 2020, cited in Chart 1).

A recent analysis comparing losses (haircuts) taken by official and private creditors raises further doubt about the supposed seniority of official sector loans (Schlegl, Trebesch, and Wright 2019).

These outcomes should not be surprising. After all, governments have a history of protecting domestic creditors who lent abroad (think northern European banks in the case of Greece), and at the same time also care about stability and welfare in the borrowing country. Such altruism, in turn, weakens the official sector’s bargaining position—especially vis-à-vis private creditors. Thus, official creditors may be left holding the bag for the bulk of the losses, even when they start with little of the outstanding debt, as in Greece.

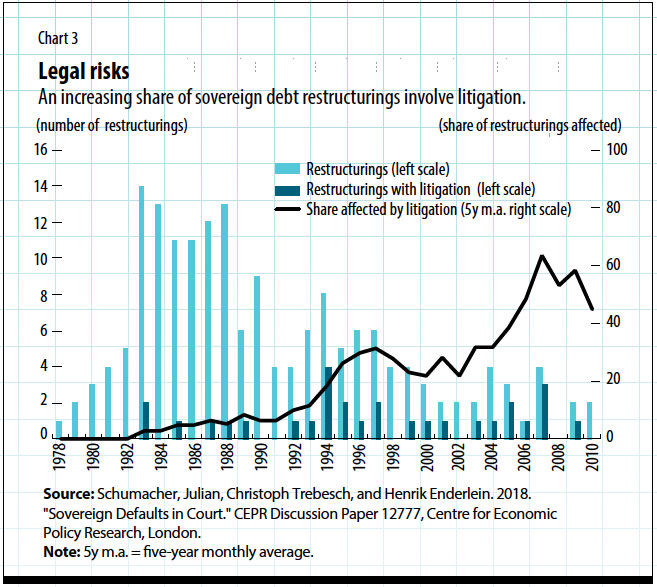

A further challenge comes from new holdout and litigation tactics by private investors to resist large debt write-downs and restructurings. As the number of restructurings has declined, an increasing share of them have involved lawsuits (see Chart 3, from Schumacher, Trebesch, and Enderlein 2018). While this may not completely explain the private sector’s success in maximizing its share in debt restructuring, it is disconcerting.

The second preexisting condition is the length of time debt crises are dragging on. As former Citibank chairman William Rhodes famously said during the debt crisis of the 1980s: “It is easy to get into a debt moratorium. It’s tough to get out.”

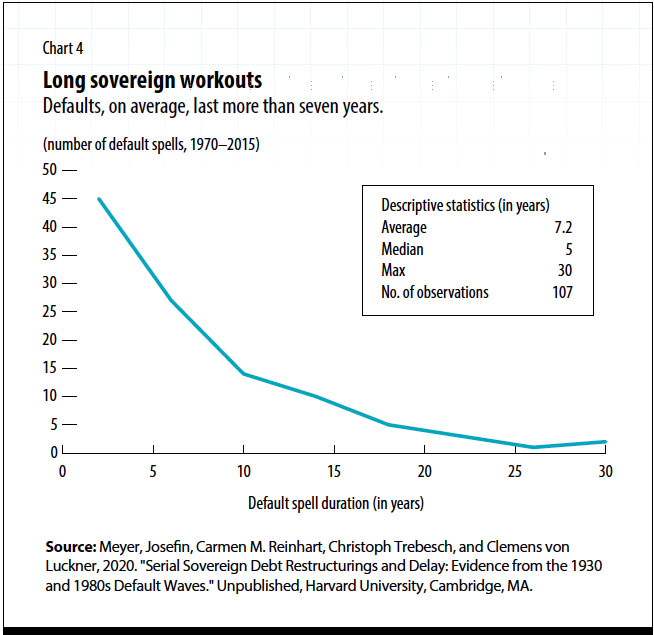

Default episodes have taken, on average, seven years to resolve and typically involve multiple restructurings (see Chart 4). Unfortunately, debt restructurings can become a bargaining game in which the country debtor is often (rightly) willing to exchange higher future debt for lower payments now, fully intending to restructure debt again as necessary. Delay also helps both sides bargain for larger infusions from official creditors (Bulow and Rogoff 1989). And creditors may often be willing to repeatedly renew (or “evergreen”) debt in order to temporarily make their balance sheets look better. The COVID-19 crisis could, in the worst case, lead to another “lost decade” in development, with long delays in debt resolution.

What can governments and multilateral lenders do to make sure new funding ends up benefiting the citizens of debtor countries affected by the pandemic rather than lining the pockets of creditors? And how can they make debt restructuring more expedient? Here are three practical ideas:

More transparency on debt data and debt contracts

It is of utmost importance that the World Bank, the IMF, and the G20 continue to insist on strengthening the transparency of debt statistics.

A new and significant complication in assessing the external indebtedness of many developing economies involves China, which has become the largest bilateral creditor in recent years. Unfortunately, China’s lending is often shrouded in nondisclosure clauses, and a full picture is still elusive. More granular data on private sector creditor exposure may facilitate, in case of debt distress, more expedient creditor-debtor negotiations and allow both creditors and governments to identify which bonds are at risk of holdout or litigation tactics. An encompassing transparency initiative would include, for instance, full disclosure on sovereign bond ownership as well as credit default swaps that shift lender composition overnight. Knowing the players involved and the amounts owed would allow the international community and the citizenry of affected countries to better monitor how scarce resources in a time of crisis are being deployed. The accounts for the country itself must become more comprehensive, with improved data on domestic debt and debt owed by state-owned enterprises. Accounting for pension burdens is also increasingly important, as recent debt workouts in Detroit and Puerto Rico vividly illustrate.

Realistic economic forecasts that incorporate downside risks

Realistic growth forecasts are critical to avoid underestimating a country’s near-term financing needs and overestimating its capacity to service its debt commitments. IMF historian James Boughton notes that during much of the 1980s debt crisis, overoptimistic growth expectations persisted, especially in Latin America. Realistic forecasts, particularly recognizing the fragility of highly indebted countries, can speed resolution of any crisis. Earlier detection of insolvency and identification of cases in which large write-downs are necessary cannot guarantee a faster resolution but are a step in that direction.

New legislation to support orderly sovereign debt restructurings

Legal steps in jurisdictions that govern international bonds (importantly but not exclusively New York and London) or where payments are processed can contribute to more orderly restructuring by promoting a more level playing field between sovereign debtors and creditors. For instance, national legislation can cap the amounts that may be reclaimed from defaulted government bonds bought at a deep discount. In 2010, the United Kingdom enacted such a law for countries taking part in the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) debt relief initiative, while Belgium in 2015 passed the so-called Anti–Vulture Funds Law, which prevents litigious creditors from disrupting payments made via Euroclear. It would also energize legislation to facilitate a majority restructurings, which would allow a sovereign and a qualified majority of creditors to reach an agreement binding on all creditors subject to the restructurings.

The global pandemic is a once-in-a-century shock that merits a generous response from official and private creditors toward emerging market and developing economies, including preserving the global trading system and helping countries weather debt problems.

Support must be forthcoming, regardless of what progress can be made in better managing debt workouts. However, to make sure as much aid as possible gets through to debtor country citizens, it is essential to ensure inter-creditor equity and fair burden sharing, especially between official and private creditors. The more official aid and soft loans can go toward helping needy citizens around the globe—and the less such assistance ends up as debt repayments to uncompromising creditors—the better.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Bulow, Jeremy, and Kenneth Rogoff. 1989. “A Constant Recontracting Model of Sovereign Debt.” Journal of Political Economy 97 (February): 155–78.

———, and Afonso Bevilaqua. 1992. “Official Creditor Seniority and Burden Sharing in the Former Soviet Bloc.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1, 195–222. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth Rogoff. 2009. This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schlegl, Matthias, Christoph Trebesch, and Mark L. J. Wright. 2019. “The Seniority Structure of Sovereign Debt.” NBER Working Paper 25793, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Zettelmeyer, Jeromin, Christoph Trebesch, and Mitu Gulati. 2013. “The Greek Debt Restructuring: An Autopsy,” Economic Policy 28 (75), 513–63.