Nowcasting and new data sources can provide timelier and more frequent indicators

Thierry Kalisa started working with new data for real-time economic projections, or “nowcasting,” a decade ago, but the pandemic brought its potential into sharper focus.

As a Rwandan finance ministry official when COVID hit Kigali, the capital, he teamed up with a joint task force with the central bank to monitor a shuttering economy under sub-Saharan Africa’s first lockdown. Official economic indicators would soon be outdated, even before publication.

The group launched a weekly economic activity index based on a central bank measure incorporating factors like exports, imports, and real-time consumer spending captured from the tax authority’s electronic billing machines in stores. The outlook deteriorated. The economy would soon contract.

“This helped the government revise growth projections, adjust the macro framework, and take timely policy actions,” said Kalisa, who joined the central bank as chief economist in 2021.

The National Bank of Rwanda today includes nowcasting in staff briefings before quarterly Monetary Policy Committee meetings, and Kalisa’s staff of economists, statisticians, and data scientists is expanding to help deliver. “This is very demanding in terms of analytical capacity, but is also producing high-frequency indicators,” he said.

Data gaps

Rwanda is among developing economies taking a new approach to economic measurement. Many aim to narrow gaps with advanced economies and most emerging markets in official indicators many developing economies publish infrequently or with a delay. Those advanced and emerging market economies have the staff, funding, and other necessary resources. Large populations in developing economies, however, are left out.

Initiatives include real-time trackers of economic growth, inflation, trade, and consumption. Several low-income countries are building out data operations with support from IMF capacity development and technical assistance (see sidebar).

Data gaps affect low-income countries disproportionately. Advanced economies and most emerging markets publish GDP quarterly. But about a third of countries in the world have only annual GDP, leaving policymakers in the dark for long periods.

And GDP, even for the countries that publish it quickly, still comes out a month or more after the end of the quarter. During crises, the wait bedevils policymakers, who must steer the economy without knowing which way it’s heading.

The unprecedented disruption of the pandemic drove this reality home and pointed to the need for more timely and frequent measures to complement official data. Some activities ceased, others exploded, and indicator data collection suffered, causing distortions. Bruno Tissot, head of statistics at the Bank for International Settlements and secretary of its Irving Fisher Committee on Central Bank Statistics, calls it “statistical darkness.”

“Central banks around the world have recognized the primacy of providing timely indicators, for instance by mobilizing alternative high-frequency data sources, constructing weekly or even daily indicators, and enhancing their nowcasting exercises,” the committee observed in a 2023 report on postpandemic central bank statistics.

Forecasting tool

Nowcasting originated in the 1980s as a meteorological term for predicting conditions just a few hours ahead. It means something else in the world of economics.

“With the weather, you look outside of your window, you see whether it’s raining or not,” said Domenico Giannone, a nowcasting pioneer. “In economics, you need to wait.”

Giannone’s 2008 paper on nowcasting, coauthored with Lucrezia Reichlin and David Small, is credited with introducing the term to economics.

Giannone and Reichlin, then at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, began developing a model for short-term forecasting in 2002, in response to a request from Ben Bernanke, one of the Federal Reserve governors at the time. He asked them to explore the feasibility of a comprehensive big data model for forecasting and policy analysis, covering interactions among key sectors of the economy. Giannone and Reichlin discovered that prediction was possible only for the present, very recent past, and very near future—what they labeled “nowcasting”—and built a model to use real-time data to do so. It put what was previously informal, and based largely on judgment, into a formal statistical framework.

“The Fed was interested in seeing whether that kind of framework could be adapted to the problem of reading all the different releases in real time,” recalled Reichlin, a professor at the London Business School and former research director at the European Central Bank (ECB). “At the time, macroeconomic models were relatively small—it was before ‘big data’—and we started thinking, What models could handle a lot of time series and at the same time retain some simplicity so as not to generate volatile and unreliable estimates?”

Giannone later built on that work at the New York Fed, where he led development of a nowcast of weekly estimates of quarterly US economic growth.

After roles at the ECB, Amazon, and the IMF, Giannone joined Johns Hopkins University this year to focus on improving economic activity measurement in low-income countries. He was motivated partly, he said, by the realization that nowcasting tools of larger, wealthier economies covered nearly the entire global economy, but low-income countries had almost nothing.

Flying blind

Low-income countries face challenges with nowcasting and with the official data it complements, especially when government budgets are strained and skilled staff scarce. But practitioners still see promise in sharpening real-time measures.

First estimates of GDP in many advanced economies come out about a month after the end of the quarter—two months in some major emerging market economies—then are revised. In developing economies it can take more than three months.

Kenya’s National Bureau of Statistics, for example, releases GDP about three months after a quarter ends, but the central bank uses nowcasting tools fine-tuned by IMF staff and Giannone to start gauging the quarter after only a week, using private consumer spending data, then remittance data available after two weeks. Trade, money supply, tourism, and electricity data available in about 40 days help refine the picture and give a good indication of the health of the quarter in half the usual time.

Loading component...

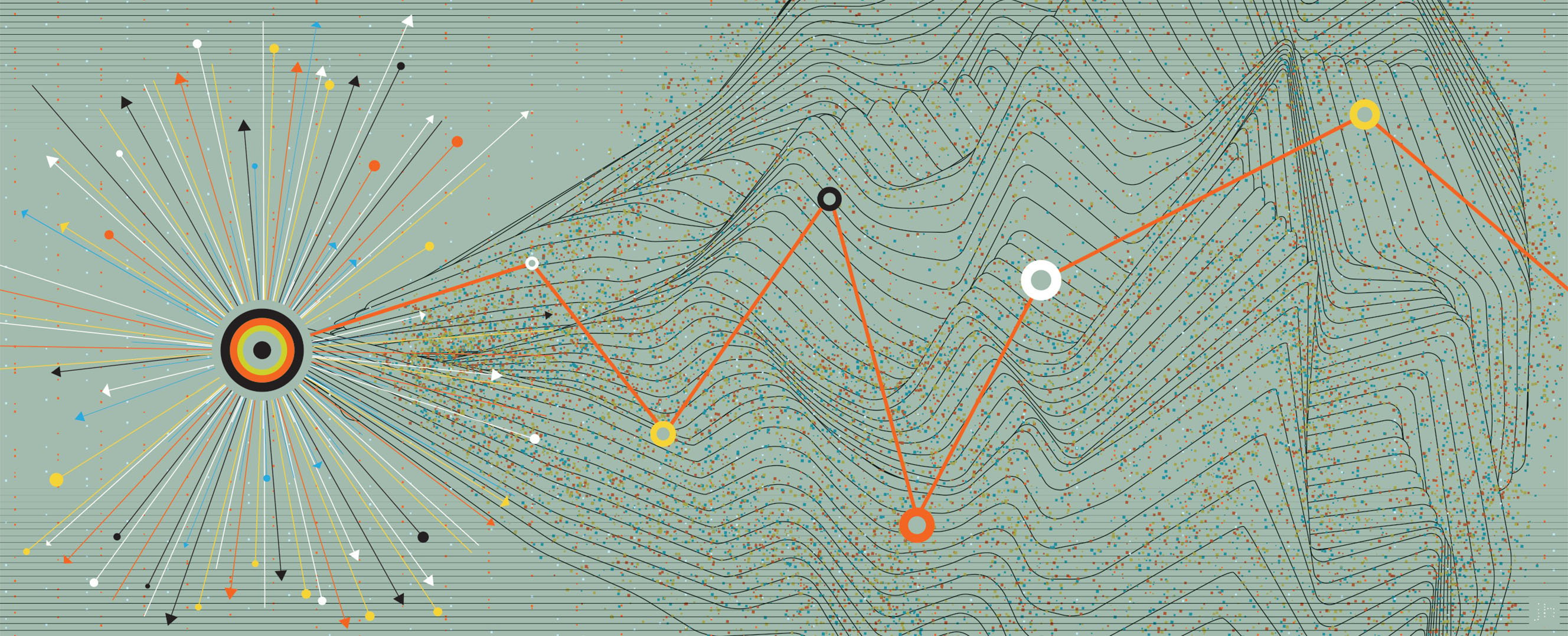

Signals and movement

In countries where data is sparse, as in low-income countries, transaction data like that incorporated into the Kenya model “will be extremely useful,” Giannone said, and much more informative than in advanced economies, where indicators are out almost daily.

His latest research focuses on global linkages and nowcasting of one country’s activity based on readings from neighbors, trade partners, and the global economy, using a model incorporating GDP for all countries.

“Every country has a global component and a regional component, and then from this we interpolate for countries that have less information, using countries that have more information,” he said, citing how neighbors and major trading partners can help show the direction of activity. “If you get GDP for the United States, this provides some signal also for Cambodia. There’s a lot of comovement.”

Recent advances in large language models and artificial intelligence open remarkable new possibilities for exploiting text as data and for integrating data with metadata, he said.

Gauging expansions and contractions in real time holds even more promise, research he considers a priority. “To understand whether you are in a recession in a country where GDP is not available quarterly, you have to wait a year,” he said. “A policymaker doesn’t have a clear idea of where they are. So it’s extremely important to move in that direction.”

High-frequency sources

In South Africa, an emerging market economy and the continent’s largest, central bank researchers want greater understanding of economic signals from real-time data, including new sources that can help gauge the effects of disruptions. For example, the economy there faced an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease this year. Supply disruptions sent beef prices soaring, which contributed to the fastest overall year-over-year consumer price increase in 10 months.

South African Reserve Bank economists got an early read from commercial agricultural data for meat and other crops to gauge food inflation.

This underscores how nowcasting works in practice and why it’s valuable. Statistics South Africa released the consumer price index (CPI) for September three weeks after the end of the month, but corresponding commercial data for the month were available two weeks earlier.

The underlying data come from high-frequency sources like wholesale and retail sales, livestock auctions, and produce markets, which offer highly disaggregated reads on food components like meat, fruit, and vegetables, according to Mpho Rapapali, an economist in the Research Department who works on the measures. Statistical analysis shows that the commercial indicators lead CPI by one to three months across components, she said.

“That’s been very instrumental in helping us with our forecasts,” Rapapali said in an interview. “We can also have a weekly checkpoint to see what’s happening in these food categories.”

‘Start with the data’

Nowcasting models have become more sophisticated in recent years, and large language models allow access to more data than in the past. The novelty of promising new measurement tools may be irresistible, but there are caveats. Practitioners caution that there’s no shortcut to the toil of expanding official indicators or raising the frequency and granularity of existing gauges. New methods can help the effort, working in tandem to better inform policy, but can’t replace rigorous data collection.

Reichlin says sophisticated techniques usually aren’t the best place to start when countries have few resources. “The first thing is to try to see what high-quality data are produced in the country, or what proxy you can use if the hard data are not there,” she said. “First start with the data, then you get to the technique. That’s very important.” Simple models often perform best, and nowcasting is more about exploiting different data releases for a timely signal and combining series at different frequencies, she said.

New data also can be noisy or nonrepresentative, and models that work well can fail when the world changes, according to Joshua Blumenstock, who has advised countries in Africa and South Asia as codirector of the University of California, Berkeley, Global Opportunity Lab, which uses novel data and an interdisciplinary approach to guide policy. He said new data tools also come with broader concerns: privacy, transparency, legitimacy, and governance.

Developing economies also face capacity challenges. Central banks and governments may lack the budgets and ability to build out rosters of economists, statisticians, and data scientists and equip them with advanced computing tools.

New appreciation

Challenges aside, the direction for developing economies is toward more nowcasting to augment data where needed, as well as expanded official economic indicators.

Just as Kalisa, in Rwanda, is expanding his department, so is a counterpart on the other side of the globe. Samoa, one of the world’s least-populated countries, with just 220,000 people, is two years into a formal nowcasting system, supported by technical assistance from IMF staff. At the central bank, which has fewer than 90 staff members, Karras Lui, economics department manager, expects to expand his group from 8 people to 10.

“We’ll gradually get more resources as we continue to build our capacity for doing forecasting,” Lui said. “There’s now an appreciation from the board not only of these new tools, but the analysis we’re providing.”

DATA AND INNOVATION IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

Case studies of IMF capacity development show how better economic measurement and technological innovation can aid sound policymaking

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

Sharpening policy decisions

The Central Bank of the Congo is among those developing a forecasting and policy analysis system with assistance from the IMF that enhances economic analysis, supports more systematic decision-making, and improves communication with the public.

A central innovation within this system is nowcasting, which is crucial in a country where compiling reliable statistics remains difficult and official GDP figures are published only annually and with long delays. Timely information helps policymakers detect turning points in growth and calibrate policy responses more effectively. Policymakers also face challenges from high dollarization; the boom-bust cycle in the key mining sector, which contributes about a third of GDP; and the impact of exchange rates and commodity prices on inflation.

The central bank’s nowcast identifies real-time economic signals by combining traditional high-frequency indicators—such as copper and cobalt production and prices and money supply—with nontraditional inputs like satellite night-light intensity and Google search trends. The results feed into a quarterly projection model that links short-term assessments with medium-term forecasts and policy scenarios. Together, these tools are helping the central bank pursue forward-looking, transparent, and data-driven monetary policy.

GUINEA-BISSAU

Blockchain transparency

In 2020, Guinea-Bissau faced a daunting fiscal challenge: The public wage bill consumed about four-fifths of its tax revenues, one of the highest ratios in sub-Saharan Africa. Managing salaries and pensions for civil servants was opaque, error-prone, and vulnerable to abuse.

In May 2024, and in collaboration with the IMF, the consultancy EY, and donors, Guinea-Bissau became one of the first countries in the region to deploy blockchain technology to manage its public wage bill at the ministries of finance and public administration.

The secure platform creates a tamper-evident digital ledger of salaries and pensions across government agencies, flagging transaction discrepancies and enabling near real-time tracking of who is paid, how much, and whether payments are authorized. It reduces the burden of audits and provides policymakers with accurate, timely fiscal data—all while building a foundation for future AI-enabled tools.

The blockchain project is a useful tool that supports several reforms aimed at controlling wage spending introduced as part of an IMF-supported program. The results are promising: The wage bill fell to half of tax revenue in 2024, a substantial improvement but still above the regional benchmarks. The platform will be expanded to cover all 26,600 public officials and 8,100 pensioners nationwide.

KENYA

Real-time insights

Among its peers, Kenya has relatively high-quality macroeconomic data. However, its official quarterly GDP estimates usually come with a lag of at least three months, and some other higher-frequency indicators of economic activity are also published with delays. In this context, building nowcasting models around available data could give policymakers a quick read of economic activity ahead of the official GDP releases.

Ongoing work at the IMF on nowcasting finds that it is possible to approximate Kenya’s economic growth to a large extent ahead of the official GDP releases by exploiting comovement in a range of indicators (economic, financial, and others) through business cycles. The Central Bank of Kenya, supported by IMF technical assistance, has also been exploring ways to inform its view on economic growth by using nowcasting techniques and extracting information content of its bimonthly surveys.

Nowcasts, fine-tuned with advancement in data availability and computing technology, help economists, investors, and policymakers with a real-time gauge of economic performance. Finally, the IMF’s research also shows that nowcasting can be applied to countries where quarterly GDP estimates are unavailable.

MADAGASCAR

AI customs

Like many countries worldwide, Madagascar faces significant challenges in managing the complexity and volume of its international trade operations, particularly fraud detection in customs declarations.

Taxes on international trade are critical for government revenue. But while much of the customs process was already digitalized, automating some components, particularly fraud risk analysis, remained elusive, in part because of limited data and limited methods to analyze unstructured and textual information.

Customs officials in October introduced agentic AI, an autonomous decision-making form of artificial intelligence, to detect inconsistencies that signal fraud by cross-analyzing customs declarations, invoices, manifests, and external and internal databases. This automated many manual frontline inspectors’ tasks, allowing experts to focus on complex cases.

The initiative, supported by IMF technical assistance and capacity development and building on earlier support from the Korea Customs Service, advanced technological capabilities while allowing the customs administration to own and further develop AI tools. The work underscores how new technologies can strengthen customs integrity and efficiency—and modernize trade controls.

SOURCE: IMF staff.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

Reference:

Giannone, D., L. Reichlin, and D. Small. 2008. “Nowcasting: The Real-Time Informational Content of Macroeconomic Data.” Journal of Monetary Economics 55 (4): 665–76.