Material demands—for energy, chips, and minerals—will determine who dominates data

Artificial intelligence is often cast as intangible, a technology that lives in the cloud and thinks in code. The reality is more grounded. Behind every chatbot or image generator lie servers that draw electricity, cooling systems that consume water, chips that rely on fragile supply chains, and minerals dug from the earth.

That physical backbone is rapidly expanding. Data centers are multiplying in number and in size. The largest ones, “hyperscale” centers, have power needs in the tens of megawatts, at the scale of a small city. Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Meta already run hundreds worldwide, but the next wave is far larger, with projects at gigawatt scale. In Abu Dhabi, OpenAI and its partners are planning a 5-gigawatt campus, matching the output of five nuclear reactors and sprawling across 10 square miles.

Economists debate when, if ever, these vast investments will pay off in productivity gains. Even so, governments are treating AI as the new frontier of industrial policy, with initiatives on a scale once reserved for aerospace or nuclear power. The United Arab Emirates appointed the world’s first minister for artificial intelligence in 2017. France has pledged more than €100 billion in AI spending. And in the two countries at the forefront of AI, the race is increasingly geopolitical: The United States has wielded export controls on advanced chips, while China has responded with curbs on sales of key minerals.

The contest in algorithms is just as much a competition for energy, land, water, semiconductors, and minerals. Supplies of electricity and chips will determine how fast the AI revolution moves and which countries and companies will control it.

A hungry industry

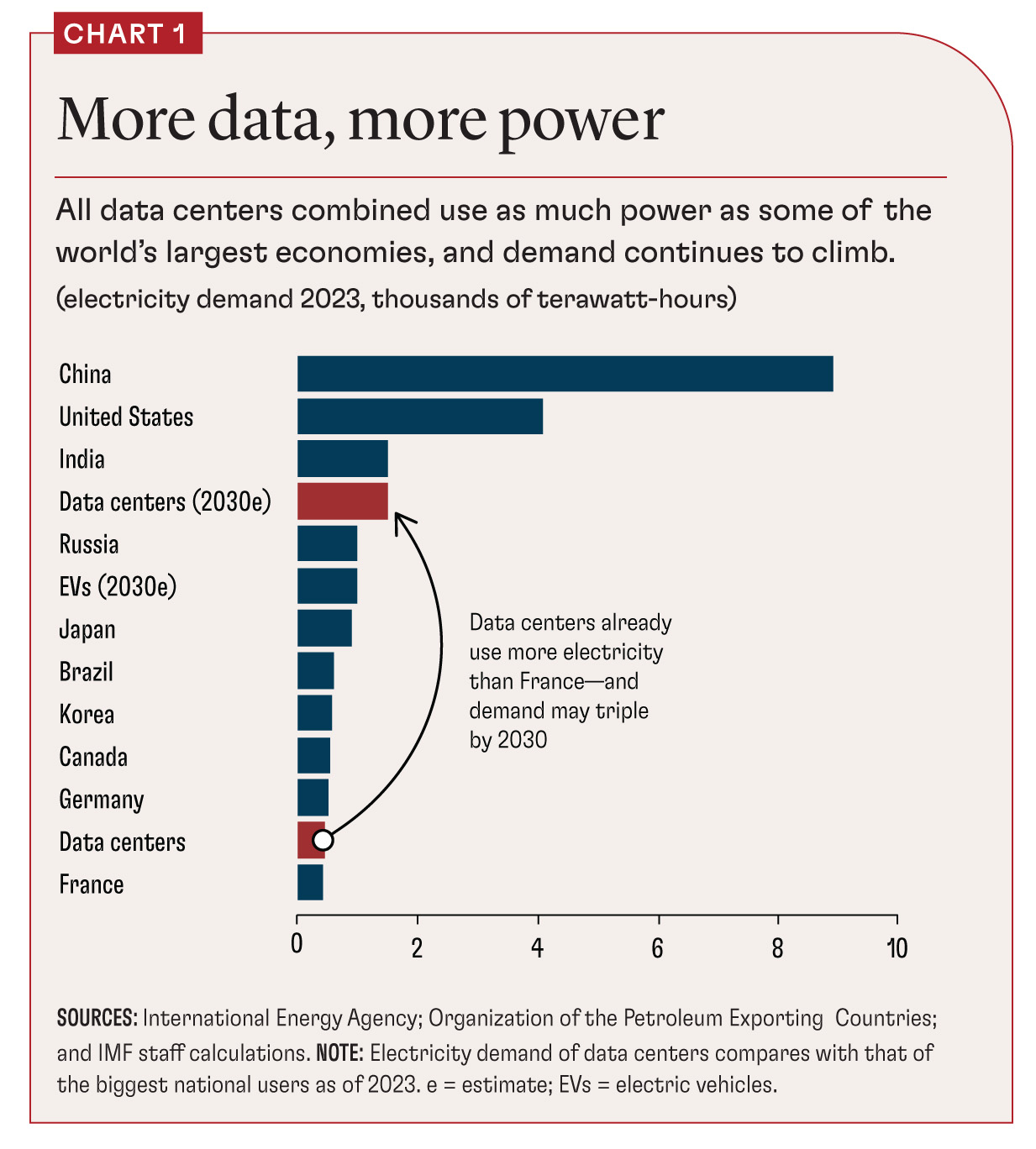

Artificial intelligence is devouring electricity. Data centers already use about 1.5 percent of global electricity supply, roughly the same as the United Kingdom. Only a portion of that demand comes from AI, but it is growing fast. Training an advanced model can consume as much power as thousands of households use in a year, and running it at scale multiplies the burden. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects data center demand to more than double by 2030, with AI responsible for much of the increase.

Globally this surge is manageable: AI accounts for less than a tenth of added power demand this decade, far below that of electric vehicles or air-conditioning. But national balances tell a different story. In the US and Japan, data centers could account for nearly half of new demand by 2030. In Ireland, they already use more than a fifth of the country’s electricity, the highest share among advanced economies.

The local strains are sharper still. Unlike steel plants or mines, data centers cluster near big cities, can be built in months rather than years, and keep getting bigger. This combination makes them uniquely disruptive to local grids.

In northern Virginia, the world’s largest data hub, data centers already consume about one-quarter of the state’s power, forcing utilities to delay or cancel other connections. Rising electricity bills became a flash point in the state’s governor’s race. In Ireland, Dublin’s grid operator froze new projects in 2022, approving only those that could generate their own power. Singapore halted approvals altogether in 2019 and now allows facilities only under strict efficiency rules.

Big Tech turns to power

Technology companies are becoming power players themselves. The largest firms are now among the world’s biggest corporate buyers of renewable energy. Microsoft, Amazon, and Google have each signed multibillion-dollar power purchase agreements that rival those of traditional utilities. Their decisions about where to site data centers increasingly shape which solar and wind projects get built.

Some are adding on-site generation at data centers to cut reliance on the grid, or are betting directly on new technologies. Microsoft has explored nuclear, from small modular reactors to possible acquisitions of mothballed plants such as Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. Google is backing advanced geothermal. Amazon is testing hydrogen for backup power. With President Donald Trump rolling back many of President Joe Biden’s climate policies, the AI power race has unexpectedly cast Big Tech as a lifeline for clean-energy investment.

Over time, Big Tech’s capital could help accelerate innovation in clean power, but it could also cement dependence on fossil fuels. While AI has boosted renewables in Europe, demand in the US—home to more than 40 percent of the world’s data centers—still leans heavily on natural gas, adding to emissions.

Smarter machines

Artificial intelligence is not only a voracious consumer of electricity, it can also help manage it, balancing power grids, forecasting renewable output, and optimizing energy use in buildings and industry. Some cities are even piping waste heat from server farms into district heating networks. These applications will not erase the sector’s footprint, but they can soften the strain.

Efficiency is improving too. New generations of chips, such as Nvidia’s Blackwell processors and Google’s tensor processing units (TPUs), are designed to deliver more operations per watt. On the software side, China’s DeepSeek, released in January 2025, was trained at a fraction of the cost and energy of what OpenAI and Google spent on comparably sized models.

Yet efficiency brings its own paradox. History suggests that cheaper computing power sparks more use, an effect known as the Jevons paradox. AI may indeed deliver smarter, leaner models, but the appetite for applications is likely to grow even faster.

If electricity is AI’s first constraint, semiconductors are the second. Training state-of-the-art models requires thousands of specialized chips, most designed by Nvidia and manufactured almost exclusively in Taiwan Province of China by the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). That concentration has made chips the single most strategic choke point in the AI supply chain.

The geopolitical stakes are already clear. The US has restricted advanced chip exports to China while subsidizing domestic fabrication plants. Far from stifling progress in China, those curbs may have pushed its companies to innovate around them, as DeepSeek has shown. Beijing is racing to build its own domestic champions. Europe, Japan, and India are pouring billions into their own industries. Access to chips is now a litmus test of technological sovereignty.

Loading component...

Mineral footprint

Chip fabrication itself is resource-hungry. A single cutting-edge fabrication plant can consume as much electricity as a small city and require vast amounts of ultrapure water. But the deeper story lies farther upstream, in the minerals that make advanced chips and data centers possible.

They need gallium and germanium for advanced circuitry, silicon for chips, rare earths for cooling fans, copper for the cabling that binds servers together. A single hyperscale campus can contain nearly as much copper as a midsize mine produces in a year.

By 2030, data centers could be consuming more than half a million metric tons of copper and 75,000 tons of silicon each year—enough to lift their share of global demand to 2 percent, according to the IEA. For gallium, the leap is sharper still: Data centers could account for more than a tenth of total demand. Those percentages may sound modest, but they come on top of surging requirements from electric vehicles, wind turbines, and defense industries, all chasing the same finite supply.

That supply is highly concentrated. China controls 80–90 percent of global refining of silicon, gallium, and rare earths. In 2023 it restricted exports of gallium and germanium; since late 2024 new curbs have followed on tungsten, tellurium, bismuth, indium, and molybdenum. All are critical inputs for microprocessors, diodes, and server hardware. Prices for many of these metals have spiked. Washington, Brussels, Tokyo, and Seoul have responded with critical-mineral strategies, from recycling programs to alliances with resource-rich countries in Africa and Latin America.

The scramble for minerals, as for chips, leads to concentrated supply chains and high barriers to entry, with clear geopolitical stakes. Securing stable, sustainable access will shape who can truly harness the AI revolution.

Land and water

Hyperscale data centers thrive where cheap power, abundant water, and fast fiber-optic links converge. Land is seldom the limiting factor. These sites are vast by urban standards but modest compared with farming or mining acreage. Even so, their arrival can still reshape local economies as farmland in northern Virginia or Oregon is concreted over by endless rows of server halls.

Water is more contentious. Cooling demands millions of gallons a day, and two-thirds of new US centers since 2022 have been built in water-stressed regions, Bloomberg News reports. In Arizona, projects have sparked fights over whether scarce water supplies should go to households or to Big Tech. Similar disputes are emerging in Spain and Singapore. Yet most of AI’s water footprint is indirect. Power plants that supply data centers consume far more water than the centers themselves.

Climate and minimizing network delays also shape siting decisions. Ireland’s dense cluster reflects its role as a transatlantic cable hub. Abu Dhabi’s planned 5-gigawatt campus was chosen partly to minimize delays with Asia and Europe. And colder countries, from Norway to Iceland, tout their climate advantage: less energy needed for cooling.

The result is a patchwork geography: Some governments impose curbs to protect grids and water; others vie to host projects with cheap renewables, district heating, or simply space to build. This is another reminder of how material constraints will shape the future of AI.

Policy challenges

The resource demands of AI force governments to treat power plants, grids, water, and minerals as an integral part of their digital policies.

One challenge is knowing what to plan for. Forecasts of data center demand diverge widely: For 2030, the highest published estimate is nearly seven times the lowest. Yet the pace of building leaves little time for certainty. Governments must expand electricity systems fast enough to keep up, but without overbuilding or locking in fossil fuels.

Another gap is transparency. Even in an information age, there is little public reporting from the industry on data center use of electricity, water, or minerals. Greater disclosure would give regulators, utilities, and communities a clearer picture of what is coming.

Finally, sustainability and equity. Expanding grids and supply chains without environmental and social safeguards risks repeating the boom-and-bust cycles of past commodity races. And the benefits of the AI boom will be tilted toward the rich world if developing economies remain just suppliers of raw materials and face higher implied costs for energy and capital.

If managed well, the AI boom could accelerate clean energy and foster more resilient supply chains. If not, it risks locking in new emissions and deepening resource dependence.

This is not just a digital contest. It’s a material one—over electrons, gallons, wafers, and ores. How governments and companies handle those foundations will decide not only who leads in AI, but how sustainable and widely shared its gains will be.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

Reference:

International Energy Agency (IEA). 2025. Energy and AI. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and IEA.