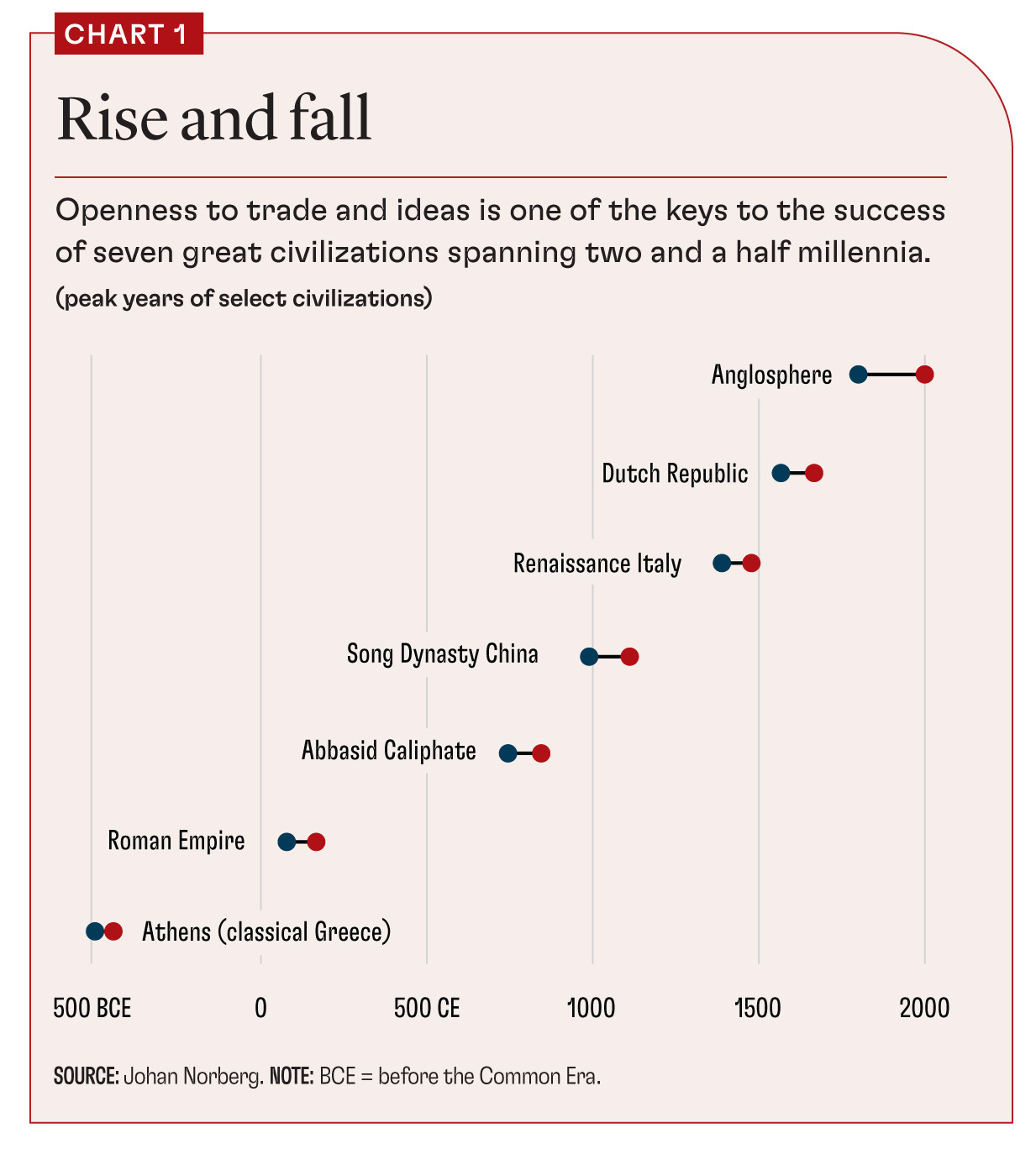

From Athens to the Abbasids to today’s Anglosphere, creativity and commerce drive greatness

Ninth century Baghdad, seat of the Abbasid Caliphate, was designed as a perfect circle to honor the Greek geometer Euclid. The empire, enriched by trade in goods and ideas, sponsored an ambitious translation movement to collect the accumulated knowledge of the many cultures it interacted with.

This open mindset is one of the keys to the success of seven great civilizations spanning two and a half millennia. The practical lessons of these cultures could not be more important today as countries choose once again to wall themselves off—physically, economically, digitally, and from new ideas.

Leaders promise safety, greatness, and a return to an imagined golden age through protection and control. It is a familiar and tempting story when the future feels uncertain. Yet history tells a different tale.

The most secure and prosperous societies did not hide from the world. They were confident enough to remain open to trade and ideas, allowing the new to challenge the known. Progress emerges when people experiment, borrow, and combine ideas in ways no planner could ever foresee; decline happens when fear overcomes curiosity.

These are among the central lessons of history’s real golden ages that I explore in my new book, Peak Human: What We Can Learn from the Rise and Fall of Golden Ages.

Secrets of the seven

While very different, the cultures studied—from ancient Athens to the modern Anglosphere—had some striking commonalities. They all fostered periods of intense innovation, excelling in cultural creativity, scientific discovery, technological progress, and economic growth.

Admittedly, they were not golden for everyone. All practiced slavery and denied women most rights until very recently. The classicist Mary Beard has observed that when her readers express envy for life in ancient Rome, they always seem to think they would have been senators there—a tiny elite of a few hundred men—rather than one of the millions of slaves.

But poverty and oppression have been the rule in human history. What made these seven cultures unique was that they nonetheless offered more freedom and progress, and better living standards for a larger share of their populations, than other civilizations of their time.

What were their secrets? Not geography, ethnicity, or religion. Creative and open cultures have popped up in the most unlikely places, sometimes with rough terrain and poor soil and lacking natural resources. A region that seemed peripheral in one era could become a leader in the next.

Open mindset

Great civilizations came in different flavors of pagan, Muslim, Confucian, Christian, or secular. What mattered was not the content of their creeds but that they didn’t harden into orthodoxy.

Greatness emerges when imitation leads to innovation. These civilizations didn’t invent all the breakthroughs that made them successful; instead, they borrowed or stole them from others. Athens learned from Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Phoenician cultures nearby, and from a thousand other Greek city-states. The Abbasids consciously built their capital, Baghdad, at what has been described as “the crossroads of the universe” to gain access to the goods, skills, and discoveries of others.

Openness to international trade exposed cultures to new habits and undermined the notion that there is only one right way, in religion, politics, art, or production. Maritime powers, in particular, ventured farther and saw more.

Renaissance Italian merchants picked up Arabic numerals and texts on their business journeys. British merchants venturing east found porcelain and textiles that would inspire domestic production.

The Romans absorbed methods and peoples through a kind of strategic tolerance of cultural differences that accompanied their brutal conquests, constantly acquiring better technologies and finding new talent for their legions and even the Senate. Like the United States today, the Dutch Republic drew a constant influx of new energy and talent by opening its doors to immigrants from other cultures, from the artisans who developed the textile industry to the dissidents who kick-started the Enlightenment.

Rebellious innovation

But imitation can take you only so far. To make progress self-sustaining, imported influences had to combine with local ideas and practices in ways that produced transformative innovations—from better crops and iron tools to groundbreaking art and financial instruments.

To bring something new into the world, people must be allowed to experiment with, and exchange, theories, methods, and technologies, even when it makes elites or majorities uncomfortable. Every major innovation, argues Nobel Prize–winning economic historian Joel Mokyr, is “an act of rebellion against conventional wisdom and vested interests.”

At a certain point, progress became self-reinforcing, as it reshaped how these cultures saw themselves. When new influences and combinations improved living standards and spread more widely, they sometimes generated a culture of constant, self-renewing creativity—a culture of optimism. That proved decisive.

But as long as conventional wisdom and vested interests hold veto power, not much happens.

In these creative cultures, they rarely did. Athens had its direct democracy, where every free man had a voice and a vote in the assembly. The Italian city-states and Dutch Republic were governed by the wealthy, but power was dispersed, and there were mechanisms to check arbitrary rule. Some form of division of power has always been essential to protect liberty and innovation, as the US founders learned by studying the ancients.

The rulers of the Roman Empire, the Abbasid Caliphate, and Song China held power over life and death. Yet even they were constrained by legal systems and individual rights they were expected to respect—though reminding the emperor of that could be risky, and best done only when he was in a particularly good mood.

Rewarding climate

Innovation is difficult, and success is never guaranteed. Progress, therefore, depends on a hopeful cultural climate: a belief that trying something new might be worth it, that it might work, and that you might be richly rewarded if it does—as was true during the Renaissance, the Industrial Revolution, and today.

In addition to patrons and patents, you need role models: people who show that the impossible can be done, to inspire, teach, and challenge. That’s why creativity tends to cluster, from philosophers in Athens and artists in Renaissance Italy to tech pioneers in Silicon Valley.

In Renaissance Florence, Michelangelo mocked Leonardo da Vinci for being a procrastinator who never finished most of his works. Leonardo, meanwhile, thought Michelangelo’s overly muscular figures looked more like sacks of walnuts than real humans. They both had a point—and rivalry pushed them to create even more impressive works.

Pessimism—the sense that everything is hopeless and that effort is futile—is self-fulfilling. And that is the key to understanding why golden ages eventually lose their luster and decline.

Loading component...

Signs of sickness

Over time, the vested interests Mokyr called out often regain their footing and strike back. Political, economic, and intellectual elites build their power on certain ideas, classes, and modes of production. When these change too quickly, the powerful have an interest in stepping on the brakes.

As civilizations decline, elites who once benefited from innovation try to pull the ladder up behind them. Roman emperors seized power from locally governed provinces, and the elected leaders of Renaissance republics eventually made their positions hereditary.

Divided societies were less able to resist aggressive neighbors who tried to kill the goose that laid the golden eggs.

Outsiders can kill and destroy people and buildings, but they cannot kill curiosity and creativity. We can do that only to ourselves. When we feel threatened, we long for stability and predictability, shutting out what seems strange or uncertain.

Every great civilization experienced its own death of Socrates moment. Often in the wake of pandemics, natural disasters, or military conflicts, societies turned away from intellectual exchange, cracking down on eccentric thinkers and minorities. People began to rally behind strongmen who imposed controls on their economies and abandoned international openness.

In the crisis-ridden late Roman Empire, pagans began persecuting Christians, and soon after, Christians persecuted pagans. As the Abbasid Caliphate fragmented, its rulers forged a repressive alliance between state and religion. The Renaissance ended when embattled Protestants and Counter-Reformation Catholics each built their own church-state alliances to suppress dissenters and scientists. Scholars became cautious, literature introspective, and art backward-looking.

Not even the tolerant Dutch Republic escaped. In 1672, when the country was attacked by France and England simultaneously, a desperate population handed power to an authoritarian stadtholder and lynched the former leader who had contributed most to their golden age, Johan de Witt. Calvinist hard-liners took control and purged Enlightenment thinkers from their once-vibrant universities.

Closure and collapse

Hard times create strongmen—and strongmen create harder times.

As freedom of expression gave way to orthodoxy, free markets were replaced by economic controls. When states struggled to raise revenue, they undermined property rights and market exchange to seize what they could.

Roman, Abbasid, and Chinese rulers all tried to solve social problems by refeudalizing their economies. Peasants were tied to the land, and commercial relationships were replaced by commands. Spending more than they collected was a common sign of states’ decline. They borrowed excessively and debased their coins, triggering inflation and financial chaos.

Often they abandoned the international trade that had brought them wealth and sparked creativity. Sometimes commerce collapsed because wars made roads and sea-lanes unsafe, as in Rome and during the late Renaissance. In a reaction against the openness of Song China, the subsequent Ming dynasty banned foreign trade altogether, and the militarization of the Roman and Abbasid economies extinguished commerce.

Such reactions reduced their ability to adapt locally to changing circumstances. Severed trade routes eroded economic and technological capacity, and new orthodoxies choked off the flow of ideas and solutions that might have helped them manage the crisis. They lost that spirit of curiosity that had once made them great.

Studying history can make us feel hopeful, but it is also humbling. Remarkable progress can appear unexpectedly in places with the right institutions, but it takes hard work to sustain them long term.

The ancient Greek historian Thucydides identified two opposite mindsets: that of Athenians, eager to venture out into the world to acquire something new, and that of Spartans, shutting out the world to preserve what they already had. Only the first mentality is consistent with constant learning, innovation, and growth. Every civilization, and probably every human being, is a little bit Athenian and a little bit Spartan—but it’s up to us to choose which one prevails.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.