IMF Spring Meetings Update | April 11, 2023

In our daily recap for Tuesday, April 11, we focus on the global economy’s rocky recovery, financial stability risks and how to manage them, capital flows and emerging markets, climate finance and energy security, and much more.

Global Recovery Endures but Road Is Getting Rocky

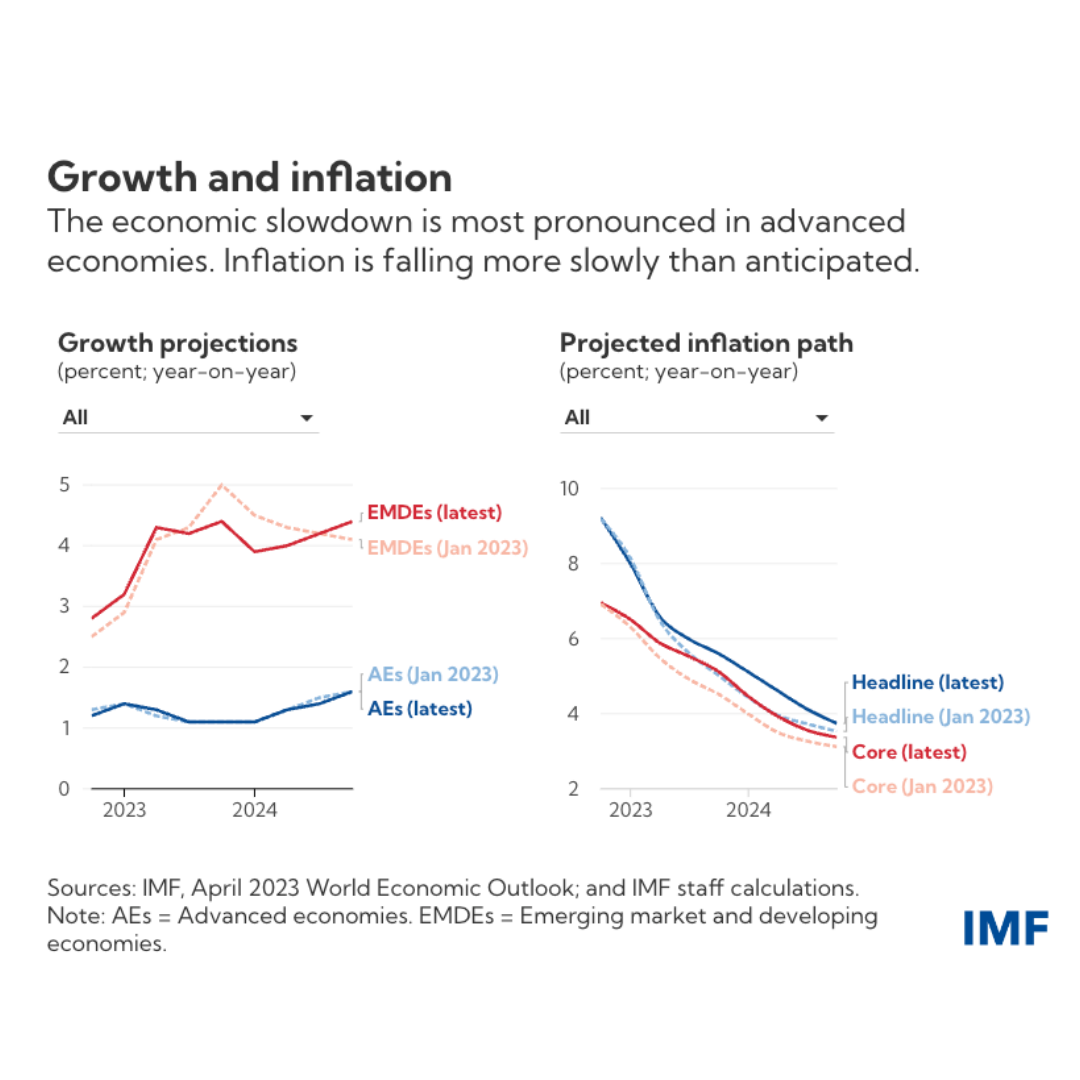

The global economy’s gradual recovery remains on track and growth will bottom out this year before rising slightly next year, the IMF’s Chief Economist Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas said at a press briefing on the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook. Growth this year would be 2.8 percent before rising modestly to 3 percent next year—0.1 percentage points below January’s projections. Global inflation will fall, though more slowly than initially anticipated, from 8.7 percent last year to 7 percent this year and 4.9 percent in 2024, he added.

Gourinchas said brief instability in the United Kingdom’s Gilt market and banking turbulence in the United States illustrated significant vulnerabilities and warned that the financial sector could be tested again. A sharp tightening of global financial conditions—sometimes called a risk-off event—would have a dramatic impact, in emerging market and developing economies especially. In such a severe downside scenario, global growth could fall to about 1 percent this year, Gourinchas said.

CHART of the Day

This year’s economic slowdown is concentrated in advanced economies, especially the euro area and the United Kingdom, where growth is expected to fall to 0.8 percent and -0.3 percent respectively. By contrast, many emerging market and developing economies are picking up, with year-end to year-end growth accelerating to 4.5 percent from 2.8 percent in 2022.

Learn more

Global Financial System Tested by Higher Inflation and Interest Rates

Rapid monetary policy tightening after years of low rates is exposing fault lines, said Tobias Adrian, the IMF’s financial counselor during a press briefing of the IMF’s latest Global Financial Stability Report.

The failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in the United States and the government supported acquisition of Switzerland’s Credit Suisse by rival UBS have rocked market confidence and triggered significant emergency responses by authorities, Risks to bank and nonbank financial intermediaries have increased as interest rates have been rapidly raised to contain inflation. Adrian said that interest rate rises can trigger banking sector vulnerabilities, but policymakers have the tools to contain these risks. Indeed, central banks have some instruments for fighting inflation and others for ensuring financial sector stability. Ideally, stability concerns are addressed through targeted tools, while monetary policy continues to address inflation.

Quote of the Day

My question today is what about the countries that are ready [for climate finance], what are we doing to make sure they become an example of what can be done. My country is one such country.

KAMPETA SAYINZOGA, RWANDA DEVELOPMENT BANK

Climate Finance and Energy Security

The world is putting about $1.3 trillion a year into clean energy. But to limit the global temperature increase to 1.5 °C, that number needs to triple. At a seminar, a panel discussed climate finance challenges and the solutions needed to close the gap. Energy expert Daniel Yergin outlined the complexities of the energy transition and stressed the importance of ensuring energy security. Tim Gould of the International Energy Agency explained the importance of the role of climate financing in transitioning to clean energy, which typically has lower operational but higher upfront costs. Rwanda’s Kampeta Sayinzoga and Egypt’s Rania Al-Mashat highlighted the major difficulties their countries face in securing financing and the need for international collaboration. IMF Deputy Managing Director Bo Li underscored the important steps the Fund is taking through the Resilience and Sustainability Trust and by working with multilateral development banks, bilateral donors and private investors to ensure its macro financing complements project financing from others.

Governor Talks: the Philippines

Central bankers must use all available tools in the fight against inflation including interest rates, regulation and maintaining a strong buffers of foreign-exchanges reserves, said the Philippines’ central bank chief during a Governor Talk. Felipe Medalla said that the Philippines and other emerging economies faced pressure on their currencies when the United States raised interest rates and they had to accept that the international financial system was driven largely by US domestic concerns. “We wish that the US was more caring about international conditions when they change policy rates.” Memories of the Asian financial crisis still influence attitudes towards risk in Asia’s banking sector today and this partly explained prudent management, he added. “Our banks are run by people who have very long memories of 1997—they hate mismatches.”

Number of the Day

2MILLION

An average living great whale is worth $2 million based on the value of its carbon sequestering services, ecotourism contribution, and other economic benefits, IMF economists Pat Escalante and Andras Komaromi said in an Analytical Corner presentation.

Learn more

Capital Flows From Emerging Markets

Capital outflows from emerging market economies over the past year totaled $300 billion. The reasons had little to do with country fundamentals, the IMF’s Andrés Fernández said during an Analytical Corner presentation. Two decades of data show that global factors account for as much as 60 percent of the variability in spreads, with the US monetary stance having the biggest effect, he said. Historically, emerging market bond spreads surge and the volume of capital flows drops a few months after a tightening of US monetary policy.

Photos

TULIPS BLOOM OUTSIDE THE IMF BUILDING.

IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva and First Deputy Managing Director Gita Gopinath speak with Mike Bloomberg at a reception.

IMF Financial Counselor Tobias Adrian answers questions after the Press conference.

Upcoming Events

Press Briefing: Fiscal Monitor

The launch of the IMF’s April 2023 #FiscalMonitor report “On the Path to Policy Normalization,” featuring the IMF’s Director of Fiscal Affairs Vitor Gaspar and economists Paolo Mauro, and Paulo Medas.

Event Details

Spending Well. Spending with Accountability

Addressing the challenge of spending well involves improving processes, transparency, and the enforcement of accountability to support strong public financial management, deliver better public services, and contribute to better fiscal outcomes.

Event Details

Third Ministerial Roundtable Discussion for Support to Ukraine

Co-chaired by the Government of Ukraine, the World Bank Group, and the International Monetary Fund.

Event Details