Keynote Address at the 46th SEACEN Governors Conference by Mr. Naoyuki Shinohara, Deputy Managing Director

February 25, 2011

As prepared for delivery

Your Excellency, President Mahinda Rajapaksa; our host Governor, Ajith Nivard Cabraal of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka; other SEACEN Governors; and distinguished invitees: it is my honor and pleasure to be with you here in Colombo at the 46th South East Asian Central Bank Governors’ Conference.

The theme of the conference—“Challenges to Emerging Economies’ Central Banks in the Post-Crisis Period”—couldn’t be more appropriate, and I very much look forward to the discussion ahead, which will surely be most useful for us all.

But before I begin, let me say a few words about the Sri Lankan economy. Just a couple of years ago, Sri Lanka faced a very difficult economic situation, in part due to the effects of the global economic and financial crisis. We at the IMF are pleased to have been able to support the strong recovery of the Sri Lankan economy, but much of the success is due to the leadership of the government. The recovery has also been helped by the end of a long period of civil conflict. To the Government of Sri Lanka I would like to offer my best wishes for continued success in its economic policies.

To help set the stage for today’s discussion, I would like to offer some observations on what the post-crisis period looks like—or at least how we at the IMF see it—focusing especially on what’s happening here in Asia. Some major themes that I will highlight are the likelihood of continued, substantial capital flows into many emerging markets, the risk of overheating in those economies, and the need to reorient them from exports toward domestic demand, as part of the global rebalancing that the world economy now faces. All of these developments, of course, have important implications for central banks as well as other macroeconomic policymakers, not to mention the IMF itself as it works in support of a multilateral approach to policies.

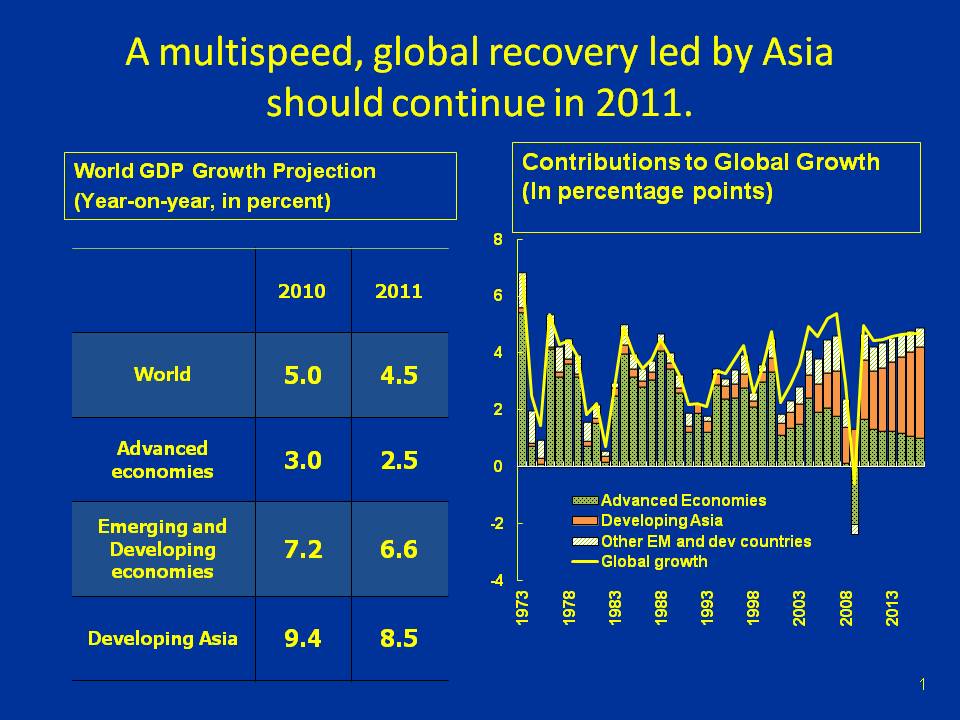

Chart 1

Let me start by observing that the global economy grew at a solid 5 percent in 2010 and is expected to continue recovering robustly in 2011, growing at 4½ percent overall, but with substantial variation across countries (left table, Chart 1). In this multispeed recovery, we expect to see advanced economies growing at what, given the depth of the recession, must be viewed as a sluggish rate of 2½ percent in 2011—and this is after an upward revision to our forecast in light of a recent fiscal package passed in the United States. We expect activity in the advanced economies to be weighed down by high unemployment rates, weak housing markets, financial systems that are still neither willing nor able to extend credit as they used to, and a modest drag from the sovereign debt crisis, including some additional financial strains and some induced fiscal austerity measures.

Emerging markets, by contrast, have not suffered these problems as acutely, and are instead benefiting from world trade, which grew sharply in 2010, and now faces a somewhat more challenging, but still positive, outlook. Earlier, they also benefited from the rebuilding of inventories. Emerging markets are expected to grow at a healthy rate of 6½ percent in 2011, but inflation pressures are mounting, and there are now signs of overheating, in part driven by strong capital inflows.

It is also worth noting that, for the first time, the global recovery is being led by Asia. Developing Asia will see its growth remain as high as 8½ percent this year—from nearly 9½ percent in 2010—and the region should contribute the lion’s share of global growth over the next few years (right, Chart 1). The ongoing—albeit subdued—recovery in advanced economies should support growth in Asia’s exports. But Asia’s domestic demand should also remain robust as tight capacity utilization and ample credit fuel investment, while strong labor markets and high equity valuations will support consumers’ income and confidence.

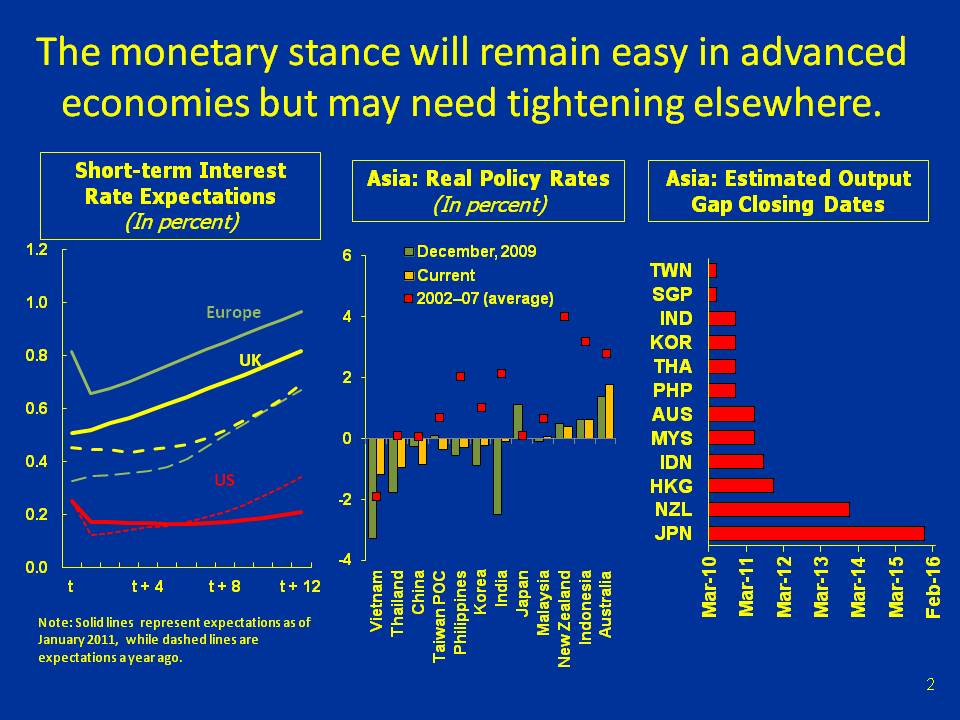

Chart 2

Corresponding to these very different growth circumstances, monetary policy requirements are also very different across the globe. With economic activity sluggish, and likely to remain so for a while in the advanced economies, it is little surprise that markets continue to expect policy rates in those countries to remain low for an extended time (left, Chart 2). Expected rates in the U.K. and the Euro area have risen over the past year, but they remain low by any standard, and in the U.S., they have dropped, reflecting the Fed’s communications and the launching of the second phase of quantitative easing (“QE2”).

In emerging markets, however, we expect a closing of most output gaps during 2010 or 2011—i.e., the emergence of supply constraints—as a result of rapid growth (right, Chart 2). Although several countries have started taking steps to normalize monetary policy stances, they remain generally accommodative, with real policy rates still negative or far below historical averages in many regional economies (center, Chart 2). It thus seems appropriate that monetary tightening should be on the cards.

Let me turn now to risks around the baseline outlook.

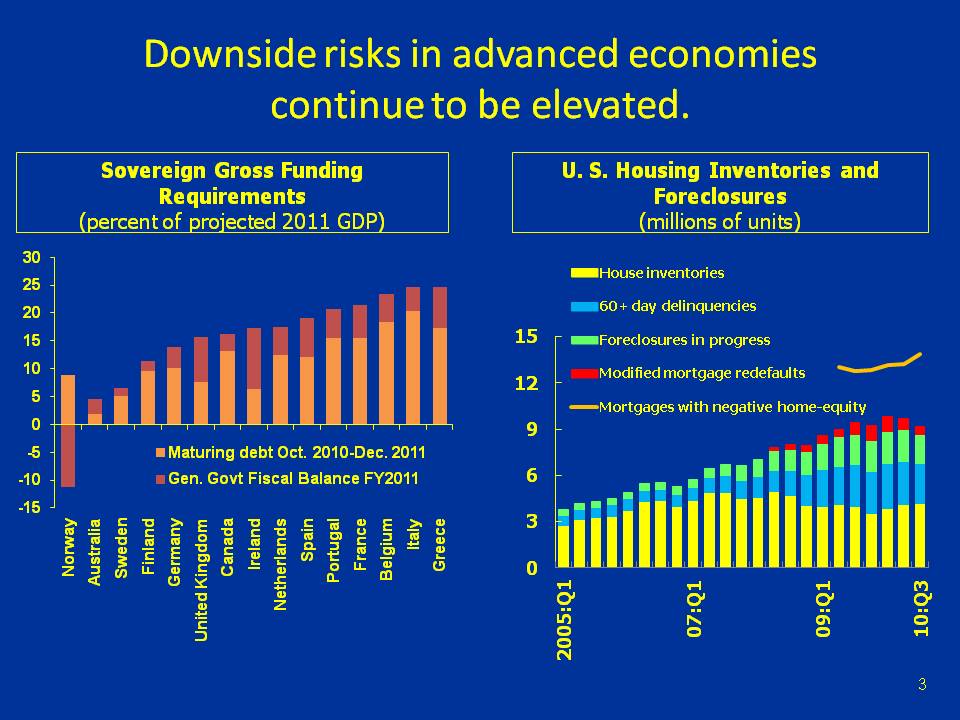

Chart 3

Financial market turbulence has receded in recent weeks, but underlying stresses in peripheral euro-area economies remain unresolved. Markets are anticipating that European policymakers will significantly strengthen their response to the ongoing crisis. Nevertheless, a key risk is turbulence in advanced sovereign debt markets that could be triggered by unsuccessful debt rollovers or underperformance relative to fiscal consolidation plans (left, Chart 3). Such an event could create renewed financial market dislocations that interrupt the transition toward stronger private-led demand. Another risk to the outlook stems from the possibility of renewed weakness in key property markets, including the United States (right, Chart 3).

Our baseline projections assume that current policy actions manage to keep the financial turmoil and its real effects contained in the periphery of the euro area, resulting in only a modest drag on the global recovery. This view reflects the limited financial spillovers observed so far across financial markets and regions, as well as the fact that policy responses following the Greek crisis helped limit its impact on the global recovery in the second half of 2010. For example, reaction in global debt and equity markets to the Irish crisis was more contained.

The risks for emerging economies are very different. They too face downside risks to growth, as, for instance, financial turbulence in advanced economies could spill over to the real economy and thus depress trade. But the principal concerns here are related to overheating and a rapid rise of inflation pressures—and these of course are key issues for central banks.

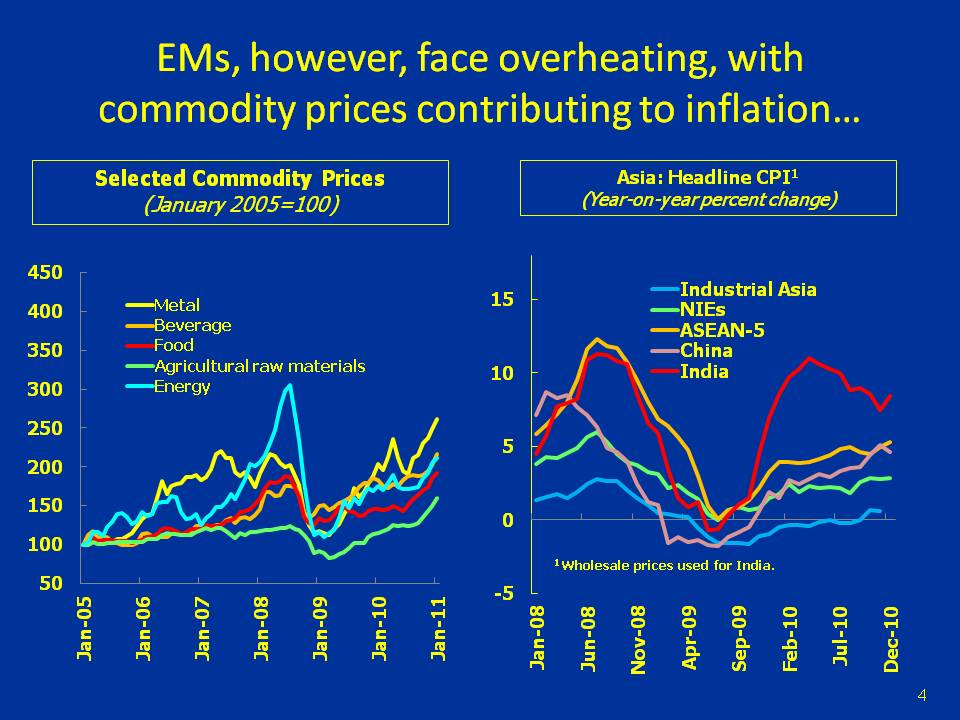

Chart 4

Prices for both oil and non-oil commodities rose considerably in 2010, partly in response to strong global demand, but also because of supply shocks for selected commodities, such as weather-related crop damage (left, Chart 4). Upward pressure on prices is expected to persist in 2011. The uptick in consumer price inflation in emerging economies in 2010 was attributable partly to rising food prices. But the recent bout of high food price inflation has been quite persistent and is beginning to feed into overall price inflation in a number of emerging economies (right, Chart 4). Certainly this is true in Sri Lanka, where recent flooding has—if only on a temporary basis—further exacerbated these international pressures.

More generally across the region, core inflation has also begun to rise—although the degree of acceleration has varied quite a bit across the region—suggesting that price pressures are broadening. Moreover, real wage growth has also picked up in a number of Asian economies on the back of relatively low and falling unemployment and anecdotal evidence of skill shortages.

Pressures are not limited to consumer prices and wages, however.

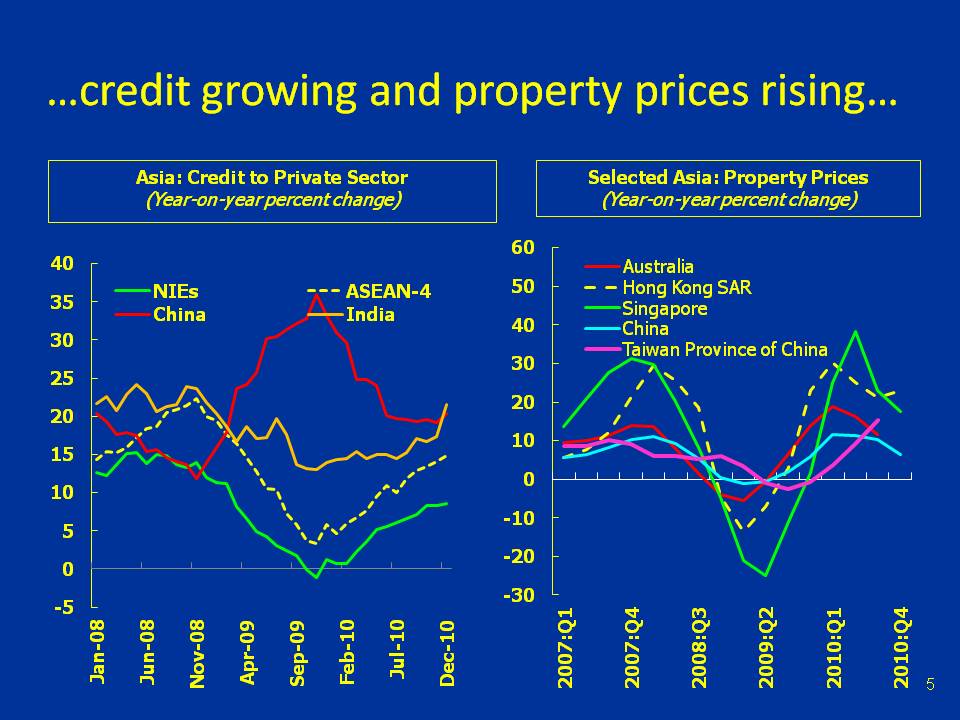

Chart 5

Credit growth, which slowed significantly during the global financial crisis, has turned the corner and is running at robust rates across emerging Asia (left, Chart 5). In fact, as financial conditions normalized, a number of regional central banks began monetary tightening in mid-2010. In Sri Lanka, after contracting for many months, credit has turned around and by December was up 25 percent year-on-year, albeit from a low base.

While upward price pressures in stock markets have lessened somewhat in recent months—in part reflecting markets’ anticipation of further tightening and a moderation of capital flows to emerging markets—such pressures have emerged in property markets in a few economies in East Asia (right, Chart 5). The risks that a property bubble could be inflating cannot be entirely ruled out if looking at specific segments of national markets, such as the high price markets in Singapore and Hong Kong, or a few cities in China. But at a national level, property prices have moderated their growth and do not seem to be significantly above fundamentals in these economies, partly reflecting measures that have been introduced, ranging from decreases in loan-to-value ratios to direct taxation of transactions. Sri Lanka’s property market remains subdued.

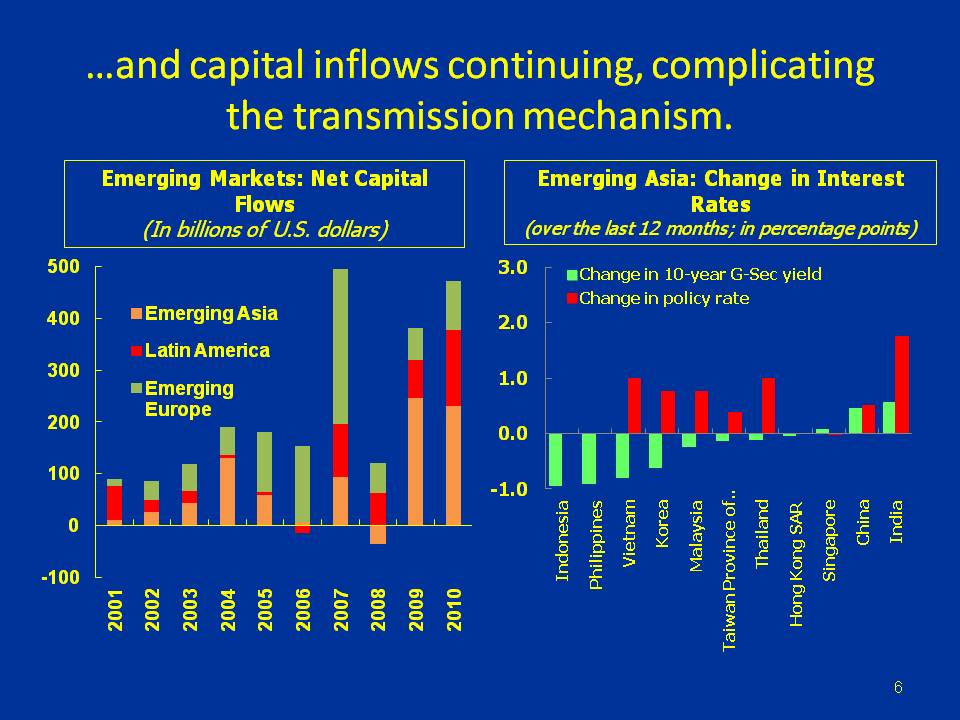

Chart 6

Given favorable growth and sovereign debt dynamics in comparison with advanced economies, not to mention interest rate differentials, Asia has attracted significant amounts of foreign capital—and in particular, volatile portfolio flows—since the global financial crisis, and these trends are expected to continue in 2011 (left, Chart 6).

Continued, large portfolio inflows could easily overwhelm emerging Asia’s modestly sized capital markets. Although, as I have explained, clear signs of bubbles are not evident at this stage, the risk of sharp asset price movements and destabilizing sudden stops or reversals of flows, particularly when risk sentiment shifts, cannot be ruled out. Moreover, managing the exit from policy stimulus might be complicated by the persistence of sustained capital flows to Asia, as rate hikes would only serve to boost such flows. Not only that, but in the presence of capital inflows and the corresponding high domestic currency liquidity, policy rate hikes may not directly translate into increases in interest rates in the economy (right, Chart 6).

Sri Lanka is one country that has faced a surge in capital flows. Starting in the middle of 2009, with the end of the civil conflict, the approval of the IMF program, and the return of global investor appetite, capital flows—along with a recession-induced compression of imports—permitted the central bank to rebuild its reserves from around one month’s import coverage to more than four months’ worth of goods and services imports, while keeping the exchange rate stable. On the other hand, intervention has led to excess rupee liquidity and attendant risks of a credit boom and high inflation, and the central bank, like many of its counterparts in the region, is grappling with how to manage these issues.

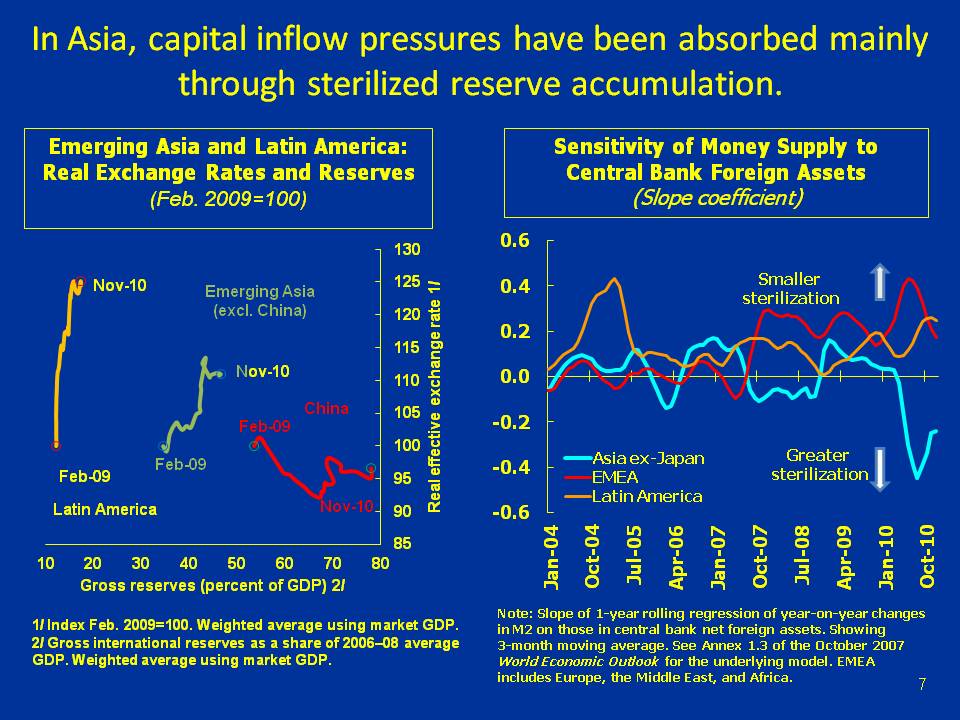

Chart 7

So far, most countries have relied on a combination of currency appreciation and reserve accumulation to accommodate capital inflows. Evidence suggests that reserve accumulation has absorbed a large fraction of the pressures from a return of capital flows, especially in the case of Asia (left, Chart 7), but this masks significant variation of the response between countries. On the one hand, India has abstained from intervention since end-2009, allowing the exchange rate to take the brunt of the adjustment; on the other hand, intervention was rapid in other countries, not to mention Sri Lanka, which I already discussed. However, compared with other regions, Asian policymakers have been particularly effective at controlling money growth in response to reserve accumulation, as evidenced by the relatively low sensitivity of money supply growth to the build-up in central bank foreign assets (right, Chart 7).

Going forward, greater exchange rate flexibility can offer an important buffer against the risk, which I described earlier, that large capital inflows may undermine efforts to tighten the monetary stance. With global interest rates likely to remain low, countries with tightly managed exchange rates in effect import easy global monetary conditions, unless they tighten capital controls.

Tighter fiscal policy could also achieve the same, but may not always be feasible. While sterilization policies in the region appear to have worked so far, as I mentioned, the question going forward is whether the structure of central banks’ balance sheets and the limited size and depth of domestic fixed income markets can support a significant further expansion in sterilization operations. This may require introducing new instruments, such as allowing central banks to issue their own paper where this is currently not possible.

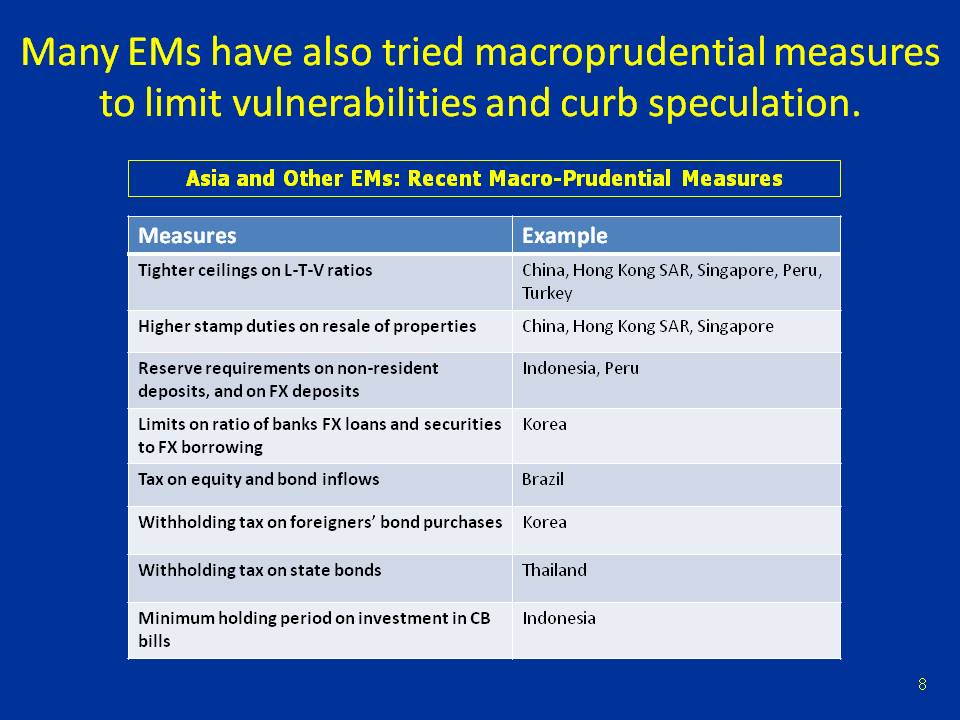

Chart 8

Extending the toolkit to macroprudential measures can also help mitigate the consequences of sizable and potentially volatile capital flows, and the Fund is looking at ways to make its advice more effective in this area. Several Asian economies have already implemented measures to safeguard financial and macroeconomic stability (table in Chart 8). These measures have mainly related to banking sector leverage, short-term foreign capital inflows, property price inflation, and foreign currency exposures. Sometimes, measures have been more successful in altering the nature of inflows rather than their size.

From a longer-term perspective, the key policy question of how to improve local market absorption to deal with persistent capital inflows still remains to be addressed. In this context, we should consider that large capital inflows into Asia are not only a challenge, but also present opportunities to facilitate medium-term rebalancing. The question is how capital inflows can be appropriately channeled toward financing broader-based growth. Two key things are needed: first, making long-term investment into Asia more attractive, for example, by lowering restrictions on foreign investment in the services sector as recently done in Malaysia, or by promoting private-public partnerships for much needed infrastructure investment; and second, promoting financial market development and access to finance, including for smaller and more service-oriented firms which remain credit-constrained.

Let me shift gears a bit from the topics of overheating and capital flows to consider some of the other shifts going on in the world economy, and what implications they have for monetary and other macroeconomic policymakers.

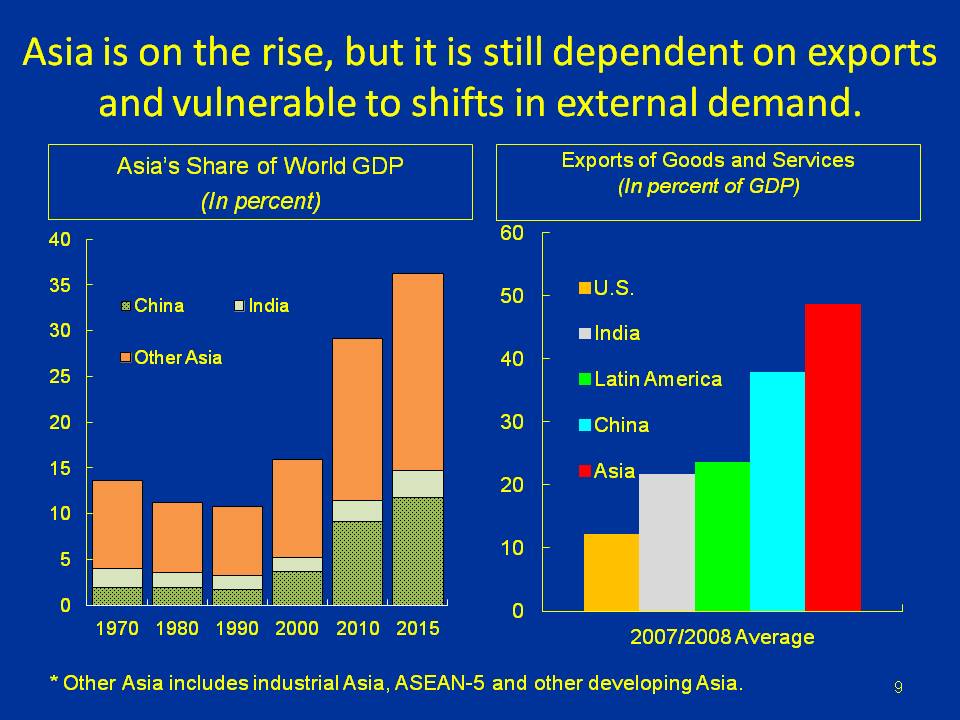

Chart 9

First, as I mentioned earlier, Asia is now driving the global recovery. And that is not just a temporary phenomenon. Asia’s share of world GDP has grown from 10 percent in 1990 to about 30 percent now and is expected to continue growing (left, Chart 9). Indeed, on current trends, by 2030, Asia’s GDP would be larger than that of the G-7 and half the size of the G-20’s.

A key fact to note, however, is that Asia is heavily trade dependent. A full 50 percent of GDP is accounted for by exports, while the comparable figure for the US is just 10 percent (right, Chart 9). And in the NIEs, trade openness ((exports + imports) / GDP) exceeds 100 percent! With this trade dependence, the result is vulnerability to shifts in external demand, implying that Asian economies are exposed to the downside risk of an advanced economy slowdown, as I described before.

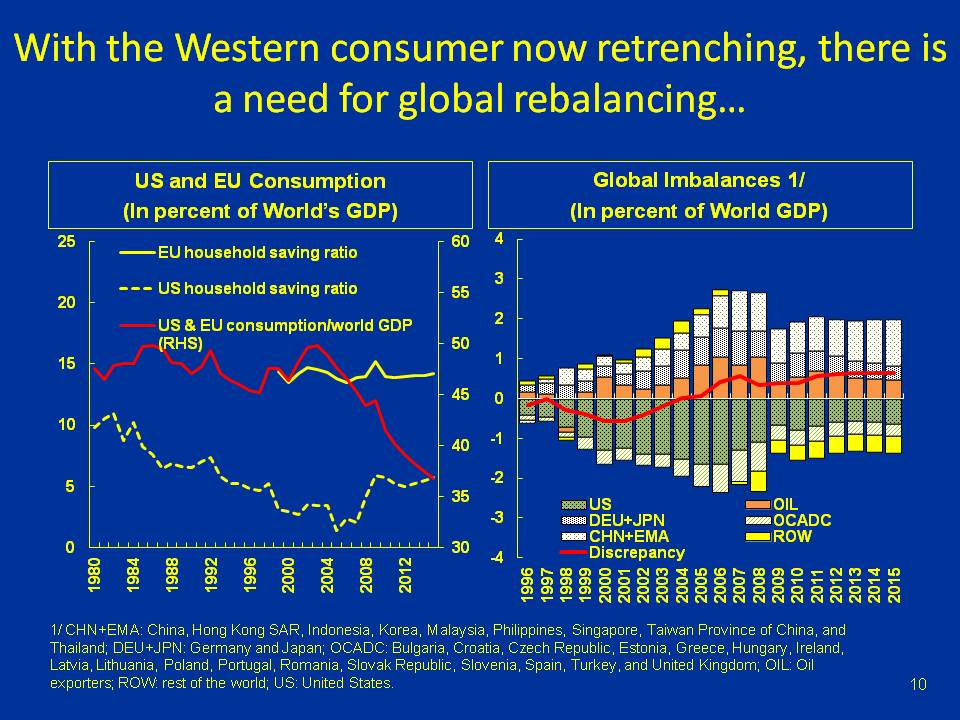

Chart 10

But more fundamentally, it implies that Asia’s fortunes are tied to developments in current-account-deficit economies. The free-spending Western consumer, who provided demand for exporters worldwide, has been chastened by the global crisis. With employment prospects insecure and having suffered substantial losses of wealth (especially in housing), she is now in a mode of retrenching—building wealth and raising saving. Indeed, we see that US and EU consumption has declined steadily as a percent of world GDP for many years—from a peak of nearly 50 percent—and is expected to continue doing so, falling to 35 percent in 2015 (left, Chart 10). Moreover, the US household saving rate, which approached zero during the boom years, has increased substantially and could remain high for a while.

The counterpart to this, of course, is that current account deficits in the West will become smaller, as will current account surpluses elsewhere (right, Chart 10). Just as some countries will need to increase saving, others will need to reduce it—namely current account surplus countries, including many in Asia. Domestic demand in Asia will need to step up as a new engine of global growth.

Certain policies can help boost Asian domestic demand—for instance, more spending on social safety nets, in order to reduce precautionary saving and boost consumption; or more infrastructure investment by government directly; or measures to develop financial markets, which can help boost both consumption and investment. And of course, there is also a role for exchange rate flexibility, which is why the issue of rebalancing is a critical one for central banks to consider.

Hence it is somewhat worrisome that only limited progress has been made toward reducing external imbalances after the global financial crisis. The current account balance in China is expected to have bottomed out in 2010 and projected to increase again over this year and the next (right, Chart 10). Current account surpluses are expected to decrease in NIEs and ASEAN economies, but only marginally. With the US current account deficit projected to stabilize at close to current levels over the next few years, it is no surprise that global imbalances are expected to remain and even worsen somewhat.

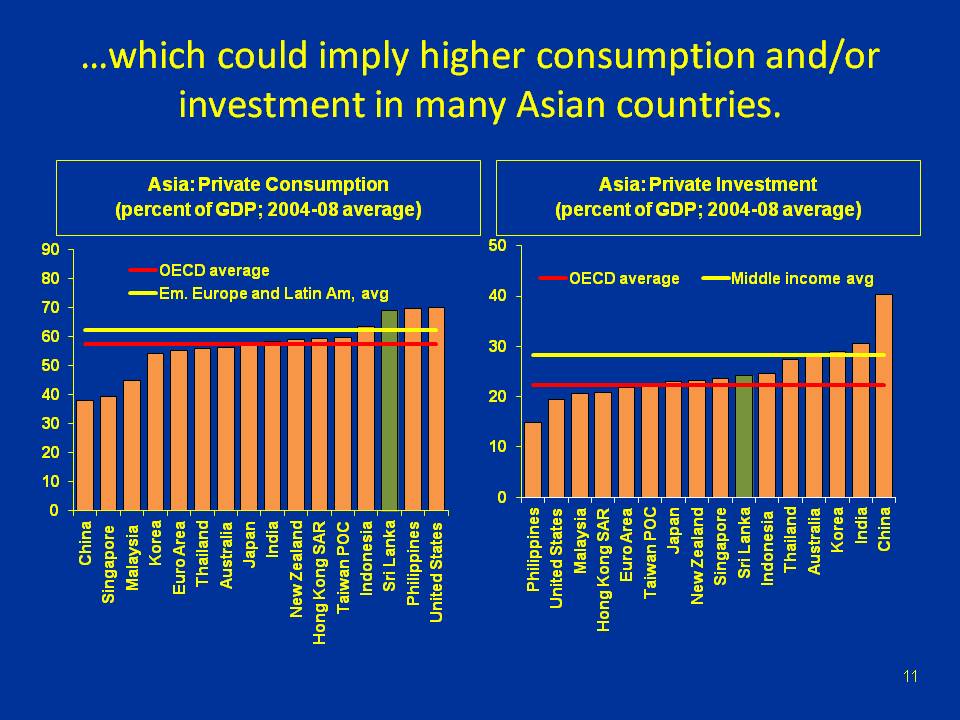

Chart 11

It is worth emphasizing that rebalancing will mean different things for different countries. Domestic demand in Asia as a whole will surely need to rise, driven by China, but this won’t necessarily happen in each country in the region. For instance, consumption is not generally weak in Asia, contrary to perceptions of an Asian savings glut. Rebalancing would clearly imply an increase in consumption for some countries, but many Asian economies, including Sri Lanka, already consume “enough” relative to OECD or emerging market benchmarks (left, Chart 11). Asia’s high current account surplus may also be the result of an investment slump. However, investment-to-GDP ratios across the region are not generally low, suggesting again some caution against generalization (right, Chart 11).

In Sri Lanka, for instance, instead of boosting domestic demand, a key priority will be restoring the country’s share of world exports, which has declined steadily over the past decade. Two important avenues to achieve this are increased regional integration—that is, reorienting exports from the US and Europe toward the fast-growing Asian economies—and enhancing export diversification and sophistication, to take advantage of new opportunities. The current strong recovery of the Sri Lankan economy makes the country well-placed to meet these challenges.

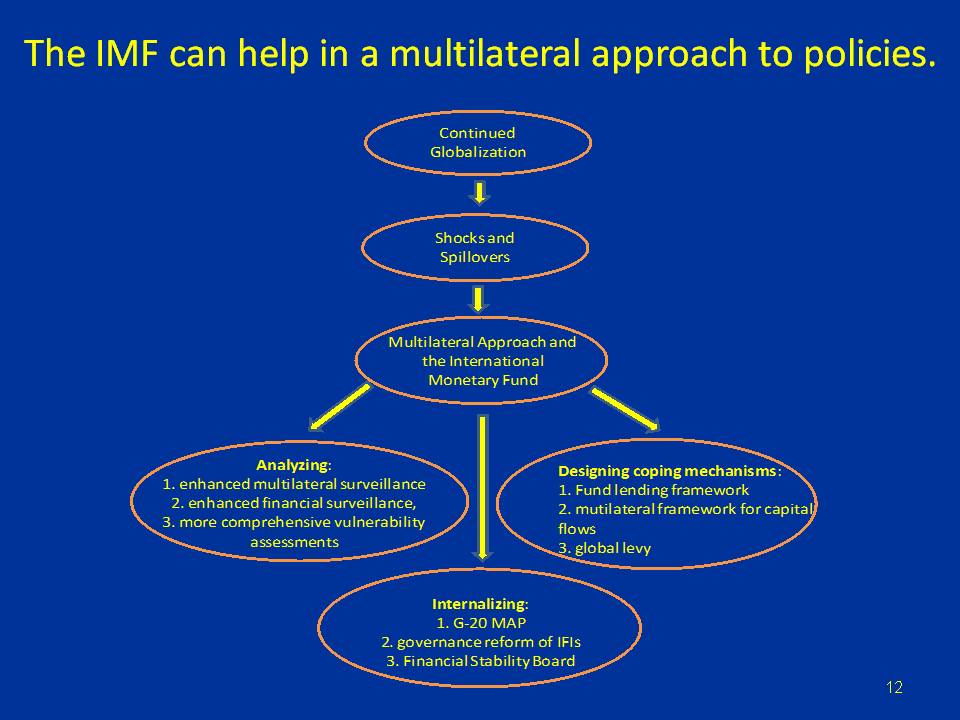

Chart 12

The main challenge for the global community is to pursue cooperative and well-timed policy initiatives. Such a multilateral approach can reduce vulnerabilities and rebalance growth. Both are needed to sustain the global recovery. Further, the international monetary system has in the past facilitated a period of unprecedented global economic growth and integration. However, it has also allowed the buildup of critical weaknesses at the core of economies issuing global reserve assets, prolonged external imbalances, and destabilizing capital flows, with only limited buffers against sudden liquidity shortages and exchange rate volatility. The IMF can facilitate a multilateral approach to policymaking and in reforming the international monetary system. (Chart 12) The focus of efforts must be twofold: (1) reducing the sources of volatility; and (2) developing tools to deal with volatility and shocks.

The launch of the G-20 Mutual Assessment Process (MAP) is a step in the right direction. A key goal must be to strengthen collaboration to capture policy interactions and spillovers. The IMF is contributing to this kind of analysis. The past decade has seen unprecedented growth in cross-border capital flows. As part of its work program, the IMF is developing a shared vision, and ideally, guiding principles on capital flows. This vision, as it were, would take into account the macroeconomic reasons for cross-border capital flows, the appropriate macroeconomic response by recipient countries, and the role of macro-prudential tools and other measures, including capital controls. A flip side of large cross-border flows is that every economy is more dependent on the availability of liquidity in times of stress. The IMF has enhanced its financial safety nets and is looking for ways to make them more effective. We will also strengthen our efforts to develop greater synergies with regional financing arrangements. Finally, a key part of the work program for the IMF is the issue of global reserve assets. The evolution of the system will necessarily be gradual and the choice of reserve assets will inevitably be a market decision. The potential role of the SDR in this context is worth studying with an open mind.

Summing up, let me say that the global recovery is set to continue, led by the Asian economies. But as the multispeed recovery proceeds, the policy challenges that have emerged since the crisis are becoming more pressing. Emerging market central banks will have to be vigilant against overheating. Capital flows will have the potential to worsen such overheating while also complicating the exercise of monetary policy, but they can also help in placing the global economy on a path to sustainable and balanced growth. For all of these issues, a multilateral approach is needed, and the IMF can play a role.

SEACEN governors and staff are grappling with these difficult issues on a daily basis, and it is my sincere hope that this conference will give you all the opportunity to share experiences and learn from one another, so that your central banks can operate ever more effectively in the challenging new environment that confronts us all.

Thank you.

IMF EXTERNAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT

| Public Affairs | Media Relations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-mail: | publicaffairs@imf.org | E-mail: | media@imf.org | |

| Fax: | 202-623-6220 | Phone: | 202-623-7100 | |