Construction of third bridge crossing lagoon in Ivory Coast's economic capital Abidjan. Investment in infrastructure has helped the country maintain robust growth (photo: Thierry Gouegnon/Reuters/Newscom).

Sub-Saharan Africa: Policy Adjustment Way Out of Growth Slump

October 25, 2016

- Growth at lowest level in more than 20 years

- Many non-commodity exporters still performing well

- Policy adjustment essential to boost growth in most-affected countries

Growth in sub-Saharan Africa is set to slow to its lowest level in more than two decades, the IMF said in its latest Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa.

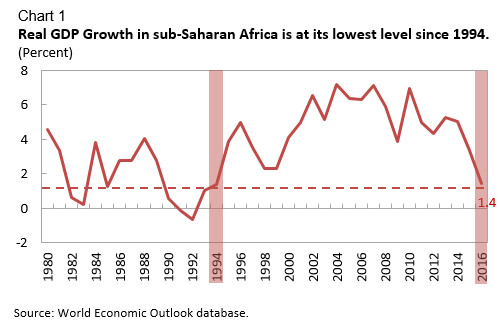

The report projects average growth to fall to 1.4 percent in 2016 (see chart 1), less than half of last year’s growth and far below the 5 percent plus experienced during 2010-14. GDP per capita will also contract for the first time in 22 years, according to the report.

The head of the IMF’s African department, Abebe Aemro Selassie, said there are two main factors behind this sharp slowdown: “First, the external environment facing many of the region’s countries has deteriorated, notably with commodity prices at multi-year lows and financing conditions markedly tighter. Second, the policy response in many of the countries most affected by these shocks has been slow and piecemeal, raising uncertainty, deterring private investment and stifling new sources of growth,” Selassie said.

Multispeed growth

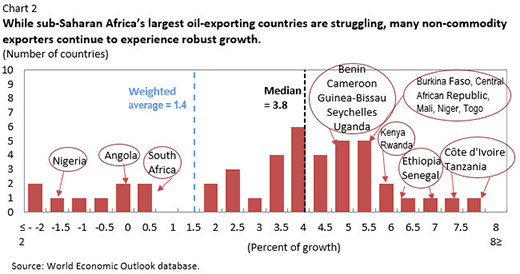

Yet, the report shows the full picture of sub-Saharan Africa is one of multispeed growth in which regional aggregate numbers hide considerable diversity in economic paths across countries (see chart 2).

Non-commodity exporters, around half of the countries in the region, continue to perform well with growth levels at 4 percent or more. Those countries benefit from lower oil import prices, improvements in their business environments, and strong infrastructure investment. Countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Senegal, and Tanzania are expected to continue to grow at more than 6 percent for the next couple of years.

Most commodity exporters, however, are under severe economic strain. This is particularly the case for oil exporters like Angola, Nigeria, and five of the six countries from the Central African Economic and Monetary Union, whose near-term prospects have worsened significantly in recent months despite the modest uptick in oil prices. In these countries, repercussions from the initial shock are now spreading beyond the oil-related sectors to the entire economy, and the slowdown risks becoming deeply entrenched.

Conditions in non-oil commodity exporters also remain difficult, including in South Africa where output expansion is expected to stall this year. Likewise, growth in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe is decelerating sharply or stuck in low gear. The challenges for several of these countries have been compounded by an acute drought affecting large parts of eastern and southern Africa.

Implementing prompt, comprehensive adjustment

The report shows that growth could recover to close to 3 percent in 2017 if policy makers, especially in the region’s largest economies, take strong action in the coming months.

While many of the hardest-hit oil-exporters have taken steps to adjust to the new reality of low commodity prices, Selassie said by and large, the adjustment has been too slow and incomplete. “Given the scale and persistent nature of the shock and limited policy buffers, a growth rebound will require a much more sustained adjustment effort, based on a comprehensive and internally consistent set of policies to reestablish macroeconomic stability,” he said.

For countries outside monetary unions, the report urges central banks to allow the exchange rate to fully absorb external pressures, and tighten monetary policy where needed to tackle sharp increases in inflation. The report also stresses the need to durably reduce fiscal deficits. For countries within monetary unions, where the exchange rate tool is not available, the burden on fiscal adjustment to deal with the shock is likely to be considerably greater still, and the report stresses that central bank financing of excessive fiscal deficits needs to be sharply curtailed.

Countries in the region that have continued to enjoy strong growth have also seen fiscal deficits widen and debt levels increase in recent years, largely due to stepped-up development spending. In those countries, the report shows there is a need to strike a better balance between increased investment spending needs and debt sustainability.

In two background studies, the Regional Economic Outlook also examines the evolution of exchange rate regimes in sub-Saharan African countries during the past 35 years, as well as the region’s high vulnerability to natural disasters and policy measures to mitigate their impact.