Policy Responses to Capital Flows

October 11, 2018

As prepared for delivery

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. It’s a great pleasure to join you today, during the Fund’s 2018 Annual Meetings, to discuss a topic that’s vitally important to international financial stability and the global economy.

Capital flows can deliver substantial benefits for countries. They tend to be greater for countries whose financial and institutional development enables them to intermediate capital flows safely.

However, capital flows also have the potential—if they are not carefully monitored—to contribute to excessive credit expansions and a buildup of systemic financial risk. The risks from capital flows, including heightened macroeconomic volatility and vulnerability to crises, are well known from the experiences of emerging markets (EMs) and other open economies. These risks came into sharp focus again around the time of the global financial crisis (GFC) from 2007 to 2009: Vulnerabilities in financial systems built up in tandem with increasing cross-border interconnectedness and spillovers from source countries’ policies. That sowed the seeds for large adverse effects once markets seized up, capital flows reversed, and balance sheets unwound.

Managing the risks that stem from capital inflows, while maximizing their benefits, requires a careful calibration of policy responses, especially in an environment of large and volatile capital flows. In addition to the appropriate macroeconomic adjustments, further policy responses could prove useful, to prevent excessive credit booms that often lead to busts.

In my remarks here today, I will document the relationship between capital inflows and credit expansions, and I will outline the Fund’s approach to adding macroprudential policies, capital-flow management measures, and foreign exchange (FX) intervention to the mix of policy responses to potentially disruptive capital flows. I will also discuss how recent capital flow developments in emerging markets have prompted varying responses from affected countries. I will conclude by emphasizing the importance of the right policy mix being tailored to countries’ individual circumstances.

Capital Inflows and Credit Expansions

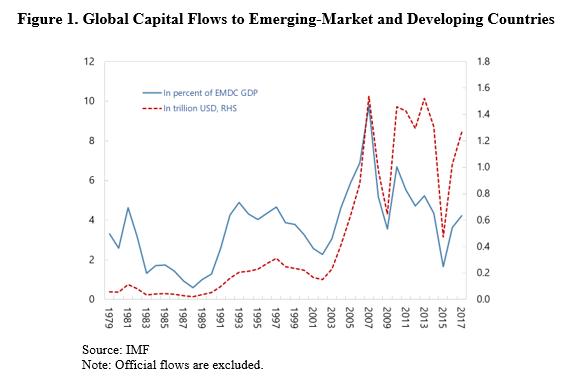

Financial globalization has led to a dramatic increase in global capital flows to emerging-market and developing countries (EMDCs) over the past several decades, particularly from the early 2000s. However, there have been periods of sharp reversals. As Figure 1 shows, the reversals in 2008 in the wake global financial crisis, and in 2013 during the “taper tantrum,” were particularly notable episodes.

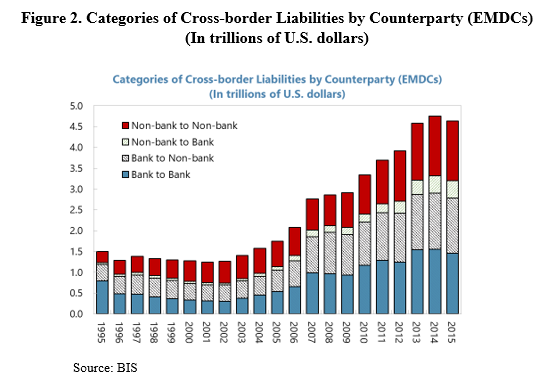

Looking at capital flows from the stock perspective, EMDCs’ cross-border liabilities more than tripled since 2000 (Figure 2). The rise in flows from banks to non-banks, and from non-banks to non-banks, was a particularly strong driver of the buildup in cross-border liabilities. While aggregate capital flows have declined following the GFC, owing particularly to the decline in bank flows among advanced economies, capital flows to EMDCs have been more persistent. They have been fueled by bank flows in Asia and, to a lesser extent, by bond portfolio flows in Latin America.

Greater efficiency, strengthened financial sector competitiveness, the financing of productive investment, and enhanced investment and consumption smoothing are key benefits of capital flows. This can lead to greater financial depth and greater financial inclusion, as well as to stronger GDP growth. At the same time, capital flows have contributed to excessive credit expansions and systemic risk in several cases. Moreover, when capital flows reverse, it can lead to heightened macroeconomic volatility and can adversely affect financial stability. The key challenge is macro risk management.

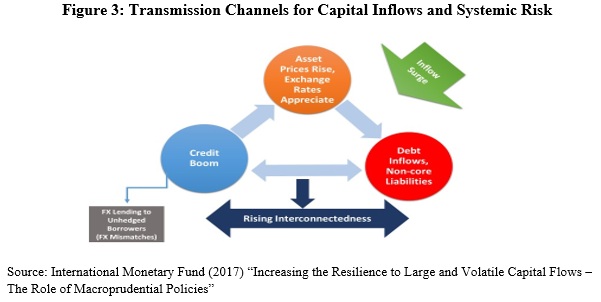

As set out in the IMF’s 2017 Policy Paper on capital flows and macroprudential policy, capital flows are linked to increases in systemic risk through a range of channels (Figure 3):

- An inflow surge will increase the local exchange rate and other asset prices. This can induce an expansion of credit through several mechanisms:

⚬ First, when the domestic currency appreciates and when asset prices rise, this increases the value of local collateral, and therefore the capacity of local agents to borrow against collateral;

⚬ Second, it simply makes local borrowers feel “richer,” boosting their demand for credit; and,

⚬ Third, it reduces default risk as perceived by lenders, and it relaxes funding constraints, making banks more confident to extend credit.

- There is also a link between domestic credit and an expansion in cross-border credit. This “non-core funding channel” works in two ways:

⚬ First, when capital flows in, it eases borrowing constraints for local banks, which can more easily tap wholesale funding and use this to increase domestic credit. Capital inflows and easy global financial conditions then “push up” domestic credit.

⚬ Second, when domestic credit grows strongly, this can outpace domestic deposit growth. Local banks then turn to wholesale funding sourced in international markets to satisfy local credit demand. That is, strong domestic credit “pulls in” further investment flows, potentially leading to more vulnerable funding structures.

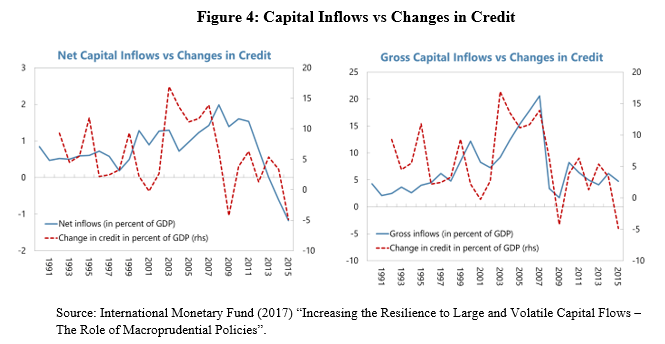

There is a positive correlation between capital flows and credit for both emerging and advanced open economies, as Figure 4 shows. The correlation is tighter for gross flows than for net flows, an issue that deserves to be explored further. The correlation has been strong particularly in the run-up to, and in the period around, the GFC.

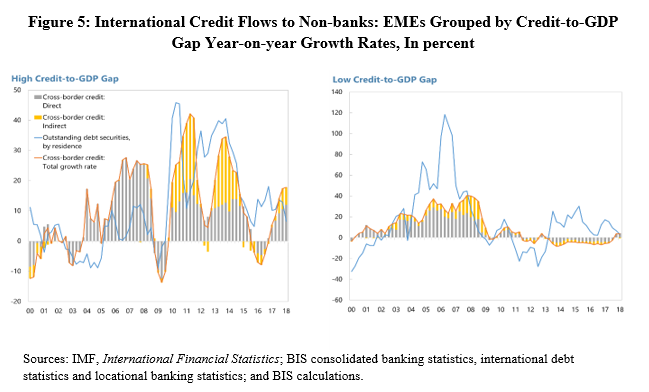

Figure 5 plots the direct (cross-border borrowing by non-banks) and indirect (cross-border borrowing by banks) components of cross-border credit growth for selected EMs. The countries were grouped into a high and a low credit-to GDP group. As the chart shows, credit moves more tightly with capital inflows in countries with high credit-to-GDP gaps:

- The high credit-to-GDP gap group (left panel) has had a particularly high cross-border credit growth rate for most of the period since the GFC.

- In the low credit-to-GDP gap group, on the contrary, cross-border credit growth has been moderate in the past 10 years (right panel).

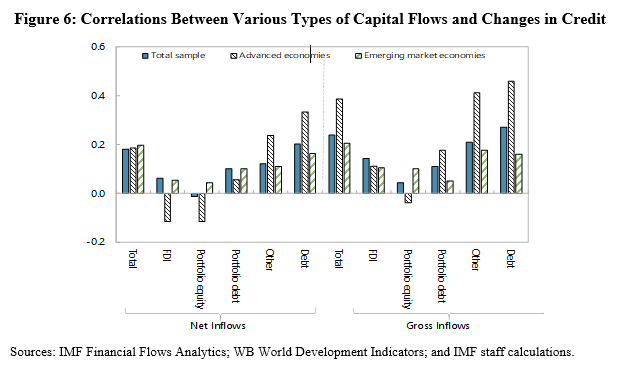

Moreover, as shown in Figure 6, the composition of capital inflows matters:

- The strongest relationships have been established between non-Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) flows, particularly gross debt flows, and credit booms.

- An increase in domestic credit is associated with a significant increase in “other investment flows” – mainly cross-border bank credit.

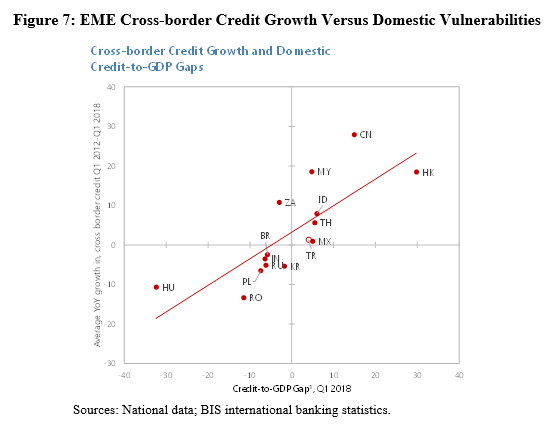

The positive relationship between growth in cross-border credit and the credit-to-GDP ratio over the last five years in EMs indicates that cross-border credit growth is associated with increasing domestic vulnerabilities. Figure 7 shows the recent relationship between cross-border credit growth and indicators of the domestic credit cycle at the country level. The most vulnerable countries are located in the upper-right quadrant, where a high credit-to-GDP gap is coupled with high external borrowing in recent years.

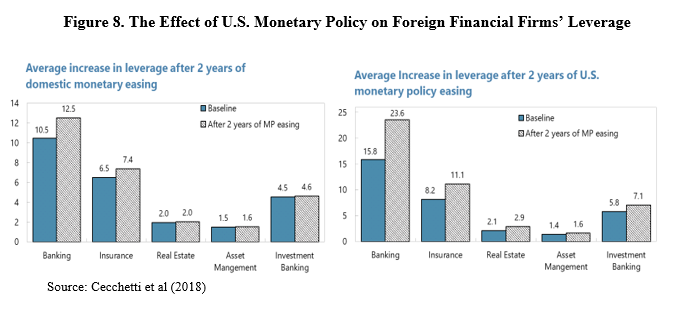

Cecchetti et al (2018) find that prolonged easing of monetary policy in the United States tends to fuel rising financial sector leverage in other countries (Figure 8). Such international spillovers are found to play a more important role in the leverage buildup than easing of domestic monetary policy. Countries’ resilience to tighter global financial conditions (as a result of the U.S. monetary policy normalization) will then depend on how successfully they manage to limit the buildup of macro-financial imbalances while strengthening buffers during the low-for-long era.

Policy Frameworks

I will now turn to policies and policy frameworks in emerging economies that have a bearing on the management of capital flows.

Certain countries have shock absorbers to deal with large and potentially volatile capital flows. Such “baseline” countries are characterized by (i) a fully flexible exchange rate; (ii) an open capital account; (iii) a credible and effective monetary policy framework such as inflation targeting; and (iv) a resilient financial sector. In these countries, macro, exchange rate, and asset price adjustments absorb shocks.

However, even in these cases, certain key preconditions are needed for the shock absorbers to work effectively. Those preconditions are:

- Well-developed and transparent financial markets, including deep hedging markets

- Strong micro- and macroprudential supervisory and legal frameworks

- Adequate information for the calibration of effective macroprudential instruments

- Data and policy transparency

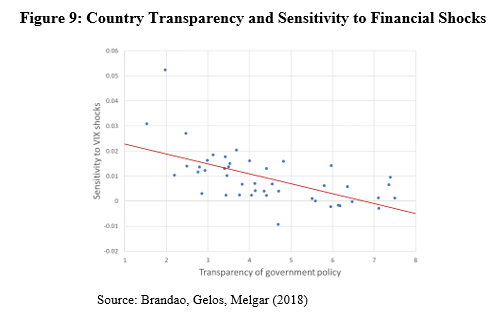

Let me elaborate on that last point. A recent paper by my colleagues at the IMF [i] finds that more transparent government policies and better corporate disclosure significantly reduce the sensitivity of EM assets to global shocks. Using daily data for 62 stock and bond markets over the period from 1992 to 2017, they find that developed and emerging markets that score worse on various dimensions of opacity react more strongly to global market conditions [ii] than those that are more transparent (as seen in Figure 9). The policy implication is that, by increasing transparency, countries can protect themselves against some of the unpleasant side effects of financial integration, such as excessive volatility.

Many countries do not possess these baseline characteristics or preconditions. A further complication for policy response is that the channels of transmission, from capital flows to systemic risk, can be difficult to disentangle and adequately assess in real time, as the impact of external shocks on specific countries will be conditioned by their circumstances.

Therefore, in addition to macroeconomic adjustments and structural policies, countries have been using a mix of other policies to prevent the buildup of systemic risk. These policies include:

- Macroprudential Measures (MPM)

- Capital Flow Measures (CFM) and CFM/MPMs

- Foreign Exchange Intervention (FXI)

Let us take a closer look at each of these policies, in turn.

Macroprudential Measures

Macroprudential policy pursues three interlocking objectives:

1. Increasing the resilience of the financial system to aggregate shocks by building buffers that help maintain the ability of the financial system to provide credit to the economy under adverse conditions.

2. Containing the buildup of systemic vulnerabilities over time by reducing procyclical feedback between asset prices and credit, and by containing unsustainable increases in leverage and volatile funding; and

3. Controlling structural vulnerabilities within the financial system by managing risks from interlinkages that can render individual institutions “too important to fail.”

As we have emphasized in the IMF’s policy papers, macroprudential measures should be tailored to material sources of vulnerability and should consider the transmission mechanisms of various tools in addressing risks.

- Vulnerabilities from credit booms can be addressed by broad-based tools that affect a wide range of bank activities of the banking system, such as countercyclical capital buffers or leverage ratios.

- Where vulnerabilities arise from excessive credit to the household sector, and from procyclical feedback between credit and asset prices, our advice is to use household sectoral tools, such as sectoral capital requirements (risk weights), loan-to-value (LTV) ratios, and debt-service-to-income (DSTI) ratios.

- Where systemic risks arise from increases in exposures to the corporate sector, such as increases in corporate leverage, lending to commercial real estate (CRE) or from FX lending to the corporate sector, it is best is to use targeted corporate sectoral tools, such as sectoral capital requirements (risk weights) and exposure caps.

- Vulnerabilities to systemic liquidity and currency risks can be addressed by liquidity tools, such as liquid asset ratios, stable funding requirements, and limits on FX open positions.

- Structural risks of contagion transmitted through interlinkages within the financial system can be addressed by a range of tools, including capital and liquidity surcharges for systemically important institutions, and measures to control interlinkages in funding and derivatives markets.

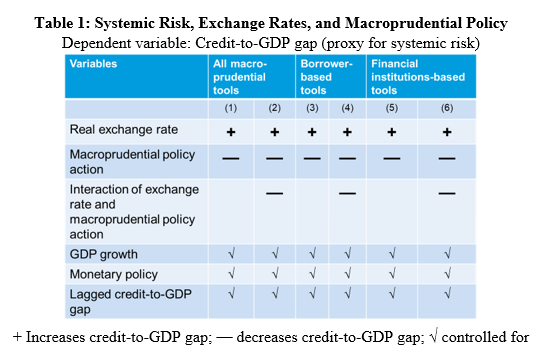

A forthcoming IMF paper [iii] examines the effectiveness of macroprudential policies in the context of capital flows for a panel of 62 advanced and emerging-market economies using quarterly data from 2000 to 2016. When the credit gap is regressed on past changes in real exchange rates, they find a robust relationship between exchange rate movements and credit developments. [iv] An appreciation of the local exchange rate against the dollar is associated with an expansion in the credit gap. Interestingly, this relationship is most pronounced for non-G7 economies that are financially open, as measured by the size of external financial assets and liabilities as a share of GDP.

But, significantly, macroprudential policies can attenuate this effect. Not only do macroprudential policies slow increases in the credit gap, they also flatten the relationship between exchange rate movements and increases in the credit gap. That is: For a given increase in the local exchange rate, the effect on domestic credit is less when macroprudential policy is tight. Further analysis suggests that this effect is strongest for borrower-based tools, such as LTV and DSTI, but it is also present for some financial-institution-based tools, in particular liquidity requirements.

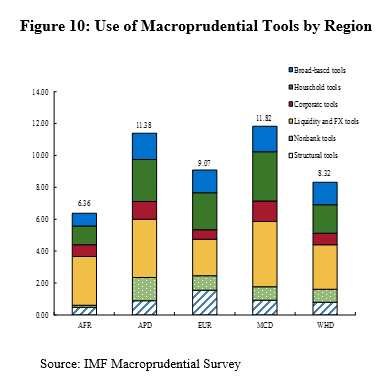

The IMF’s New Macroprudential Survey [v] reveals that countries around the world are making use of tools across all of these categories. As Figure 10 shows, liquidity and FX tools are most commonly used overall, including in Latin American countries. Household sector tools, such as LTV and DSTI, are the second-most-commonly used set of tools globally, even as they are less common in Western Hemisphere countries compared to most other regions.

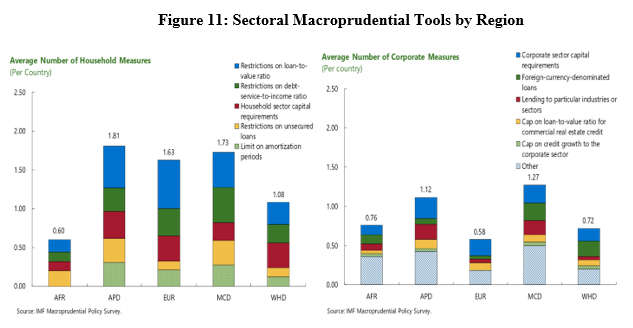

When we zoom in on household sector tools, we find that restrictions on loan-to-value and debt-service-to-income are most frequently used globally (Figure 11). These tools are especially common in Asia, Europe and the Middle East, with about half of countries in these regions maintaining this tool. However, as we observed before, these tools are less commonly used in Western Hemisphere countries, where only about a quarter of countries reported using these tools.

By contrast, tighter capital requirements on exposures to the household sector are common across all regions, including in the Western Hemisphere. For instance, Argentina applies a higher risk weight for loans at LTV ratios above 75 percent. Compared to household sector tools, measures to manage risks from exposures to the corporate sector are less common. The most frequently used ones are additional capital requirements for loans to the corporate sector, including for exposures in FX, as well as caps on FX lending, which are quite common even in Latin America.

There are some useful lessons from country experiences with macroprudential policy to date. One such lesson is that it is useful to adopt a portfolio approach: For instance, to address risks in housing markets, it is useful to combine limits on LTV, limits on DSTI and amortization requirements. In the absence of a DSTI limit, LTV limits can be circumvented by borrowers obtaining an (unsecured) loan to cover the down payment (as has been the experience in Sweden and China). A DSTI limit can counter this, and can also protect against additional sources of risk, such as shocks to income and interest rates. However, a DSTI limit may lead borrowers to prefer ever-longer-maturity loans, or loans that do not amortize, in order to keep debt service within the limit. To counter this, a minimum amortization requirement can be introduced (as in Canada, Hong Kong SAR, Israel, Hungary, Portugal, and Singapore).

Second, it can be useful to introduce “speed limits” (as in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and most recently Portugal) where a certain fraction of banks’ exposures is allowed to be outside of the limit. This can reduce efficiency costs, when the bank assesses that the borrower is a good credit but would not otherwise be able to grant the loan.

Third, it can be useful to take steps well before vulnerabilities have built up (and before credit gaps widen measurably). This is because we want to lock in the resilience benefit of macroprudential policy action early (as has been the approach in Ireland and the United Kingdom, for instance). As I have emphasized before, “Taking out insurance when financial conditions are easy is cheap. [vi]”

Capital Flow Measures

Since its adoption in 2012, the IMF’s Institutional View (IV) on capital flows has provided a framework for consistent policy advice to member countries on liberalizing and managing capital flows. The IV recommends that:

- capital flows should be primarily handled through macroeconomic policies, which in turn need to be supported by sound financial supervision and regulation and strong institutions;

- in certain circumstances, CFMs — which are measures designed to limit capital flows — can be useful to support macroeconomic adjustment and to safeguard financial stability; and

- CFMs should not substitute for warranted macroeconomic adjustment.

In the context of capital-inflow surges, CFMs may play a useful role particularly when: (i) the room for adjusting macroeconomic policies is limited; (ii) appropriate policies require time to take effect; and/or (iii) the inflow surge contributes to systemic financial risks.

Measures that are designed to limit capital flows and to reduce systemic financial risks stemming from such flows are classified as both CFMs and MPMs (CFM/MPMs). For this type of measure, the Fund’s two frameworks for capital flow management and macroprudential policy apply.

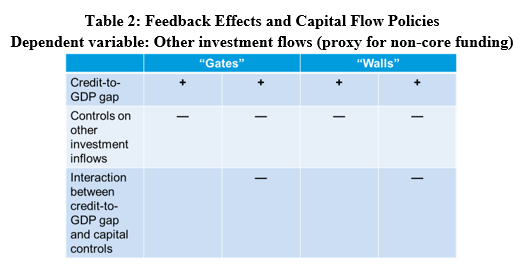

The research I cited previously, by Nier, Olafsson and Rollinson, also examines the effectiveness of capital flow management measures in the context of credit booms [vii] . They find that increases in the credit gap lead to an increase in non-core funding (measured by “other investment flows”). That is, an increase in credit leads banks to “pull in” additional cross-border funding (Table 2). They also find that restrictions on such “other investment flows” can break this link, helping avoid an increase in systemic risk from potentially volatile funding structures. This effect is present to some extent both for a temporary tightening of capital account restrictions — that is, the closing of “gates” — but also, and indeed more strongly for the existing stock or “wall” of longstanding capital account restrictions.

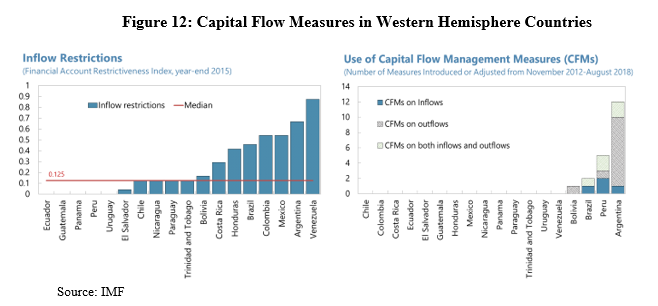

Let me focus on our findings for countries in the Western Hemisphere as they are of particular interest for us here today. We find that in general, Western Hemisphere countries vary in terms of their capital account openness as seen in the left panel in Figure 12. But most of them have in common that they have not introduced new CFMs or adjusted their existing measures recently. This is evident from the Fund’s new Taxonomy of CFMs, which contains information about measures that are assessed by Fund staff as CFMs and that are discussed in published IMF staff reports since the adoption of the Institutional View in November 2012. The right panel of Figure 12 shows that, apart from the crisis measures in Argentina, only eight CFMs were introduced or adjusted over this close to six-year period – mostly in response to inflows by utilizing specific reserve requirements or taxes.

Foreign Exchange Intervention

Intervention in foreign exchange markets is also a common response to capital inflows—including in emerging market countries with flexible exchange rate regimes. A key motivation for interventions cited by EM central banks is the concern about financial stability. Such a concern often reflects the presence of substantial unhedged currency mismatches on private sector balance sheets, which can cause large losses in case of sharp currency movements.

Worries about sharp currency movements at a later time may lead central banks to “lean against the wind” if they believe short-term pressures are moving the exchange rate away from its longer-term equilibrium level. The desire to build foreign currency reserves is also a common driver of FX intervention.

Financial stability aside, interventions can also be motivated by macroeconomic considerations. Central banks may worry that exchange rate volatility has an undesirable impact on inflation, or that overly rapid exchange rate adjustment negatively affects growth.

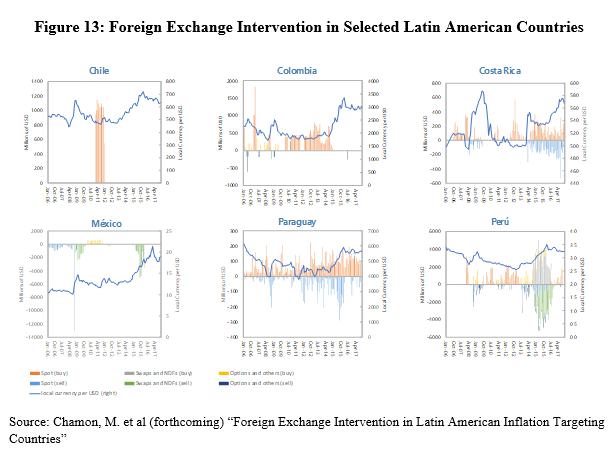

FX intervention is widely used in Latin America, although the frequency of interventions differs across countries. Many countries in the region have accumulated reserves as they leaned against sustained capital inflows. In some cases, those reserves were also deployed at times of depreciation pressures. Figure 13 is taken from a forthcoming book that documents the Latin American experience with FX intervention [viii] .

The book finds that:

- FX intervention plays a larger role in highly dollarized economies (such as Peru), in line with the financial stability motive in the context of large currency mismatches;

- Derivatives intervention (as opposed to spot-market intervention) has been employed to address hedging needs and to preserve FX reserves;

- Rules-based intervention helped transparency in some countries, avoiding the perception of a targeted level of the exchange rate (Colombia, Mexico); and

- More broadly, clear communication and transparency around interventions have been key to preserving the credibility of monetary policy.

Recent Capital Flow Developments in Emerging Markets

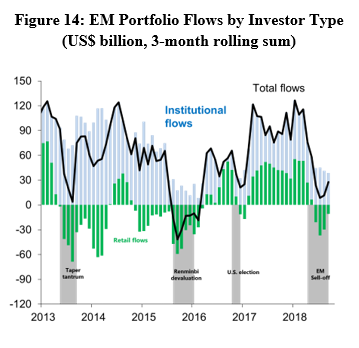

Portfolio flows to emerging markets have been under pressure recently. These flows have fallen sharply but have remained positive year-to-date, as shown in Figure 14. The decline has been driven mainly by retail flows, which turned negative during the selloff in the second and third quarter of 2018. Inflows from institutional investors are estimated to have declined as well but remained positive. Debt portfolio flows were particularly affected, after strong inflows in 2017.

U.S. monetary policy normalization had been expected to weigh on portfolio flows to emerging markets, but the actual reduction in inflows was larger than expected. This is in part because, over the past year, market participants have substantially revised upward their expectations for the likely path of US interest rates, pricing in several additional policy rate hikes.

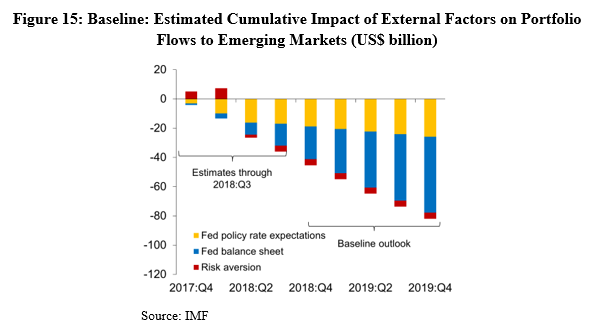

Looking ahead, emerging markets will probably continue to face reduced portfolio flows, given the ongoing U.S. monetary policy normalization. While the Federal Reserve’s policy rate hiking cycle is already well under way, the pace of balance sheet contraction is set to accelerate, reaching its maximum in the current quarter, the fourth quarter of 2018. Figure 15 shows the estimated cumulative impact of the U.S. monetary policy normalization on portfolio flows to EMs. The estimated cumulative decline in net non-resident portfolio equity and debt flows through the end of 2019 is about $80 billion, with much of the additional impact expected in 2019 due to the Fed’s balance sheet reduction. This further reduction in inflows will pose challenges to countries that rely heavily on external financing.

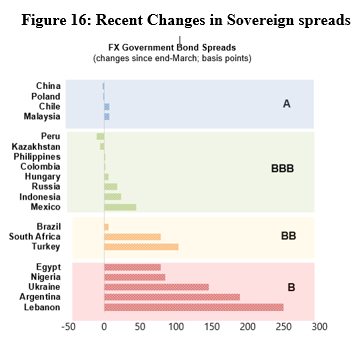

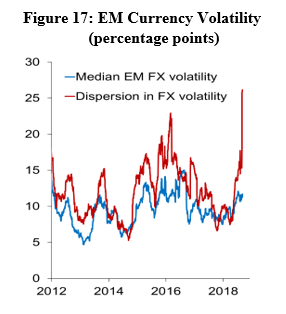

While global factors affected all countries, the overall spillovers across emerging markets have so far been relatively contained, and idiosyncratic factors have explained much of the outsized asset price moves. In credit markets, the widening of spreads on hard currency sovereign bonds has been more pronounced in lower-rated issuers (Figure 16), suggesting that investors have continued to differentiate between borrowers based on economic fundamentals and other country-specific factors. Investors’ differentiation is also reflected in greater dispersion in exchange-rate volatility, as shown by the red line in Figure 17. Another important point to emphasize is that there is limited evidence of contagion so far, given strong global risk appetite. However, if global risk appetite were to weaken, the risk of contagion could rise.

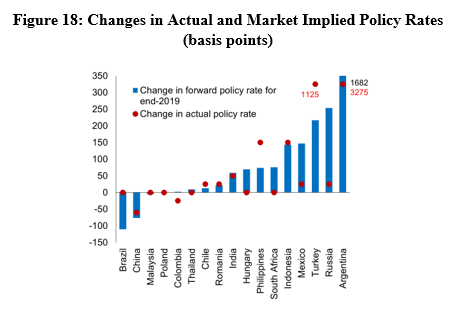

EMs’ policy responses to recent market pressures have varied. Facing external pressures, central banks in several emerging market economies responded with interest rate hikes (Figure 18) and interventions in currency markets (Figure 19). Argentina and Turkey reacted by raising policy rates sharply, while countries already in a tightening cycle (including Indonesia, Mexico, and the Philippines) hiked rates by more than markets had expected. Foreign exchange interventions were carried out in the spot market (Argentina, Indonesia) and via derivatives (Argentina, Brazil, India, Turkey).

Conclusion

Our main policy advice remains that exchange rate flexibility should be used as a key shock absorber. Appropriate macroeconomic policies should always be the core of the policy response — coupled, if necessary, with macroprudential policies to contain systemic risk and FX interventions. Policy rate hikes should counter inflationary pressure from currency depreciation and market pressures from outflows. FX interventions can be used to prevent disorderly market conditions, if reserves are adequate. Capital Flow Measures can be implemented in certain situations — but they should not be used as substitutes for needed macroeconomic adjustment. Instead, they should be temporary, transparent, and part of a broader policy response.

There is “no one size fits all” solution. Countries’ choices of their policy mix can be conditioned by several factors. The most important among such factors include: the type of capital inflows; the type of financial and macroeconomic vulnerabilities; the monetary policy framework and its credibility; and institutional capacity.

With that, I would be happy to answer your questions.

Literature

Adrian, Tobias, Richard K. Crump, Emanuel, Moench, (2013) “Pricing the term structure with linear regressions.” Journal of Financial Economics 110 (1), 110–138.

Bekaert, Geert and Marie, Hoerova, (2014). "The VIX, the variance premium and stock market volatility ," Journal of Econometrics, Elsevier, vol. 183(2), pages 181-192.

Brandao-Marques, Luis, Gaston Gelos, Natalia Melgar (2018) “Country transparency and the global transmission of financial shocks”, Journal of Banking and Finance. Volume 96, November 2018, Pages 56-72.

Cecchetti, Stephen, Mancini-Griffoli, Tommaso, Narita, Machiko, Sahay, Ratna (2018) “U.S. or Domestic Monetary Policy: Which Matters More for Financial Stability?” (current draft as of October 23, 2018).

Foreign Exchange Interventions in Inflation Targeters in Latin America, edited by Alejandro Werner, Marcos Chamon, David Hofman, and Nicolas E. Magud (forthcoming).

International Monetary Fund (2018) “The IMF’s Annual Macroprudential Policy Survey— Objectives, Design, and Country Responses,” IMF Policy Papers.

International Monetary Fund (2017) “Increasing the Resilience to Large and Volatile Capital Flows – The Role of Macroprudential Policies,” IMF Policy Papers.

International Monetary Fund (2014) “Staff Guidance Note on Macroprudential Policy,” IMF Policy Papers.

International Monetary Fund (2013) “Key Aspects of Macroprudential Policy,” IMF Policy Papers.

Nier, Erlend, Thordur Tjoervi Olafsson and Yuan Rollinson (2018) “Exchange Rates and Systemic Risk: The Role of Macroprudential Policies in Attenuating the Credit Cycle” forthcoming.

Endnotes

[i] Luis Brandao-Marques, Gaston Gelos, Natalia Melgar (2018) “Country transparency and the global transmission of financial shocks”, Journal of Banking and Finance

[ii] As measured by the U.S. equity returns, the VIX, Bekaert and Hoerova’s (2014), conditional variance index, and Adrian et al.’s (2013), U.S. term premium.

[iii] Nier, Olafsson and Rollinson (forthcoming) “Exchange Rates and Systemic Risk: The Role of Macroprudential Policies in Attenuating the Credit Cycle”

[iv] The panel regressions are based on a sample of 62 economies (35 advanced and 27 emerging), using quarterly data from 2000Q1 to 2016Q4. The credit-to-GDP gap is regressed on its own lag, the lagged value of an index of macroprudential action, the one-quarter-lagged year-on-year change in the real exchange rate, macroeconomic controls and country- and time-fixed effects. Estimation is based on a dynamic panel (Arellano-Bond) GMM estimator.

[v] The IMF’s macroprudential survey can be found at https://www.elibrary-areaer.imf.org/Macroprudential/Pages/Home.aspx

[vi] See Adrian, 2017.

[vii] The panel regressions are based on a sample of 62 economies (35 advanced and 27 emerging), using quarterly data from 2000Q1 to 2016Q4. The four-quarter average of gross other investment inflows is regressed on its lagged value, the lagged credit to GDP gap, a lagged index of inflow restrictions, and time-fixed effects. Estimation based on a random effects estimator.

[viii] Foreign Exchange Interventions in Inflation Targeters in Latin America, edited by Alejandro Werner, Marcos Chamon, David Hofman, and Nicolas E. Magud (forthcoming)

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org