The Paraguayan capital, Asunción: the country has the pandemic under control and COVID-19 deaths have been very low. (photo: Julio Ricco/iStock/Getty)

Paraguay Beats the Pandemic and Seeks New Growth

July 2, 2020

Paraguay acted forcefully against COVID-19 and succeeded in containing the pandemic with very few cases and casualties. But the economic impact has been harsh: GDP is forecast to shrink 5 percent this year. As it seeks to revive growth, the country is also undertaking reforms to improve governance and business climate.

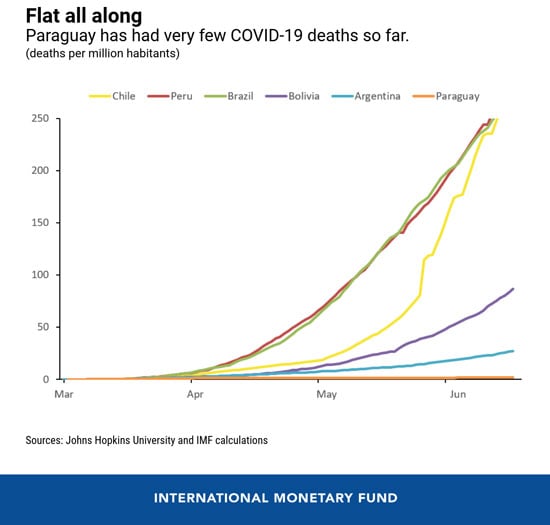

Nineteen people have died, out of around 2,100 cases, in a population of 7 million (about 2 people per million inhabitants). Neighboring Bolivia had more than 31,000 cases and over 1,000 casualties among its over 11 million inhabitants.

But the impact on the economy has been severe. In January we predicted growth of at least 4 percent this year, and there were signs that we were being pessimistic. With agriculture bouncing back from the drought and floods last year, it looked like economic growth would be strong in 2020. After a deep recession in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Paraguay had been growing at an average rate of more than 4 percent in the past 15 years, thanks to a boom in agricultural commodity prices and sound macroeconomic policies.

Then the pandemic hit. As in other countries, the lockdown hit economic activity severely. Consumption and investment plummeted. Imports of capital goods in April were 60 percent lower than a year before. Tourism and trade have similarly dried up. Our current GDP forecast for 2020 is -5 percent, but the exact depth of the recession is hard to predict.

The pandemic and the recession had a severe impact on Paraguay’s public finances, already weakened by last year’s drought, which doubled the deficit to almost 3 percent of GDP. While the plan earlier this year was to rein the deficit in, the COVID-19 onslaught made that impossible—and not desirable.

Spending on health care and social protection became urgent as lockdown measures hit people’s livelihoods.

Paraguay’s containment measures were effective, because the authorities acted fast and forcefully. The first COVID-19 case was known on March 7. By March 20, the country was in full lockdown, which lasted until May 3. The Ministry of Health used the time to ramp up testing and contact-tracing capabilities, allowing the country to begin a gradual reopening program (“smart quarantine”). While social distancing requirements have been eased, face masks are still mandatory in public, temperatures are measured at building entrances, and clients and employees must wash hands with disinfecting agents.

To help finance the higher fiscal deficit, Paraguay asked for International Monetary Fund (IMF) lending under the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI), designed to quickly provide assistance to countries hit by natural disasters or other shocks—like COVID-19. A $274 million loan was approved in late April and complemented by help from other international organizations.

What’s next?

Now that the economy is starting to reopen, it is time to think about the next steps. Paraguay has traditionally had good macroeconomic policies, with low deficits and debt, which has helped to avoid the boom-bust cycles of other countries in the region. These solid fundamentals will be important now as the country plots its future.

Once the economic recovery has strengthened, it will be important to restore the health of public finances. The deficit needs to go back toward the Fiscal Responsibility Law ceiling of 1.5 percent of GDP. How quickly will depend on the strength of the recovery. The country will have to find a balance between rebuilding its buffers and continuing to support its people and the economy.

To reduce the deficit, it will be crucial to have both effective spending and stronger revenues. Paraguay’s government revenue-to-GDP ratio is extremely low, about the same as in sub-Saharan Africa, and well below other emerging countries. Last year’s tax reform was a welcome first step, but more may be needed to mobilize domestic revenue.

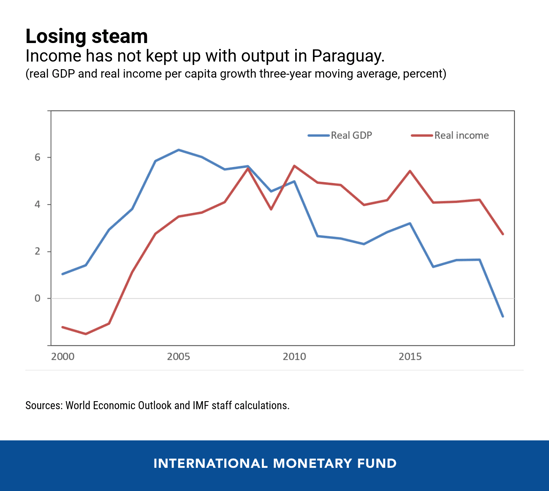

It will also be important to ensure that the income gap with rich countries continues to narrow. Even before COVID-19, Paraguay’s future growth was probably going to be slower than in the past 15 years, as some of the propellers of that growth (the boom in agricultural commodity prices and the rapid expansion of cultivated land) have lost strength. Real income growth was already slowing sharply compared to the 2000s, when it grew much faster than GDP, contributing to a rapid decline in poverty. That was explained by the rise in soy prices, which allowed the country to import more for each ton of soybeans exported. In recent years, the opposite has happened, causing poverty rates to fall more slowly.

Many countries manage to have strong growth spurts, but few succeed in closing that income gap. What is needed to achieve more convergence? Macroeconomic stability is a necessary but not sufficient condition. A recent IMF working paper argues that strong governance, good business climate and human capital can help poor countries achieve higher incomes faster. Paraguay scores poorly on these indicators, compared with most other emerging countries. The government is aware and acting on these challenges.

In early March, just before the lockdown, experts from the IMF and Inter-American Development Bank team visited the country to assess vulnerabilities to corruption. Their findings will help in developing a national strategy and action plan to combat corruption and improve governance.

And just a few days ago, the government announced an ambitious Economic Recovery Plan, which aims to address not only COVID-19 related near-term problems, but also longer-standing structural issues. For the near term, the plan seeks higher public investment (which helps employment); loan guarantees for informal and small enterprises (which addresses their financing problems); and social transfers to poor households (which will stabilize income and consumption). The plan also proposes important structural reforms, including civil service reform, a review of the fiscal responsibility law, administrative reform of the state, and better public procurement systems. All these reforms would help boost future growth in Paraguay and there are not many countries that have come up with such a holistic plan in response to the crisis.

When future economic historians look back at Paraguay in 2020, they will hopefully write that the COVID-19 crisis was the beginning of a period of profound reforms that set Paraguay on the road to a bright future.