Construction worker near Gdansk, Poland. Spending more on infrastructure can help CESEE countries support the COVID-19 recovery and raise potential output. (photo: KACPER PEMPEL/REUTERS/Newscom)

Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe After COVID-19: Securing the Recovery Through Wise Public Investment

September 28, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic is taking a sizable toll on the outlook for Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. The region is expected to contract by close to 5½ percent in 2020, erasing almost three years of economic progress. To support the recovery and improve living standards, countries could consider spending more on infrastructure, such as roads, schools, hospitals, and digital connectivity.

Related Links

Several countries are already planning to scale up public investment. Some will do so in the context of the Next Generation EU Recovery Fund: a strong display of EU solidarity, which will lead to very sizable transfers to EU countries in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Most of these funds are intended to be spent on investment under national recovery and reform plans. Making the most of this investment, while also accelerating the green and digital transition, will be more important than ever.

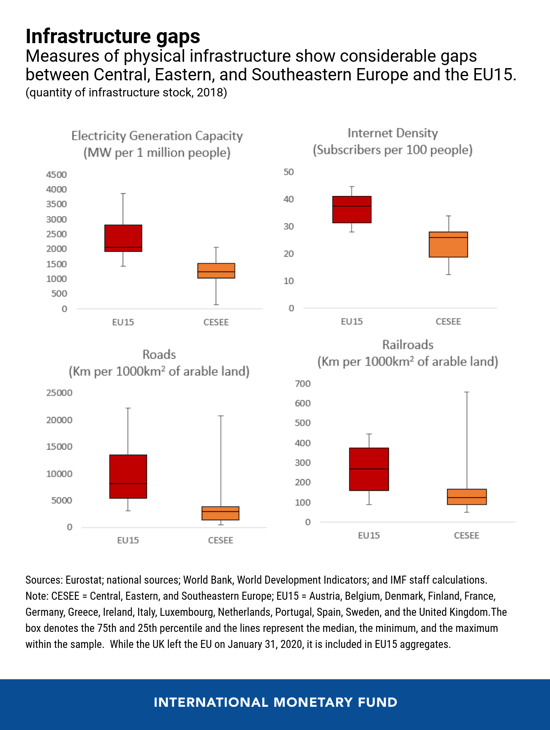

Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe is diverse, but the region lags far behind the more advanced European countries (EU15) in the quantity and quality of its infrastructure and regional connectivity (see box). Our new study finds that closing just 50 percent of the infrastructure gap with the EU15 by 2030 would cost between 3 to 8 percent of GDP per year.

Right time to boost infrastructure

If done right, infrastructure investment could yield significant dividends in the region. More and better public investment can help repair the economic damage of the pandemic, raise potential output, and speed income convergence with the EU15.

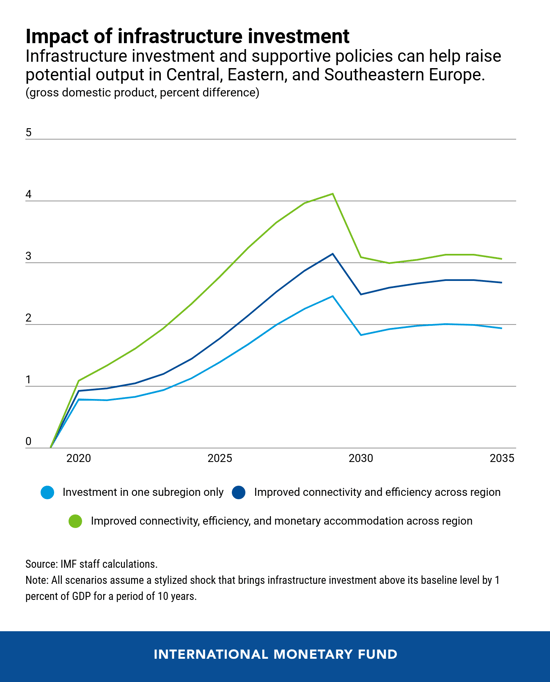

At this time of economic slowdown, its benefits could be even larger. We estimate that for each percent of GDP spent on infrastructure, output could rise by ½ to ¾ percent in the short run and by 2 to 2½ percent in the long run.

Strong governance of infrastructure projects and cross-country coordination can magnify these benefits. Our analysis indicates that the output dividends from scaling up infrastructure investment could be significantly higher with improved public investment efficiency and a focus on projects that improve regional connectivity and lower trade costs.

Managing fiscal risks

Nevertheless, these benefits will only be obtained if infrastructure projects are well managed. Supportive policies in the form of effective budget processes, procurement policies, and risk management are necessary complements to infrastructure investment.

As in many parts of the world, public projects in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe are often plagued by implementation delays and cost overruns, as revealed by our recent survey with country authorities. This mainly reflects poor governance. Detailed IMF public investment management assessments show that there is scope in the region to improve medium-term budgeting, project appraisal, selection, implementation, and procurement. Our recent survey also revealed gaps in fiscal risk analysis and management.

Strengthening infrastructure governance is not only key to realizing a better return on public investment but also to help mobilize private sector involvement, including Public Private Partnerships, and attract greater private financing.

Challenges brought on by the pandemic

The pandemic poses additional challenges to scaling up public investment. With a larger role for the government, opportunities for corruption may rise, especially when decisions on large-scale projects are made in a rush, without appropriate controls and accountability. Uncertainty about possible changes in the structure of the economy and the sharp rise in public and private debt may also weigh on the appetite for new infrastructure projects.

Governments should adopt a flexible approach. To better support the recovery, they need to reflect on changes in the economy and select projects with the highest growth dividend relative to the expected cost. For example, digital infrastructure is likely to see increasing demand, while other infrastructure sectors have less certain prospects. This may necessitate a review of priorities and capital spending, and an early identification of capacity and absorption constraints (for example, in procurement systems and access to capital, labor, and materials), and an even greater emphasis on value for money.

Focus on green and digital investments

Governments must also recognize that public investment programs create infrastructure that will shape carbon emissions and regional connectivity for decades. The cost-benefit analysis of any infrastructure project should include environmental considerations in view of the large economic impact of unmitigated climate change and its effect on infrastructure. Investing in climate-resilient and low-carbon infrastructure would help build the economy of the future. For EU countries, this will help achieve the EU climate goals, which the Resilience and Recovery Fund will support.

Countries should avoid locking in carbon-intensive activities, prioritize climate-smart technologies and practices, and seek to develop climate-resilience. Cost-benefit analyses should also take into account the gains from raising regional connectivity and trade, as output dividends could be significantly larger when projects are coordinated across borders.

The CESEE and EU15 regions

Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe (CESEE) includes Albania, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Kosovo, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Turkey, and Ukraine. During the past 30 years, these countries (except Turkey) have transformed from centrally planned into market-based economies, and since 2004, 11 countries have become members of the European Union. The more advanced European economies (EU15) include Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, which left the EU on January 31, 2020 but was part of the EU since 1993.