Memorial Lecture in Honor of the Late Professor Emmanuel Tumusiime-Mutebile

January 27, 2023

Introduction

Mr. President, honorable ministers and governors, distinguished guests, all protocol observed (as I learnt to say here in Uganda):

Thank you very much Acting-Governor Michael Atingi-Ego for your generous introduction and indeed kind invitation to give this lecture.

I am very honored to be here amongst you all today. All the more so given the occasion—a celebration of the late Governor Emmanuel Tumusiime-Mutebile.

I have though to also admit to being a bit intimidated. Many of you have known him for much longer and worked with him much closer. But perhaps an outsider’s perspective is no bad thing for such an event.

If I may, I would like to start by explaining my association with the late Governor. I met him first in 2006, when I moved to Kampala to work as Resident Representative of the IMF. But I knew of him and his work well before that as his personality and policy perspectives would often come up in discussions on how the IMF should engage with developing countries. The 3 years I spent here, I got the opportunity work with him fairly closely and learn a great deal from him. Our acquaintance hence forged, I continued to benefit immensely from our engagements since then through many interactions from afar, in Washington, and on my visits here.

Given the range of issues that the late Governor has worked on during his distinguished career as a policy maker, when Acting-Governor Atingi-Ego asked me to give this lecture I had to think quite a bit what to focus on. I settled on what issues Governor Mutebile would have focused on to help Uganda and indeed other Africa countries navigate through the current rather difficult global economic conjuncture and mounting geopolitical tensions.

The rest of my intervention is accordingly structured as follows. I will start by setting out the global and regional context in particular. I shall then highlight the evolution of key development indicators in Uganda, with a particular emphasis on how the country compares with its peers. And playing of this, I will highlight three policy priority areas to reinvigorate Uganda’s development progress—something of course the Governor dedicated his whole life to. I will finish with a few concluding thoughts.

Regional and Global Context

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, extensive economic fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, synchronized and marked tightening of global financial conditions, heightened macroeconomic imbalances are back with vengeance as the first order economic challenge in many countries around the world, and notably so here in Africa.

The ways these imbalances are presenting themselves and their extent varies from country to country. But in the broadest of terms, the imbalances can be seen via:

- Surging inflation. For the most part, this is because of spillovers from international developments—reflecting the sharp increases in international food and fuel prices, what with hindsight has proved to be rather aggressive counter-cyclical fiscal stimulus by advanced economies, and Covid-induced supply chain disruptions. Take Uganda, inflation at end-2022 stood at 10.2 percent, this compares with 2.9 percent at end-2021 and 2.4 percent at end-2019 on the eve of the outbreak of the COVID19 pandemic.

- Acute debt pressures. The level of public indebtedness across the world has gone up markedly in recent years. This reflects a range of factors, including: (i) relatively easy financing conditions, which at least for a while, facilitated higher safe debt levels; (ii) the adverse balance sheet effects of major global shocks, notable the recent COVID-19 pandemic which, particularly in Africa, markedly impacted economic and developmental outcomes; and (iii) development spending needs.

- Constrained financing. A corollary to mounting debt pressure and, indeed, a factor that has contributed to these pressures is the marked increase in the cost of financing facing most African countries. This is a much-overlooked point. Take Uganda. Through 2005 or so, official development assistance, a non-trivial share of which was channeled through the budget, was in the range of 12 to16 percent of GNI each year. This contrasts with just 6 percent of GNI between 2015 and 2019. The effect of this has been to raise the weighted average cost of financing facing most countries, as countries have not filled the gap via revenue mobilization as much as they have by expensive market financing domestically and externally. And at the current juncture, access even to this has become curtailed.

- Pressure on exchange rates. As the major central banks have tightened monetary policy aggressively to contain inflation, the cost of borrowing abroad—an importance source of financing for countries in recent years—has risen markedly. Indeed, in many cases, it has not just been a case of capital inflows abating, but rather capital outflows. The strong pressures on exchange rates and foreign exchange reserves is thus not surprising.

I should also here add that it is not just economic headwinds that emerging and developing countries are facing but also geopolitical tensions which are beginning to hamper closer global integration. Specifically, geo-political fragmentation—an ongoing phenomenon amplified, though not generated, by the war in Ukraine—has started to disrupt trade and investment flows, dislocating global value chains, and raising production costs. Globalization over the last several decades has been a powerful phenomenon that has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and impacted Africa beneficially. If, as it is threatening to, globalization goes into reverse, it will compound the current economic difficulties.

The last time we had a constellation of this kind of economic and geopolitical headwinds facing developing countries was probably the 1980s and early 1990s. When I mentioned this to a colleague the other day, she said that I was overlooking the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09. But I think the effects of that Crisis were more limited in most African countries because of the region’s then limited financial integration with global markets. More important, countries debt levels were manageable so many countries were able to pursue supportive counter-cyclical policies to limit the sharp slowdown in Advanced countries. Not so this time.

There are many, many reasons why we all miss the late Governor. One of them is because I would so much have liked to get his wise counsel as to how to navigate through the current rather difficult economic landscape.

Some Stylized Facts on Uganda’s Development Progress

For this next bit of my intervention, I want to ask you to cast your minds back to 1990. To my mind, policymakers here in Uganda and indeed elsewhere in the region faced three major challenges: (i) getting growth started; (ii) sustaining high growth for decades; and (iii) engendering structural transformation. How have outcomes fared on this count?

Getting growth started was first task and was achieved relatively quickly. Ugandan policymakers moved aggressively to limit macroeconomic imbalances. High inflation was recognized for the awful distortionary tax it is on the poor. An important contributor to high inflation had been excessive monetary financing. This was addressed by better aligning public spending with available financing. Consequently, inflation decelerated quite rapidly. Annual inflation which averaged 149 percent in 1988-89 was reduced to some 6 percent a decade later.

As important as the initial steps to contain macroeconomics imbalance though were the frameworks, institutions that the late-Governor was instrumental in helping put in place to ensure that imbalances remained contained on a sustained basis. First, while Permanent Secretary/Secretary Treasury at the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, he helped introduce the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework. This helped set out the envelope for spending in the current and forthcoming budgets, made transparent the trade-offs that were being made between spending categories, and helped set expectations for line ministries. Second, once he moved the Bank of Uganda, he was relentless in ensuring that the Bank kept inflation in check. Initially, this was via more of a rules-based approach—annual targets for monetary growth. But as the link between monetary targets and inflation outcomes became less robust, he pushed for the adoption of an inflation-targeting lite approach. These innovations may sound rather technical and boring, but I can assure you they were the basis through which macroeconomic stability was assured and it was on this foundation that growth was sustained.

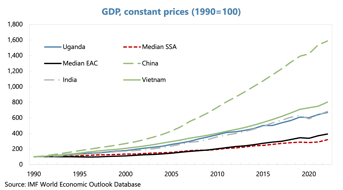

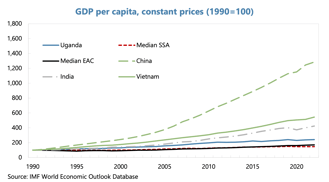

The second challenge, sustaining sufficiently high growth for decades, has been the more difficult feat for developing countries. But it is a challenge that Uganda has accomplished rather successfully. Between 1992 and 2011, Uganda’s real GDP growth of 7 percent per year on average was almost double the median sub-Saharan African or East African Community (EAC) growth rate. Uganda’s performance in those years was impressive even compared with the Asian success stories of India and Vietnam. Growth has slowed a bit over the past decade, with Uganda falling behind its Asian peers, it still outperformed the median sub-Saharan African country. High population growth over this same period, however, meant that the gains were less rapid in per capita terms. Specially, between 1992 and 2011, whereas per capita income increased threefold in Vietnam, it increased just twofold in Uganda. Still, I do not want to diminish Uganda’s achievement. Sustaining growth such uninterrupted growth for a landlocked country with the security challenges that prevail in some neighboring countries is a commendable feat.

How well has Uganda fared in engendering structural transformation? This is the process whereby an economy transforms from being a primary-commodity based economy to one where industry and services dominate economic activity and where productivity increases markedly. Such transformation is the kernel of economic development.

The picture on this front is more mixed. Through around 2011, there was significant progress in this dimension, but this has lost steam and even reversed in some cases since around then. Let me cite some numbers at you, if I may:

- The share of industrial activity increased from 10 percent in 1990 to 27 percent in 2021 in Uganda, with most of the increase taking place during the first two decades of this period. While the pace of transformation was much higher than in the median SSA or EAC country, the current level of industrialization is not much different from Uganda’s regional peers. Similarly, the share of services increased from 30 to 42 percent between 1990 and 2021 in Uganda. The past decade, however, has seen some reversal. Currently, the share of services is lower than in the median SSA country.

- The transformation of the economy was also reflected in the greater integration of the Ugandan economy with the rest of the world: export volumes grew four-fold from 2000 to 2020. At the same time, a large compositional shift in the export basket towards manufacturing occurred during the first two decades of the period, which has since been partly reversed in the past decade.

What accounts for the initially rapid progress and subsequent stalling of economic transformation in Uganda? To my mind, three factors are at work:

For one, some of it no doubt has to do with a generally observed phenomenon in the process of long-run development across countries, whereby growth and transformation tend to be faster in the initial stages and mature to a more moderate pace as per capita income rises.

Second, I would venture, however, that there are other contributing elements, notably from the external front. The global environment was generally more supportive of frontier market growth in the 1990s and 2000s as China’s rapid growth and integration into the international economy generated favorable spillovers.

Finally, my strong sense is also that the overarching approach to policymaking in Uganda—very much characterized as Adam Smith put it by, peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice—is not sufficient for engendering structural transformation, at least not rapidly so. A much more deliberate, sustained, and focused approach is needed. Playing defense, with the occasional and random attacking forays—that is, the way Manchester Unite played against Arsenal last week—no longer suffices (as United found out also). Mr. President, forgive me for going a bit off script, but there are some on this podium who actually support United and some other teams.

Policy priorities for the next stage of the development process

Moving to the current conjuncture, what might have the late Governor Mutebile settled on as the reform priorities, to re-invigorate structural transformation.

First and foremost, I think he would have called for much more domestic revenue mobilization. Let me make the case for this as I think he would have—very directly:

- For one, the government has much spending and investment to undertake and alternative financing sources are scant.

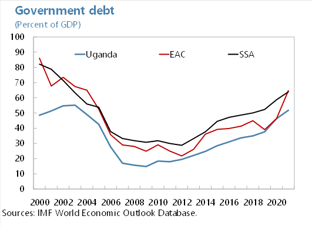

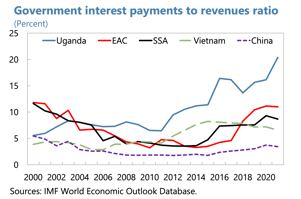

- Second, Uganda is doing rather poorly in terms of revenue collections relative to its peers and the amount of debt that needs to be serviced. As a share of GDP, tax revenue collection is below 15 percent—much lower than the EAC average, much less what is observed in other developing countries. And this shortcoming becomes even more obvious when we compare the ration of interest payments to tax revenues: in Uganda it currently stands at 20 percent, compared to 11 percent on average in the EAC, and 9 percent on average for SSA. When you compare the level of debt in Uganda with other countries, it does not stand out because public debt as a ration stands at around 50 percent, markedly below the 64percent SSA average. But in terms of debt servicing capacity, Uganda clearly is doing less well.

It is for this reason that I strongly believe that the late Governor would have focused like a laser beam on revenue mobilization as a priority challenge. This is not something that requires not just technical solutions like—improving tax administration or eliminating tax exemptions—but also quite a lot of political will. One of the most impressive things about being an occasional traveler to Kampala is how much the skyline, infrastructure, and nature of business activities continue to transform remarkably between visits. It is clear that, facilitated by strong public delivery of infrastructure services, in particular, businesses are making a lot of money. And rightly so. But the government is not doing a good job capturing the returns through taxes on all of the investments it has been making over the years. I know that one concern is more revenue collection will deter activity. But as I noted above the level of taxation here is much below the threshold where higher tax collections could disincentive investments. Besides, if spending is not going to have to be squeezed further and/or the fiscal deficit widen, there is no alternative to further increasing tax collections.

The second priority that the late Governor would have identified I think is the importance of further human capital investment for climbing up the value-added ladder. In Uganda, both secondary and tertiary school enrollment have been lower than in SSA and well below the level in emerging Asian countries. Also, in the context of the recent school closures during the pandemic, learning loses have been significant and minimized the risk of children not returning to schools. This is particularly important now as Uganda begins to experience a rising demographic dividend with the working-age share of the population set to increase in coming decades. Fully reaping the benefits of this dividend will require investing in the skills of the working age population to enhance their employment prospects.

The third policy priority is financial sector development. I know from conversations that I have had with him that limited progress in financing deepening was a source of deep disappointment. The most telling number in this regard I think is the rather low level of credit to the private sector as a share of GDP. The average in sub-Saharan Africa is 40 percent. In Uganda, 14 percent of GDP! Just about one-third of the sub-Saharan Africa average. Why does this matter? Why has financial deepening disappointed?

It matters because the process of structural transformation requires the movement of labor and capital from one part of the economy to another. And this in turn requires new investment by firms and economic agents. Often in the early stages of development, this tends to be financed through retained earnings and profits. This constrains the amount of resources at their disposal. But with access to bank lending and financial markets, the scope for investment increases. If these markets are however malfunctioning, the process of moving investment to higher productivity activities also suffers.

To my mind, two reasons dominate why financial deepening has stalled in Uganda. For one, the reform agenda in this area never really went much beyond interest rate liberalization and bank privatization. There could have been much more aggressive follow up to identify the binding constraints on credit intermediation and addressing them as tends to be the case in many other countries. One argument I have heard to explain the dearth of lending in Uganda is that the cost of borrowing is to high. But I once heard the late Governor refute this point by pointing out that there are many other countries where the cost of credit is as high but banks undertake much more lending.

Second, financial markets do not work in isolation. Perhaps more than any other business activity, the financial sector requires a transparent and effective judiciary for contract enforcement, robust bank supervisory and regulatory frameworks, and active weeding out of ineffective and weakly capitalized entities. Gone are the days when informal and personal relations could facilitate this. Rather, in this environment what is needed are robust mechanisms and institutions that can reassure economic agents to transact with each other knowing well people that transgressions will be penalized. Again, these issues while are partly technical, but given the vested interests that stand to be affected it is something that requires a whole-government approach and political will to enforce.

Part IV: Conclusion

Let me wrap up with a few thoughts.

First, I want to outline what I consider to be the late Governor’s overall approach to policymaking—a deep appreciation for human fallibility. I think this is why throughout his distinguished career he championed the need for: institutions that promote excellence and good governance, frameworks that set the limits and require trade-offs, and to pay heed to market signals. I think this is an approach that is very much still applicable today. On my occasional visits here, I have sensed frustration in government circles that development is not progressing rapidly enough and something radical must be done. This frustration is one I share because the potential of this country is second to none. But as I hope I have been able to persuade you, what is needed is a focus on a few key areas: revenue mobilization to promote resilience, further investment in health and education, and financial sector deepening. You have here an economy that has been able to continue expanding for a remarkably long time. It is important to not jeopardize this. What is needed now is upgrading the capacity of the state to engender more rapid structural transformation. Not unlike computers, the modern economy requires continuous software upgrades as glitches and vulnerabilities emerge. This requires talented and empowered officials in key policymaking positions to continuously work on identifying and alleviating constraints to growth and investment.

Second, I of course need to say something about the late Governor’s persona. He was as brainy as they come as an economist and policy maker—with very strong analytics, whiplash smarts, and always open to powerful counter-arguments. As well, he was incredibly courageous. I have previously described him as a “lion of a policymaker”. This is of course in reference to his lifetime of public policy service at Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, Bank of Uganda, and his contributions to the East African Community, that have left a large and illustrious imprint on policymaking and policymakers throughout the region and beyond. But it is also in reference to his fearlessness—the way he stood his ground when he felt policies detrimental to progress were being considered. He was always ready to speak truth to power. And mind you, he was doing this even in the days when doing so risked very real personal harm. I think there is much that our generation of policymakers, advisors, technocrats could do to emulate him. We have to of course recognize that policy positions are often adopted as much for political reasons as they are solely for economic ones. An important way we can pay homage to the incredible success and legacy of people like the late Governor Mutebile is by making sure we compellingly make the case for the appropriate course of action and laying out the consequences of failing to pursue it.

Finally, and as the occasion calls for, I have centered my remarks around the late Governor Mutebile. The humble, generous, and often shy person that he was, he would probably have been a bit mortified by the sole focus on him if he was with us today. I think he would have wanted recognition of his very able fellow collaborators, the likes of the late Chris Kassami and Keith Muhakanizi. I also bow my head to them and many others that have so ably served the Ugandan people.

Thank you.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER: Nicolas Mombrial

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org