The Role of Inflation Expectations in Monetary Policy

May 15, 2023

Inflation expectations are an important factor in monetary policy decisions. And with actual inflation far off target in many countries around the world, there has been an increased focus on inflation expectations and whether they remain anchored. Today I would like to discuss which expectations matter for policymaking, in terms of the various groups—forecasters, markets, households—who form expectations, as well as the different—near- or longer-term—time horizons. More specifically, in the current period, should central banks feel comfortable that inflation will return to target because long-term inflation expectations seem well-anchored? Or should more emphasis be placed on short-term inflation expectations, which have seen considerable increases?

Inflation expectations were not always considered a relevant input into the policymaking process. To better understand the role of expectations in monetary policymaking, and to answer the questions posed, it is useful to first go back in time and look at a brief history of the role of inflation expectations. I will then turn to summarizing some of the evidence suggesting expectations matter for the inflation process and monetary policymaking.

Arguably, monetary policy has an important role in ensuring that inflation expectations for different groups and horizons stay well-anchored, so I will touch on the different dimensions of that role, including the importance of strong monetary policy frameworks.

Before concluding, I will turn to the current conjuncture, briefly discussing the current state of inflation expectations.

History of the role of inflation expectations

Historically, central banks did not always care about inflation expectations. In the context of the original Phillips curve, in which nominal wage growth was linked to unemployment, there was no mention of expectations—or inflation for that matter. In 1960, Samuelson and Solow introduced a modified price-inflation Phillips curve for the United States. Because of the clear and stable trade-off between unemployment and inflation in their modified price-Phillips’ curve, this was interpreted as something of a “menu” of inflation/unemployment options; policymakers could pick whether they were more concerned about inflation or unemployment. An expansionary policy could lower unemployment at the cost of a fixed, and controlled, amount of inflation.

The empirical performance of these original Phillips Curves deteriorated starting in the mid-1960s and into the Great Inflation period of the 1970s and early 1980s. Economists initially found the combination of high inflation and high resource slack hard to reconcile with the supposed tradeoff between those two, although in 1975 Robert Gordon explained how a “supply shock” modifies the Phillips curve to allow for such “stagflation” (Blinder, 2022).

The poor performance of the static Phillips Curve during The Great Inflation period generated interest in other explanations. Phelps and Friedman argued (independent from each other) that inflation expectations mattered. Any deviations from the natural rate of unemployment would shift the short-run Phillips curve up or down. An unemployment rate below the natural rate of unemployment would increase inflation expectations, thereby shifting the short-run Phillips Curve up. As such, the increase in inflation from a lower unemployment rate was not finite but would accelerate as long as the unemployment rate was lower than its natural rate.

This had two key implications. Contrary to earlier beliefs, there was no permanent tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. Furthermore, in more general terms, it galvanized interest in how inflation expectations matter for both aggregate supply and aggregate demand.

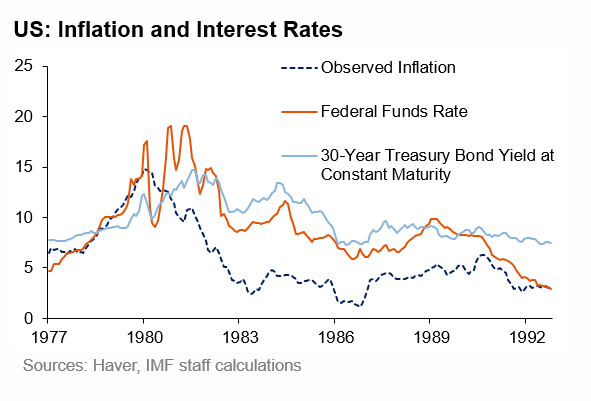

By the time Paul Volcker took the seat as Fed Chair, central banks were devoting increasing attention to long-run inflation expectations. Yet in the absence of good measures of inflation expectations, these were imperfectly proxied by long-term bond yields. Assuming away risk premia, increases in the yields of 10-30y treasuries were interpreted as increases in long-run inflation expectations.

As long-term yields had moved from roughly 4 percent in the early-1960s to nearly 20 percent by the late-1970s, this was viewed as a clear sign that long-run inflation expectations had de-anchored. High long-term inflation expectations were a symptom of central banks’ low credibility in delivering price stability.

Weak anchoring was also recognized as hurting policy effectiveness and the central bank’s ability to conduct countercyclical policy. It was therefore viewed as critical to re-anchor the system by reducing long-term inflation expectations through tight monetary policy.

The graph depicts the development of inflation along with the fed funds rate and the long-term bond yield for the period that is often referred to as the “Volcker disinflation.” What is striking is that observed inflation fell much more quickly than long-run inflation expectations, as proxied by long-term bond yields. This suggested that monetary credibility took a long time to be regained.

The Fed was reluctant to ease policy until long-run inflation expectations had come down significantly. This is also clear from the graph. While inflation falls quite sharply in the early 1980s already, the federal funds rate stayed higher for much longer.

During the 1980s, the Fed responded to subsequent “inflation scares” by aggressively tightening policy. Inflation scares are indicated by rapid jumps in long-term nominal yields. The takeaway was that monetary policy could influence long-term inflation expectations—and hence inflation—through persistent policy actions.

Long-run inflation expectations in today’s policymaking

To this day, central banks remain very attentive to ensuring that measures of long-run inflation expectations (market and survey-based) remain near their targets, and for good reasons. These measures provide a key signal of central bank policy credibility. They are also critical for monetary policy transmission through financial market channels. Moreover, they are typically viewed as important in affecting short-term inflation dynamics. Even now, central bank models, such as the FRB model for the US economy, focus on long-run inflation expectations.

As an aside—although the earlier examples mostly illustrate central banks’ concern with long-run inflation expectations becoming too high, there have of course also been concerns about long-run expectations becoming too low. Specifically, in the period following the Great Financial Crisis, central banks were very concerned that a fall in long-run inflation expectations would reduce current inflation and compress policy space. But the recent inflation surge has put at least a temporary stop to such worries.

While long-run inflation expectations are clearly critical for policy, there remain several open questions. In the current period, should central banks feel comfortable that inflation will return to target because market-based long-term inflation expectations remain well-anchored? Or are there other dimensions of inflation expectations that matter for inflation determination and monetary policy transmission?

To focus on the latter question before turning to the former, one might simply ask, “What else matters besides long-run market-implied expectations?”

Other measures of inflation expectations can be important in understanding inflation and wage dynamics, as well as policy transmission through aggregate demand. And these other measures can be grouped in a number of dimensions. Of particular importance are shorter horizons, which matter most for actual inflation both in theory and in practice. In addition, we should also consider different economic agents, such as households and firms.

We know that firms’ inflation expectations are relevant for investment, hiring, and price-setting decisions (Gorodnichenko & Coibion, 2018). And households’ inflation expectations have been shown to be relevant for consumption, saving, home-ownership, and financing decisions (Andrade et al., 2020; Duca-Radu et al., 2021), and they feed into wage negotiations and labor supply decisions. One can also examine patterns of interpersonal disagreement and heterogeneity of beliefs concerning inflation (Andrade et al., 2019).

Today I will delve a bit deeper into the latter two: household expectations and heterogeneous beliefs, or distributions of expectations.

Household expectations—a closer look

For a long time, household inflation expectations were generally not regarded as a particularly useful input into monetary policy decisions due to their often volatile and dispersed nature. But the use of survey expectations—and particularly those of households—improves the empirical performance of the New Keynesian Phillips Curve. And it turns out that the dispersion of household expectations is actually quite informative.

If we were to look at the recent evolution of the distribution of household inflation expectations for selected large economies, we would see that changes in the distribution of household expectations contain information about future inflation.

An IMF working paper, which is to be released soon, examines household survey micro-data for Canada, Germany, the US, and the UK and demonstrates that there are potentially meaningful shifts in the distribution of expectations—and these shifts are often not captured by changes in the mean or median expectations.

This recent work at the Fund suggests that there can be important signals embodied in these shifts. Indeed, changes in the distribution of one-year-ahead household expectations serve as a predictor of one-year-ahead inflation, and they provide additional insight relative to the information available from market and professional forecasts.

The literature also finds that household expectations can help to explain inflation, including the recent surge. Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Kamdar’s paper in the Journal of Economic Literature argues that the use of survey expectations, and those of households in particular, resolves some notable shortcomings associated with the New Keynesian Phillips Curve under the assumption of full information “rational” (model consistent) expectations. Prominent amongst these shortcomings are the model’s under-prediction of inflation during the Great Recession (Coibion and Gorodnichenko, 2015), its relatively poor forecasting record (Faust and Wright, 2013), and a thorny set of econometric issues that complicate both estimation and inference (Mavroeidis et al., 2014).

The use of survey expectations improves the New Keynesian Phillips Curve’s empirical performance, but also introduces a theoretical inconsistency. The curve’s specific form rests on the assumption of rational expectations, which does not hold with survey data. If you drop the rational expectations component, you also lose the microfoundations of the New Keynesian Phillips Curve.

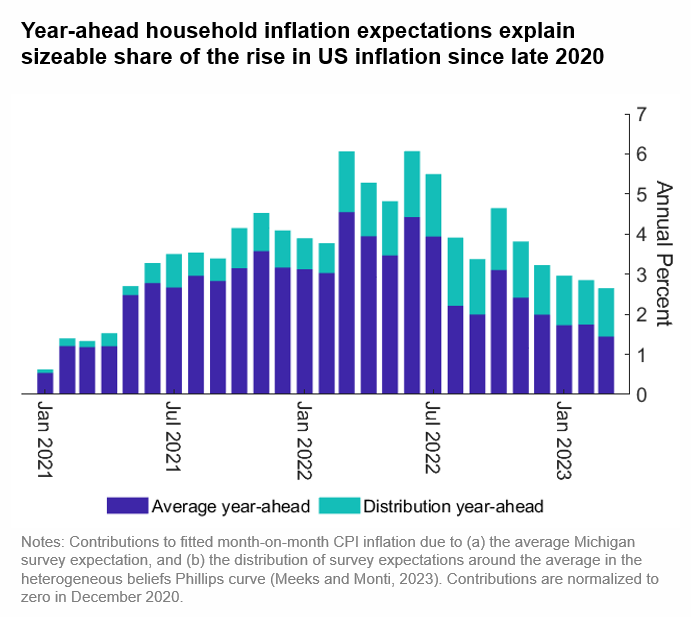

To help resolve this inconsistency, Meeks and Monti (forthcoming) derive a Phillips curve with non-rational expectations and show how to estimate it with survey data. The signature feature of their model is that the heterogeneity present in beliefs about future inflation—as summarized in the distribution of inflation forecasts made by different agents—matters for the determination of current inflation. They show that the adverse effects of higher average expected inflation can be reinforced when expectations are dispersed and skewed to the upside, as in the post-Covid period depicted in the graph.

Household expectations may also affect demand. Higher inflation expectations have been shown to increase consumption, as confirmed in the literature. Research published earlier this year found positive inflation expectations increase the marginal propensity to consume for durables. It was found that households expecting stable prices have a lower propensity to buy durable goods than those expecting positive inflation. In contrast, differences across households expecting positive inflation are associated with insignificant differences in durable consumption decisions.

Household expectations may further matter for saving and/or investment decisions, according to the evidence from the expectations literature. When examining the effect inflation expectations might have on households’ homeownership decisions, it has been found that people with high-inflation experiences subsequently have higher inflation expectations, and that this increases their preference for buying versus renting a house (Malmendier and Wellsjo, 2020). Through a similar mechanism, inflation expectations might affect households’ financing decisions, for example when they need to choose whether to pay fixed or floating interest rates on their mortgage (Malmendier and Nagel, 2016; Botsch and Malmendier, 2021).

For labor supply decisions and for wage setting, recent analysis shows that short-term household inflation expectations are relevant for the wage Phillips Curve. Moreover, the effect of inflation expectations on labor supply and the wage-setting process are potentially both regime-dependent (Rudd, 2021). This is so because when inflation is low and stable, it probably does not play an integral role in one’s decision to change jobs, or change the amount of hours one works. Hence, in such a situation there is little effect of expectations on labor supply and wage negotiations. However, when inflation is persistently high, it might affect people’s cost of living so much so that it becomes an important factor to consider when negotiating a wage, or deciding on hours worked.

If household expectations affect realized inflation through supply and (more importantly for monetary policy) demand, this is clearly relevant for monetary policy. But to understand how monetary policy can effectively influence this, it is important to understand how households form expectations.

A large body of literature shows that inflation expectations are not very responsive to central bank communication. It seems that, generally speaking, communication about decisions, or instruments used, does not effectively reach households. If anything, households respond mostly to information related to the inflation target (Coibion et al., 2022).

A recently growing body of literature suggests that (personal) experiences matter a lot for how people form inflation expectations. On the one hand, experiencing a period of high aggregate inflation has a long-lasting effect on people’s inflation expectations (Malmendier and Nagel, 2016). On the other hand, one’s personal exposure to specific price changes matters. The effect that personal exposure to price changes has on one’s inflation expectations is, for instance, greater for frequently-purchased grocery items, and for increases in the prices of items purchased, versus price drops (D’Acunto et al., 2021a, 2021b).

These experiences also affect professionals, such as firm managers. In fact, even expectations of FOMC members are affected by their personal experiences with (high) inflation: Henry Wallich dissented 27 times during his tenure on the Fed board 1974–76; he lived through the German hyperinflation (Malmendier et al., 2020).

Implications for monetary policy

Returning to the earlier question of whether policymakers should pay attention to long-run or short-run expectations, the answer is an unequivocal “yes” on both counts. Above all, they provide important signals of policy credibility. Credibility is important for effective policies. Referring again to The Great Inflation, in the 1980s inflation came down faster than long-run expectations, but it took many steep rate hikes to get there.

Currently, long-run inflation expectations seem to have remained fairly well anchored. But should expectations de-anchor, bringing down inflation could be much more painful. Therefore, central banks also need to consider the impact of shorter-term expectations on inflation dynamics.

Market-based inflation expectations remain elevated, as is evidenced by the current one-year inflation swap rates. Short-term household expectations also remain high. But in the most-recent data, short-term inflation expectations for the US and the Euro area are coming down.

However, the decline in household inflation expectations significantly lags those of market participants. This gap raises the interesting question of whose expectations matter for real interest rates? With high household inflation expectations, implied real rates for households might be lower than those estimated for markets. The consequence could be an effectively easier monetary policy stance than we tend to assume based on market expectations, and a more muted effect on aggregate demand.

What should monetary policy do?

When inflation stays persistently high, there is an increasing risk of expectations de-anchoring. If the experience of inflation has such an important effect on expectations, it can be dangerous for central banks to let inflation run high for too long—irrespective of the source of high inflation.

Because household inflation expectations are more responsive to price increases than cuts, it may take more time to bring inflation expectations down than it would for them to rise. It also appears that people are relatively inattentive to inflation, unless they are in a high-inflation regime. Hence, ending up in such a regime could make both inflation and inflation expectations much more persistent.

At the same time, central bank communication efforts may be a relatively ineffective way to influence inflation expectations of firms and the general public. They often get their information on inflation from sources other than the central bank, mostly television and newspapers. Therefore, there is all the more reason for a central bank to act swiftly and keep a tight stance so as to bring actual inflation down quickly and minimize the experience of high inflation.

Current evidence suggests that there are still some risks of a de-anchoring. In this environment, monetary policy frameworks themselves are also important. Inflation expectations are lower in countries with strong monetary policy frameworks; hence, central banks need to build and maintain strong policy frameworks.

Strong policy frameworks are backed by a robust set of laws governing the central bank and its operations. These define and shape the central bank’s independence and accountability. Equally important are the manner and practice of the central bank in carrying out the design, implementation, and communication of monetary policy.

Conclusion

Inflation expectations are an important factor in monetary policy decisions. And with actual inflation far off target in many countries around the world, there has been an increased focus on inflation expectations and whether they remain anchored. Central banks should not presume that inflation will return to target simply because long-term inflation expectations seem well-anchored.

While long-run inflation expectations are clearly critical for policy, other measures of inflation expectations are important in policy transmission. For example, short-term household expectations serve as an important additional predictor of inflation. As such, central banks should place more emphasis on short-term inflation expectations, which have seen considerable increases.

The experience of high inflation can have lasting effects on expectations, so it is critical not to allow inflation to remain elevated for too long. In the current environment, risk management considerations therefore call for a continued tight policy stance.

IMF Communications Department

MEDIA RELATIONS

PRESS OFFICER:

Phone: +1 202 623-7100Email: MEDIA@IMF.org