Reimagining Social Protection

New systems that do not rely on standard employment contracts are needed

The changing nature of work is upending traditional employment and its benefits. In developed economies, global drivers of disruption—technological advances, economic integration, demographic shifts, social and climate change—are challenging the effectiveness of industrial-era social insurance policies tied to stable employment contracts. Those policies have delivered formidable progress, but they have also increasingly harmed labor market decisions and formal employment.

Such systems in rich countries were developed at a time of widespread "jobs for life," with social insurance based on mandatory contributions and payroll taxes on formal wage employment. This traditional, payroll-based insurance system is increasingly challenged by working arrangements outside standard employment contracts.

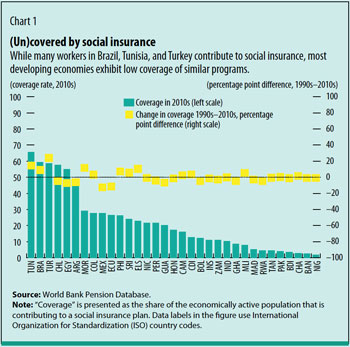

In developing economies, the world of work has mostly been diverse and fluid. Hence, the uniformity and stability of work that underpins traditional social insurance systems may not hold. In fact, social insurance participation and coverage have remained low. In Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Pakistan, which account for about a third of the world’s population, the number of people covered hovers around a single digit, with virtually no change in decades (see Chart 1).

Technology’s impact on work

Although quantifying the impact of technological progress on job losses continues to challenge economists, estimates abound. The bottom line is that technology is changing how people work and the terms under which they work. Instead of once-standard long-term contracts, digital technology is giving rise to more short-term work, often via online platforms. These so-called gigs make certain kinds of work more accessible and flexible. More widespread access to digital infrastructure—via laptops, tablets, and smartphones—provides an environment in which on-demand services can thrive.

It is difficult to estimate the size of the gig economy. Where data exist, the numbers are still small. Worldwide, the total freelancer population is estimated at about 84 million, or less than 3 percent of the global labor force of 3.5 billion.

Informality persists on a vast scale in emerging market economies—as high as 90 percent in some low- and middle-income countries—notwithstanding technological progress. Because recent technological developments are blurring the divide between formal and informal work, there is a convergence in the nature of work between advanced and emerging market economies. Labor markets are becoming more fluid in advanced economies, while informality persists in emerging markets. Most of the challenges faced by short-term or temporary workers, even in advanced economies, are the same as those faced by workers in the informal sector. Self-employment, informal wage work with no written contracts or protections, and low-productivity jobs more generally are the norm in most of the developing world. These workers operate in a regulatory gray area, with most labor laws unclear on the roles and responsibilities of the employer versus those of the employee. This group of workers often lacks access to benefits. There are no pensions, no health or unemployment insurance programs, nor any of the usual advantages provided to formal workers.

This type of convergence is not what was expected in the 21st century. Traditionally, economic development has been synonymous with formalization. This is reflected in the design of social protection systems and labor regulations. A formal wage employment contract is still the most common basis for the protections afforded by social insurance programs and by regulations such as those specifying a minimum wage or severance pay. Changes in the nature of work caused by technology shift the pattern of demanding worker benefits from employers to demanding welfare benefits directly from the state.

A new social contract

The original purpose of social protection systems remains: to prevent poverty, cover catastrophic losses, help households and markets manage uncertainty, and ultimately provide a foundation for more efficient and equitable economic outcomes. These objectives motivated the architects of the "welfare state," as it has come to be known, and should both motivate and guide efforts to keep social protection systems relevant and responsive.

New systems are needed that serve the needs of all people, regardless of how they engage in the market to make a living. These new policies must also be more adaptable and resilient to dynamic economic, social, and demographic forces. In other words, a new social contract is needed.

As we examine the changing nature of work (World Bank 2018), we must take a closer look at how to better protect people and workers in the new economy. These are some key findings:

Informality, the share of the population not participating in traditional social insurance and related protections, is currently about 80 percent of the labor force in developing economies. This is a major bottleneck to extending protection. Most workers, especially the poor, are engaged in informal sector activities with little or no access to social protection. Given the endemic nature of this challenge and minimal progress against it, most people would be better off with a social protection system that does not depend on their work situation.

Social assistance, which contributes to equity in societies, could be enhanced. There are several options. At one end of the spectrum is a means-tested guaranteed minimum income program, which distributes cash to households, with benefits gradually declining as income rises. At the other end is universal basic income, with unconditional cash transfers to all, independent of income or employment. Both are distributed monthly.

An intermediate option is a negative income tax—a way to provide money to people below a certain income level—with a relatively high threshold and a gradual withdrawal of benefits. Since a negative income tax is woven into the tax declaration cycle, it tends to be paid annually. Another such option could be a smaller guaranteed minimum income supplemented with other programs, such as universal child allowances and social pensions. The cost of such an arrangement depends on the level of benefit, scale of coverage, and shape of the income distribution graph. But increasing robotization could reduce fiscal constraints, and this type of benefit may become important for social as well as economic stability.

For informal economies, greater ability to identify individuals and households and monitor their consumption—if not income—opens new possibilities at the nexus of universal basic income, negative income tax, and guaranteed minimum income, or even a negative consumption tax. Targeting would be based on proxy indicators for unobserved income from special surveys and identified by linking administrative databases.

The notion of "progressive universalism" (Gentilini 2018) may help guide expansion in ways that benefit the poor and vulnerable first. The principle recognizes that universality in itself does not necessarily make the poorest better-off than existing provisions. Hence, as countries expand social protection toward universality, the most vulnerable should be given priority, special attention, and adequate support.

In addition, the global architecture of social protection as set out by United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 1.3 aims to "implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors." Similarly, strategic partnerships such as the International Labour Organization–World Bank Universal Social Protection Initiative help elevate universality as a strategic goal for countries and organizations supporting them.

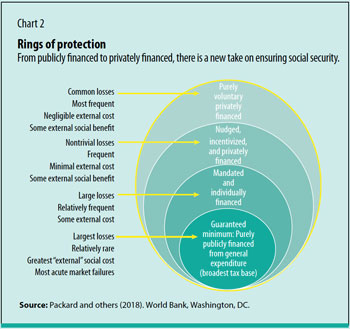

The key issue is the need for a more neutral policy stance than many governments currently take with respect to the factors of production and to where and how people work. Once basic protections are guaranteed, people could upgrade their security with various progressively subsidized programs—mandatory contributory insurance and savings plans where feasible and an array of voluntary options where the state and markets can offer them (Packard and others 2018).

The once politically convenient mingling of social objectives—risk pooling, poverty elimination, and the pursuit of equality through wealth redistribution—calls for more explicit distinction and different risk-sharing arrangements and financing channels. To prevent people from falling into poverty, for example, the largest and most effective risk pool is a country’s national budget. Ideally, decisions about financing alternatives would follow consideration of the appropriate policy instrument to deploy (risk pooling, saving, or prevention) and the proportionate policy response given what is privately available. A stylized package of protection against losses from livelihood shocks is illustrated in Chart 2.

The innermost core represents the guaranteed minimum support needed to cover the most catastrophic losses with the greatest social costs—such as livelihood disruption that plunges families into poverty—for which there are no viable or effective market alternatives. Ideally, but not always, these incidents are relatively rare. Interventions to cover more frequently occurring, lower-loss events—for example, structural churn in the labor market and retirement—but with obvious and substantial external social benefits, could be included in this guaranteed minimum support program. In the three remaining rings, responsibility for financing and provision gradually shifts away from purely public resources and direct provision to household or individual financing and market provision.

Is leapfrogging possible?

Technological change, one of the global drivers of disruption in the world of work, also offers opportunities for governments to move away from, or leapfrog over, prevailing industrial-era policies and to offer more effective risk sharing to citizens and residents.

India’s Direct Benefit Transfer, an innovative use of digital technology to provide direct subsidies to the bank accounts of the poorest, is a powerful example of what is already possible. In Ghana, the Labor Intensive Public Works programs digitized paper-based transactions and made wide use of biometric machines. The result was a reduction in payment time from four months to a week.

The World Bank is currently investing $15.1 billion in delivery systems and related technology. Platforms such as social registries, IDs, and payment mechanisms are making it possible to reach excluded populations. For example, about 75,000 girls and women in rural Zambia can now choose whether to receive digital payments through a bank, mobile wallet account, or prepaid card. In West Africa, a foundational ID platform aims to cover 100 million people regionally by 2028. And in Indonesia, a cash transfer program has reached 10 million poor households, expanding to the remote eastern corners of the archipelago to meet human development goals.

Faced with an imperative to adopt new policy models, the lowest-income countries have an advantage: low effective coverage of industrial-era risk-sharing policies means greater opportunity to leapfrog into a more modern social protection system. As with telephony and financial services, the limited coverage of legacy models makes new approaches easier for countries to embrace.

The investments by many countries to develop the capacity and systems to better identify households, assess vulnerability and poverty, and deliver cash transfers more efficiently are critical assets that make the policy ideas proposed here a real possibility.

Together we can shape the future of social protection in ways that ensure broad gains for all, and for the poorest in particular.

ART: ISTOCK/ALASHI

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.

References:

Gentilini, Ugo. 2018. "What Lessons for Social Protection from Universal Health Coverage?" Let’s Talk Development blog, World Bank, August 22.

Kuddo, Arvo, David Robalino, and Michael Weber. 2015. " Balancing Regulations to Promote Jobs: From Employment Contract to Unemployment Benefits." World Bank, Washington, DC.

Packard, Truman, Ugo Gentilini, Margaret Grosh, Philip O’Keefe, Robert Palacios, David Robalino, and Indhira Santos. 2018. "On Risk Sharing in the Diverse and Diversifying World of Work." Social Protection and Jobs White Paper, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Rutkowski, Michal. 2018. "A Glimpse into the Future of Social Protection." Let’s Talk Development blog, World Bank, August 24.

World Bank. 2018. World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work. Washington, DC.