Typical street scene in Santa Ana, El Salvador. (Photo: iStock)

IMF Survey : Study Examines Banking Vulnerabilities’ Impact On Public Debt

March 19, 2015

- Bank vulnerabilities can foreshadow big costs for government budgets

- Pre-crisis bank characteristics, crisis management policies matter

- Better information, fiscal policy, tax policy can limit banking stress effects

IMF staff has identified several features of countries’ banking systems that can amplify the effects of banking sector vulnerabilities on the government, and ultimately the fiscal costs of banking crises.

When booms bust, fiscal pressures are worse in banking recessions than in normal credit cycle downturns (photo: Tibor Bognar/Photoshot/Newscom)

BANKING CRISES

While the 2008 global financial crisis highlighted the far-reaching implications of the linkages between banks and the central government for public debt sustainability, these linkages are not new, a new study notes.

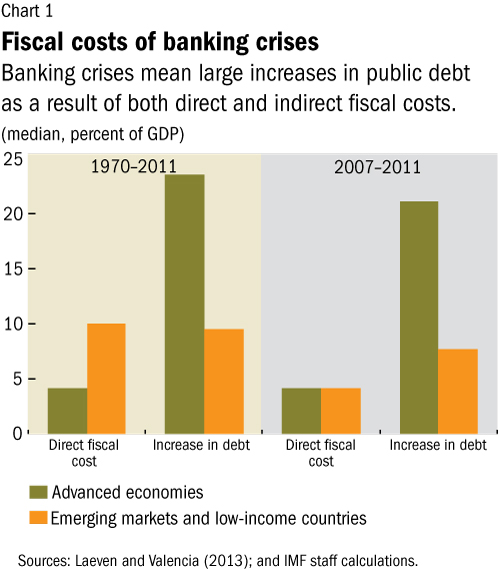

Over the past three decades, banking crises have contributed to large increases in public debt (see Chart 1). The median cost of direct government intervention in banking crises was 7 percent of GDP. Including indirect fiscal costs from post-crisis recessions, the median increase in public debt four years after the beginning of a crisis was 12 percentage points of GDP. And in many countries, public debt increased by more than 20 percentage points of GDP.

“While sound regulatory and macroprudential policies are the first line of defense, governments should be prepared for risks that inevitably remain,” noted Said Bakhache of the IMF’s Strategy, Policy, and Review Department, one of the report’s authors.

Fiscal cost of bank vulnerabilities

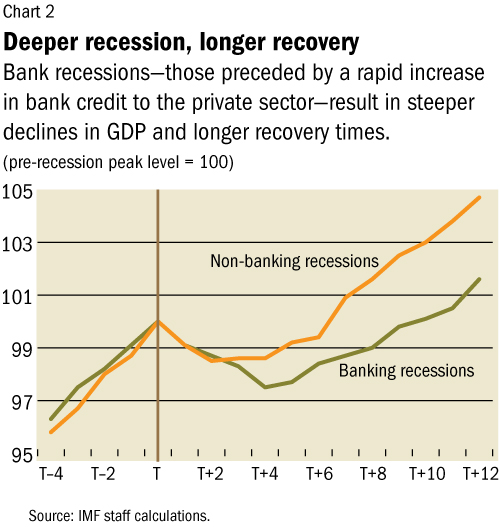

“Banking recessions,” or recessions preceded by a rapid increase in bank credit to the private sector, tend to exhibit deeper contractions in GDP and longer recovery times than other recessions (see Chart 2). And while banking expansions boost fiscal balances during an economic boom, once the boom turns to bust, fiscal pressures are significantly worse in banking recessions compared to recessions associated with more normal credit cycles. This leads to greater deteriorations in the fiscal outcomes and public debt.

When large banking expansions unravel in systemic banking crises, public finances tend to take a significant hit. The high direct fiscal costs of crisis management policies, particularly bank bailouts, are amplified by the overall economic impact of the banking crisis: risk premia rise, consumption and investment fall, and asset values suffer.

These effects compound to reduce government revenues and create public spending needs, potentially leading to rapid buildup of public debt. The impact on public debt is lessened somewhat by asset recovery, which has been high in some countries.

Factors that affect the bank-sovereign link

Several features amplify the effects of banks’ vulnerabilities, the study says.

• Banks’ balance sheet expansion, leverage, and reliance on wholesale external funds are found to be positively associated with the depth of subsequent recessions, length of recovery, and the fiscal costs of banking crises.

• Pre-crisis institutional settings and crisis resolution policies play an important role--for example, better banking supervision and broader deposit insurance coverage tend to reduce the direct fiscal costs of banking crises, while the provision of bank guarantees after the onset of the crisis is associated with greater direct fiscal costs.

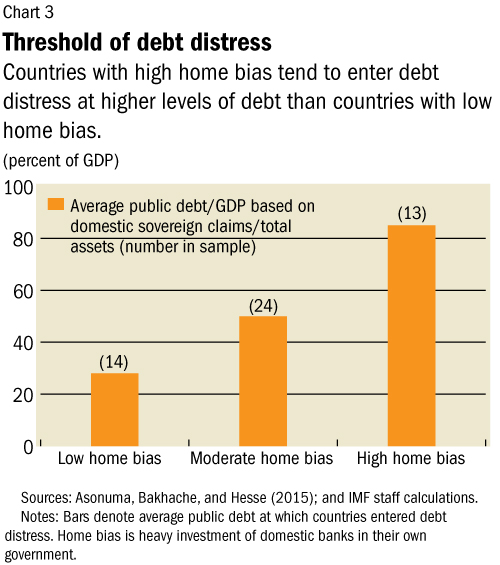

• Heavy investment of domestic banks in their own government—also known as “home bias” —amplifies the link between banks and the sovereign. Although such “home bias” can help reduce borrowing costs and provide fiscal space, especially during times of stress, it can also create incentives for countries to postpone fiscal adjustment until the stock of debt reaches very high levels. Moreover, countries with high home bias tend to enter debt distress at higher levels of debt than countries with low home bias (see Chart 3).

Monitoring of fiscal risks from the banking sector

A survey of IMF member countries reveals that, although countries have made improvements in the management of fiscal risks in the wake of the global financial crisis, gaps remain in how they monitor and assess the transmission of risks from banks to the government. Countries often only make such assessments when stresses are already imminent.

These gaps can potentially undermine the authorities’ ability to anticipate the fiscal impact of crises, and hence to take pre-emptive measures. To limit the fiscal repercussions of banking stress, the study recommends that countries establish a framework for routinely sharing information on banking risks among the relevant agencies, while preserving their operational independence, and for monitoring key indicators that can signal heightened fiscal risks from banking sector vulnerabilities, including potential contingent liabilities.

The study also examines the case for public reporting of such risks. It suggests that this would help inform public discussions and build support for reforms, so long as adequate precautions are taken to address moral hazard and confidentiality issues.

Additional lines of defense

The authors conclude with recommendations that can lessen the risks and impact of banking vulnerabilities.

• Fiscal authorities should “lean against the wind” and build up buffers during banking booms that can be used in the case of a downturn.

• Debt managers should consider the tradeoffs in relying on domestic banks as a financing source for the government; and

• Governments can reduce tax incentives that encourage debt over equity financing, helping to decrease excess leverage and supporting ongoing regulatory efforts to increase banks’ equity capital.