Financial regulation hasn’t caught up with risks posed by big tech firms; it’s time for a policymaker rethink

Large technology companies such as Alibaba, Amazon, Google, and Tencent—“big techs”—are coming under policymakers’ spotlights, and political momentum is growing for new competition and antitrust legislation. As big techs expand their financial offerings, these efforts are particularly relevant for financial authorities: the current regulatory framework could fail to contain the risks these new business models bring to the financial sector. A new policy approach is needed that takes into account the unique features of big techs—such as their vast scale, ample customer base, and access to large amounts of data—and captures the risks from the significant interconnection among different entities within a big tech group and the broader financial system (Crisanto, Ehrentraud, and Fabian 2021).

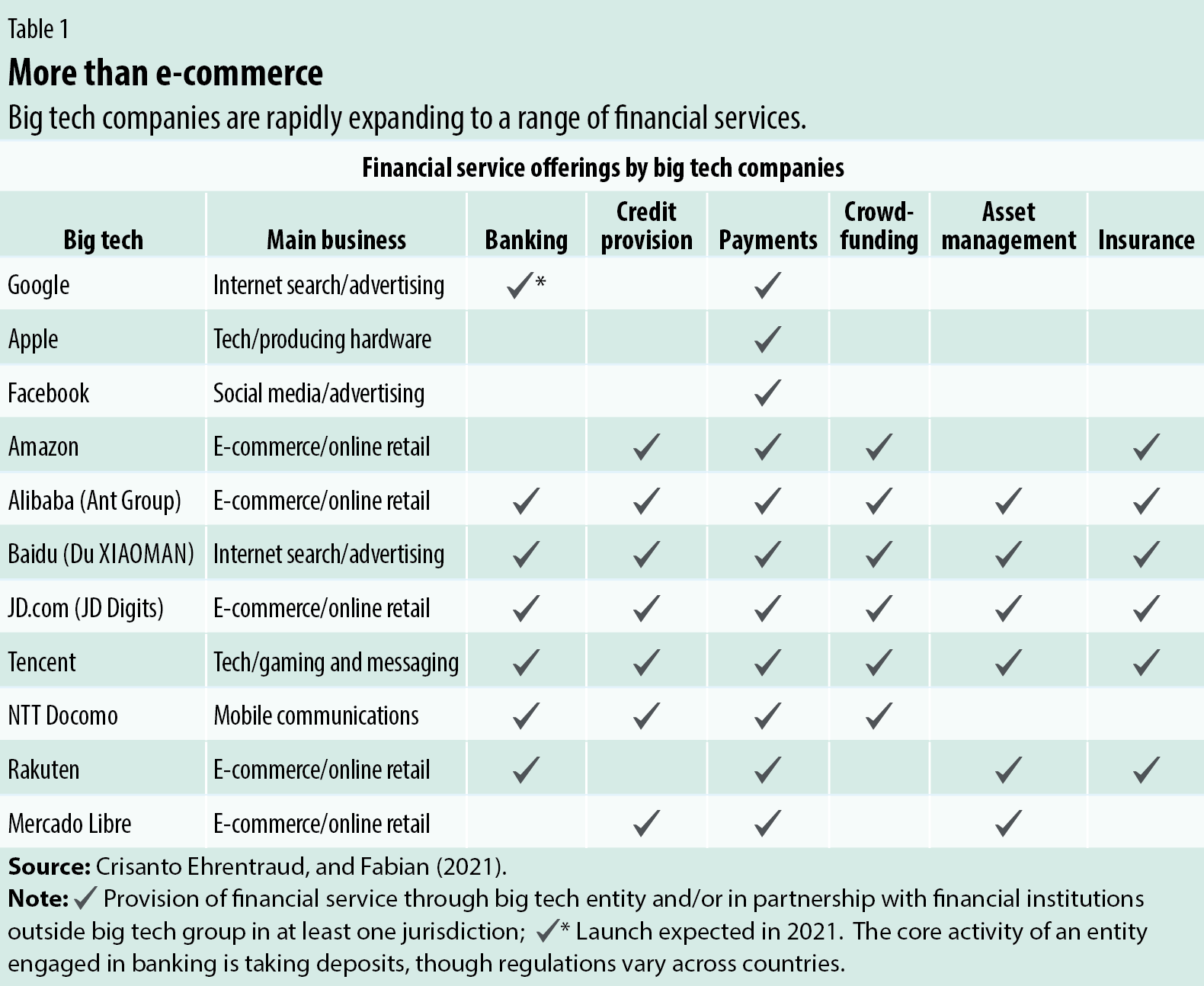

Big tech’s involvement in finance started with payments, and they now have a substantial market share in some countries. In China, for example, big tech firms had by 2018 already processed payments equivalent to 38 percent of GDP (FSB 2020). They soon expanded to other sectors, such as credit provision (particularly consumer financing and microloans with shorter maturities), banking, crowdfunding, asset management, and insurance (see Table 1). Geographically, big techs’ expansion into financial services has been more pronounced in emerging market and developing economies than in advanced economies for several reasons. One reason is that less financial inclusion in emerging market and developing economies may increase demand for big tech services, particularly by unbanked and underserved populations (FSB 2020).

A varied and growing presence

Big techs provide their financial services either in competition with traditional financial institutions or in partnerships that use existing products and infrastructure. Some big techs provide only the customer-facing interaction. Others also hold minority stakes in financial institutions outside their groups.

Financial services still play a small role in these companies’ business models, but this could change rapidly—for four reasons:

The network effect: Once a big tech has attracted a sufficient number of users, network effects kick in, accelerating its growth and increasing returns to scale. Every additional user creates value for all the rest. The more users a platform has, the more data it generates. More data, in turn, provide a better basis for data analytics, which enhances existing services and thereby attracts more users (BIS 2019).

Gatekeeping: Significant network effects may enable big techs to become gatekeepers for certain types of services. This may include control over who can enter the market, who receives what kind of data, and how the market operates. This allows them to leverage their dominant position in a given market to exert influence over its functioning.

Captive users: With a large and captive user base built through extensive customer networks and coupled with the low cost of acquiring customers over the internet, big techs can scale up quickly in market segments outside their core business. For example, it took money market fund Yu’e Bao 20 months to reach 100 million users; Ant Financial’s Sesame Credit got there in only 11 months (Citi GPS 2018).

Technological investment: Big techs devote significant resources to developing and acquiring state-of-the-art technologies, particularly data analytic capabilities. After all, access to large troves of data generates value only if it is matched by the ability to analyze it. Research and development (R&D) spending of big techs dwarfs that of many banks. For example, the annual average R&D spending (2017–19) by JPMorgan Chase was $11 billion, compared with Amazon’s $20 billion. Amazon, Apple, and Google now account for 3 of the global top 10 companies by R&D expenditures (IBFed and Oliver Wyman 2020).

The regulatory landscape

With the newcomers knocking at the gates, financial authorities are seeking a balance that supports big techs’ benefits while minimizing their potential risks to the financial system. Although the overall impact of big techs’ entry into financial services is still unclear, these firms have the potential to make the financial sector more efficient, improve customer outcomes, and aid financial inclusion. This may, however, put financial stability and consumer protection at risk and presents challenges for competition, data privacy, and cyber security.

Big techs operating in finance are already subject to a combination of specific financial industry regulations that apply to banking, extending credit, and transmitting payments and to general laws and regulations on data protection and competition.

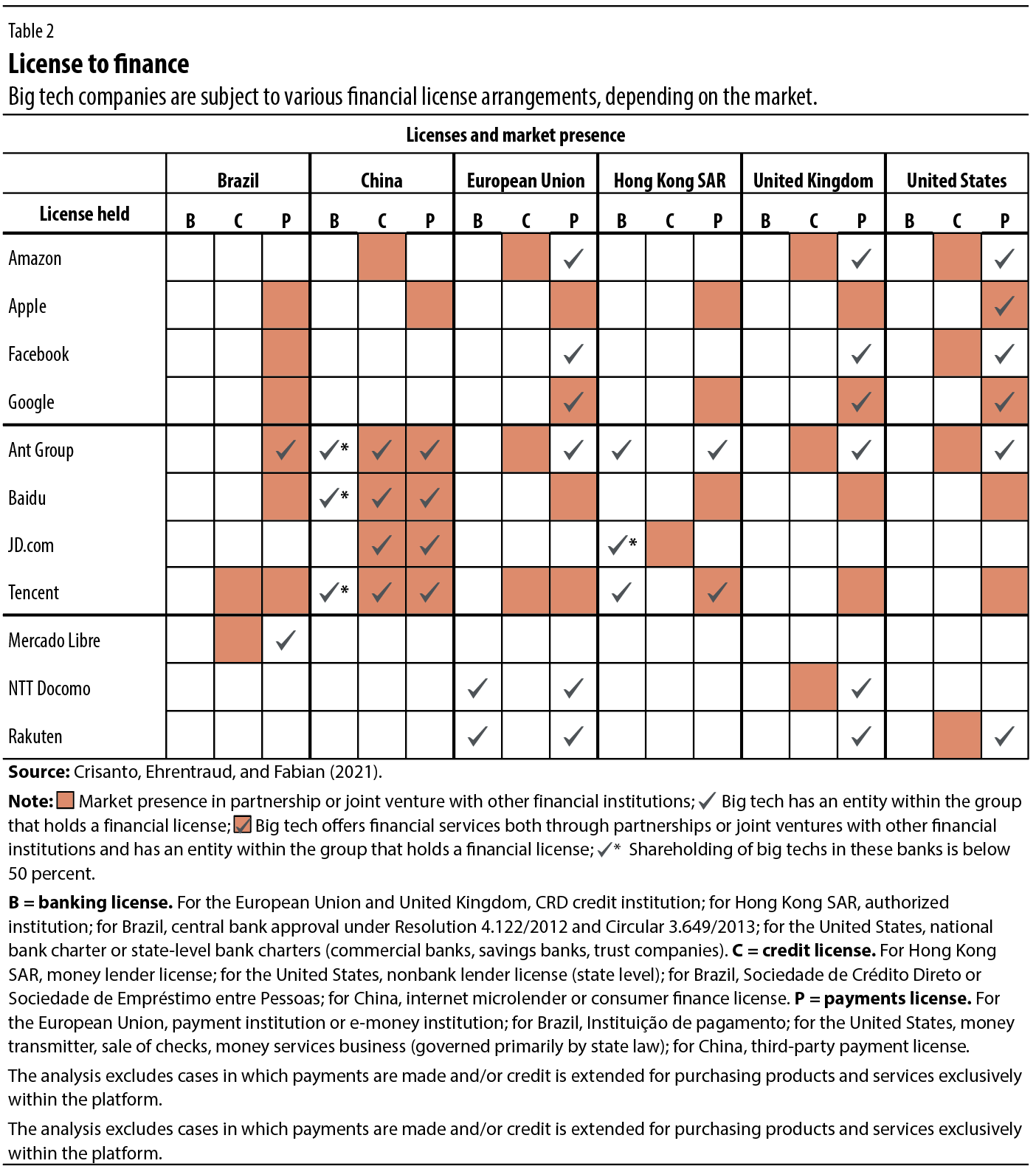

Big techs and their subsidiaries that provide financial services must hold the appropriate licenses for specific regulated activities. Big techs that provide financial services through partnership or joint ventures with financial institutions, however, do not usually need licenses.

With respect to cross-industry regulations, jurisdictions take different approaches to banks, nonbank financial institutions, and nonfinancial entities, including those within big tech groups. Broadly speaking, even where these types of entities face exactly the same requirements, they may be subject to different levels of supervision of their business practices. Finally, depending on the national setup, there could be a multitude of authorities responsible for enforcing cross-industry regulations, each with its own mandate and policy objectives.

Of 11 big techs that provide banking, credit, and payment services in different regions, 4 have majority-owned entities in their group that hold banking licenses; none, except in China, are licensed to grant credit (without taking deposits), but operate in partnership with other institutions; and all have entities in their group that hold payment licenses in at least one jurisdiction (see Table 2).

Risks not fully captured

The current policy approach around the globe does not pay due attention to the unique features of big tech business models and the corresponding risks. Finance-specific and cross-industry regulations are geared toward individual legal entities within big tech groups for the particular activities they perform. The business model of big techs, however, involves a variety of services provided under a wide range of modalities, which be tough for policymakers.

Financial authorities may struggle to understand and stay current with big techs’ continuously evolving business models. Meeting this challenge calls for a clear picture of the services big tech entities provide both locally and across borders (including as service providers to financial institutions), how these services are offered (for example, through partnership with other financial institutions or their own licensed entities, or as “matchmakers”), and how big techs monetize data. The lack of transparency of big tech groups and the multitude of regulators overseeing different aspects of big tech operations just make things more complicated.

A second set of hurdles involve the unique characteristics of big techs, which typically include numerous group entities. These perform highly interrelated activities, making it particularly difficult for authorities to assess their risk profile. Three types of risk stand out:

- Partnerships with incumbents can dilute accountability and promote excessive risk-taking when big techs provide only the customer-facing layer of the value chain and do not bear any underwritten risks themselves. Without any skin in the game, big techs may be less inclined to screen and monitor clients, and the interests of big techs and the financial firms involved may not be fully aligned.

- A big tech group has many different entities that depend on each other in different ways. A problem in one part of the group can stir up trouble for another part if contagion and reputational risks materialize.

- Financial stability risks can arise from the concentration and dependence on critical third-party services, such as data storage, transmission, and analytics, big tech companies provide to other financial institutions, particularly in the context of a cyber event or operational failure.

A third group of challenges has to do with the current financial framework’s ability to respond swiftly and effectively to big techs rapidly becoming systemically important, even in areas where their operations appear relatively modest at present.

A new policy approach for big techs

The risks posed by big tech business models are not comprehensively dealt with under the existing financial regulatory framework. Authorities may decide to enhance the current framework and consider the following policy options:

- Recalibrating the mix of entity-based and activity-based rules: An activity-based regulation can complement, but not replace, entity-based regulation. Different types of institutions may generate different risks when performing the same activity. Big tech business models involve a bundle of very different activities—e-commerce, payments, cloud services—each of which gives rise to a specific set of interrelated risks. The characteristics of big techs matter for how they should be regulated, and developing more entity-based rules for big techs in specific regulatory areas, such as competition and operational resilience, seems prudent (Carstens 2021; Restoy 2021).

- Introducing a bespoke policy approach for big techs: The unique features of big techs may warrant a comprehensive public policy approach that focuses not only on individual big tech entities and their activities but also on how individual big tech entities work together in the background to provide services to their customers on the big tech platform. Such a specialized approach must establish objective criteria that qualify a firm as “big tech”—which could prove difficult given their differences—and monitor and mitigate the systemic component resulting from the combined activities of a big tech firm. More information on big tech groups is mission-critical to achieve these goals. Enhanced disclosure of financial and nonfinancial information would give authorities a comprehensive understanding of their domestic and cross-border operations; the nature and extent of the risks involved; and the links between entities within the group, external financial institutions, and the financial system as a whole.

- Enhancing local and international supervisory cooperation: In light of the cross-sectoral and cross-border nature of big tech activities, increased emphasis on cooperation and coordination at the local and international levels is imperative. Cross-sectoral and cross-border cooperation between national authorities—including at the very least financial, competition, and data protection authorities—would be a practical step in this direction.

It’s time for policymakers to rethink the current policy approach. This includes contemplating a comprehensive public policy approach that better integrates financial regulation with competition policy and data privacy. It’s been said that it’s better to build a fence at the top of a cliff than have an ambulance waiting at the bottom. Now is a good time to consider what that fence should look like.

References:

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). 2019. Annual Economic Report, Chapter III, Basel.

Carstens, A. 2021. Introductory remarks at the Asia School of Business Conversations on Central Banking webinar, “Finance as information.” Basel, January 21.

Citi GPS. 2018. “Bank of the Future: The ABCs of Digital Disruption in Finance.” Citi GPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions (March).

Crisanto, J. C., J. Ehrentraud, and M. Fabian. 2021. “Big Techs in Finance: Regulatory Approaches and Policy Options.” FSI Briefs 12 (March).

Financial Stability Board (FSB). 2020. “Big Tech Firms in Finance in Emerging Market and Developing Economies.” Basel.

International Banking Federation (IBFed) and Oliver Wyman. 2020. “ Big Banks, Bigger Techs? How Policymakers Could Respond to a Probable Discontinuity.” New York.

Restoy, F. 2021. “Fintech Regulation: How to Achieve a Level Playing Field.” FSI Occasional Paper 17, Financial Stability Institute, Basel.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF and its Executive Board, or IMF policy.