It is time to consider significant reforms to the way the Olympics are pursued, prepared for, and hosted

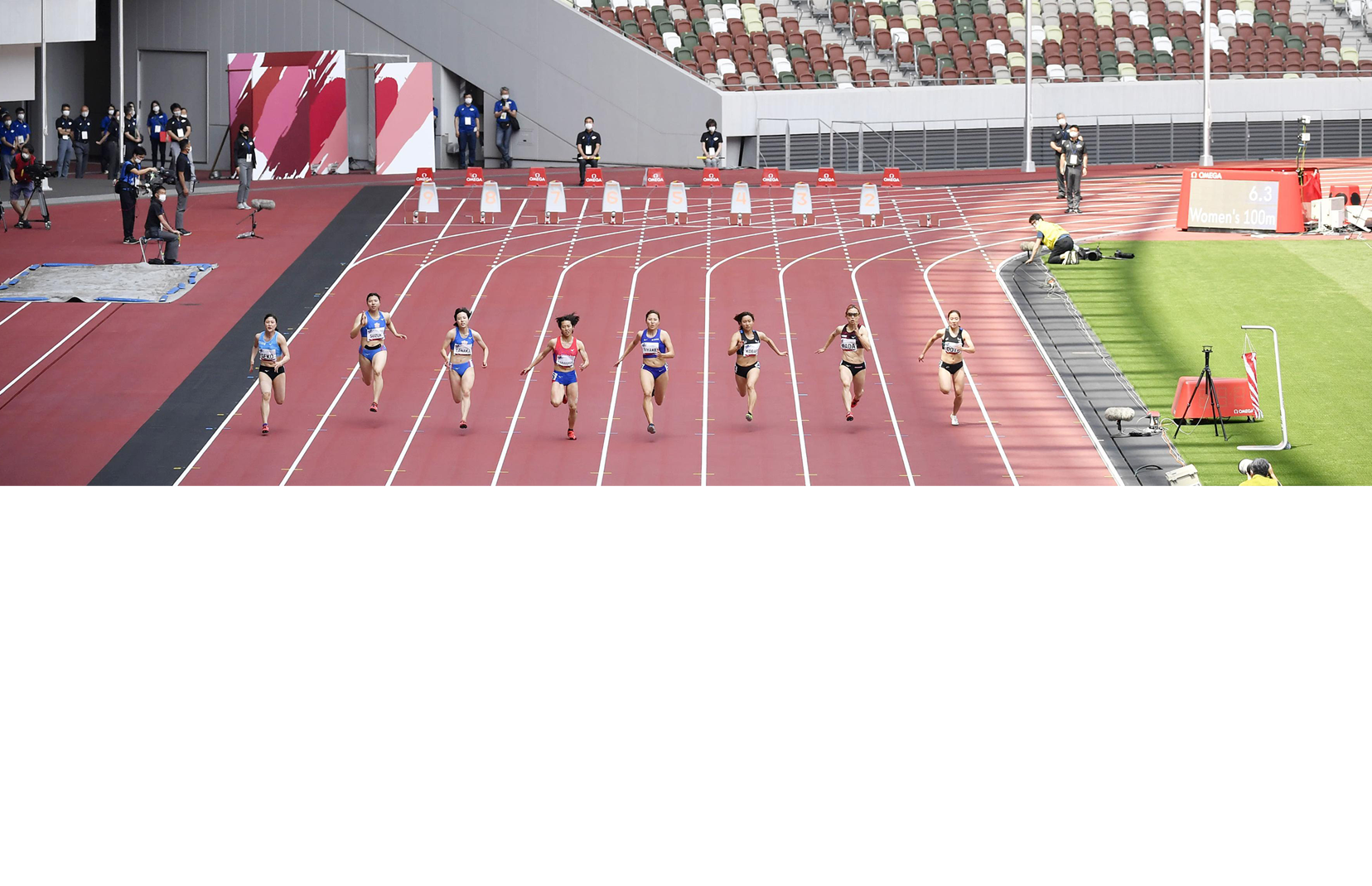

When Tokyo won the right to host the 2020 Summer Olympics back in 2013, it was seen as a great honor and an opportunity to showcase the city to the world. Celebrations rang out in the streets of the Japanese capital as the city began to prepare to host the event for the first time since 1964. But the golden sheen has worn off the coming games. The Japanese government has declared a state of emergency because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which will result in most events being held without spectators, and a majority of Tokyo citizens now want the Olympics delayed or canceled altogether. It is tempting to say that Tokyo is simply a victim of bad luck related to the ongoing global pandemic, but even before COVID-19 struck, forcing the one-year postponement of the games, the Tokyo Olympics were already suffering from massive cost overruns and were well on their way to being one of the most expensive on record. With the cost of hosting the games now routinely exceeding any reasonably expected returns, it is time to consider significant reforms to the way the Olympics are pursued, prepared for, and hosted, including possible permanent Olympic venues around the world.

For 125 years, the modern Olympic Games have highlighted the peak of human athletic endeavor as reflected in the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC’s) motto—“Faster, Higher, Stronger.” Host cities have gladly shared the spotlight with the world’s greatest athletes at the world’s premier athletic event, and for many years, cities competed as vigorously as the athletes themselves for the perceived honor of hosting the quadrennial Summer or Winter Olympic Games. The past decade, however, has witnessed growing popular backlash against the Olympics worldwide as exploding costs and increasingly uncertain benefits accruing to the host city have significantly dampened interest in staging the games. Without significant changes, the IOC may find itself with few partners willing to undertake the risk and expense.

From rather humble beginnings in 1896, the modern Olympics quickly took on significance beyond simple athletic competition, and as the scale of the Olympics grew, so did the cost to the host city. With a price tag of more than $500 million (in 2021 dollars), Adolf Hitler’s 1936 Summer Games in Berlin, which were clearly designed to highlight the power and dominance of Nazi Germany, were not only 10 times more expensive than any previous games, they cost Germany more than every other previous host combined (Matheson 2019).

The 1936 games set a bank-breaking precedent, but it was only the first of many modern games that spent money faster and raised costs higher, but didn’t leave economies stronger. For example, despite Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau’s famous claim that “The Olympics can no more lose money than a man can have a baby,” that city’s 1976 Summer Games’ massive cost overruns set a dubious new record, costing nearly $7 billion, a record that has been shattered many times since. All five of the most recent Summer Olympics and both of the most recent Winter Games have exceeded $10 billion in total costs; the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics topped $45 billion, and the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics exceeded $50 billion (Baade and Matheson 2016).

These cost figures typically compare unfavorably with revenue projections. Revenues totaled less than $9 billion for the 2016 Rio Games, a significant portion of which was retained by the IOC rather than being given to Rio to help defray costs. Any net positive benefits from the Olympics for host cities must either result from enhanced economic activity during the Olympics, effects typically not supported by objective economic analyses (see, for example, Baade, Baumann, and Matheson 2010), or must stem from an Olympic Games legacy. Unfortunately, long-term benefits from hosting have also proved elusive, and the few studies that show Olympic-size economic benefits fall apart when Olympics hosts are compared with otherwise similar countries that didn’t host the event (Maennig and Richter 2012).

The escalating costs of the Olympics stem from numerous factors. First, the scale of the event has increased over time as the Olympics has become a victim of its own success. Over the past 50 years, the number of teams, events, and athletes has roughly doubled. Many of these sports require specialized infrastructure that host cities must build specifically for the Olympic Games; few potential hosts have preexisting world-class velodromes, swimming competition facilities, or championship track-and-field stadiums. And by their very nature, specialized venues often are of little use following the games, leaving a legacy of expensive white elephants. It is all too easy to find abandoned and crumbling Olympic venues just a few short years after the Olympics in host city after host city. Of course, even in terms of spending per athlete or per event, costs have still risen substantially, so other factors must be at play.

Security is another major cost. The Olympics have suffered two terrorist attacks (in Munich in 1972 and in Atlanta in 1996), which highlight the extent to which global symbols such as the Olympic Games provide a prime target for terrorist groups. Security costs alone for the Summer Olympics now routinely exceed $1.5 billion, a figure that has also risen as international tourists have flocked to the event.

Poor planning and cost controls or unrealistic projections also play an important role. As noted by Flyvbjerg, Stewart, and Budzier (2016), between 1960 and 2016, the average Olympic Games experienced cost overruns of 156 percent. These cost overruns stem from a combination of factors, including artificially low initial cost estimates, tight deadlines, mission creep, and in some cases significant corruption. In Rio, for example, the 2016 Summer Games were initially budgeted to cost $3 billion and instead came in around $13 billion as costs for planned infrastructure improvements, including a major extension to the subway system, skyrocketed. These large deficits led to cuts in public services, including health care spending, education, and public transportation, leading to widespread public protests in the run-up to the games.

Tokyo’s 2020 Summer Olympics experienced similar problems even before the one-year postponement due to the global COVID-19 pandemic drove costs up and expected revenues down. The original $7.3 billion budget had grown to an official figure of $15.4 billion and unofficial estimates of over $25 billion in true outlays. The construction expenditures for the new national stadium alone, which will be closed to sports fans but will be used for track and soccer events, totaled $1.4 billion—more than the cost of staging the entire 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles, even after accounting for inflation. The facility will also host significantly downsized opening and closing ceremonies, which themselves have an expected price tag of $118 million. The yearlong postponement, plus the additional costs of COVID prevention measures, has raised the costs by an additional $3 billion, and the local organizing committee and Tokyo’s hospitality industry stand to lose well over $2 billion from lost ticket sales, reduced sponsorship income, a ban on foreign visitors, and the elimination of ticketed spectators at most events.

Without a reasonable chance of short-term benefits or a long-term economic legacy, many cities, particularly those that rely on public input in decision-making, have signaled a lack of interest in bidding for the games. In the competition to host the 2022 Winter Olympics, no fewer than five potential host cities, all Western democracies, withdrew from the bidding process after voter referendums or polling data indicated a lack of public support, leaving only Beijing and Almaty, Kazakhstan, in the running. Similarly, Boston, Budapest, Hamburg, and Rome all canceled their bids for the 2024 Summer Games, leaving only Paris and Los Angeles standing. Faced with the very real possibility that no suitable city would step forward for the 2028 Games, the IOC took the unprecedented step of simultaneously awarding both the 2024 Summer Games to Paris and the 2028 Games to Los Angeles.

Of course, despite the dismal economics of the Olympics, the event remains wildly popular among sports fans and athletes. As many as 3.6 billion people worldwide tuned in to at least some portion of the 2016 Olympics in Rio, far more than for any other sporting event except the FIFA World Cup—which faces many of the same issues as the Olympics. Qatar is reportedly spending upward of $200 billion in its preparations to host the 2022 tournament. Still, representing their country in the Olympics remains the dream of many top athletes.

To its credit, the IOC recognizes the financial and social burdens of competing for and hosting the Olympics and acknowledges the need for reforms that reflect all stakeholder concerns and interests. The organization has proposed as part of its “Olympic Agenda 2020” that rather than continuing with its open bidding competition that rewards cities that promise the fanciest venues, the most luxurious accommodations, and the most spectacular ceremonies, it will instead evaluate bids based on economic (as well as environmental) sustainability. The IOC has also indicated that it will actively court cities that it believes can successfully host the games instead of encouraging entries from any and all cities—Sochi, for example—including those needing a complete civic overhaul to host an Olympic event. The very fact that the IOC awarded the 2028 Olympic Games to Los Angeles without even announcing a formal bidding process is an encouraging sign that the organization is serious about reining in costs. Sharing an increased portion of international television and sponsorship rights in order to help local organizing committees cover their costs of hosting would also be a positive step for the IOC. Of course, even if the IOC allocated all worldwide media and sponsorship revenue to the host city, it would still not come close to covering the cost of hosting the event in cities such as Tokyo or Rio.

Host cities also bear some of the responsibility for changing the dynamic. Too often hosting a major sporting event can be seen as a vanity project for local politicians or an economic boondoggle pushed by leaders in particular industries (such as hospitality and heavy construction) who stand to benefit. Host cities also often focus too specifically on the sporting venues and the pageantry of the event rather than using the event as a catalyst for broader economic change. For example, the recent Olympics most widely praised as being an economic success is the 1992 Barcelona Games. While the event overall was among the most expensive in Olympics history, topping $17 billion (in 2021 dollars), most of the money was spent on improving tourist amenities throughout the city rather than on facilities and operations during the three weeks of the event. These investments in general infrastructure have paid long-term dividends, and Barcelona has steadily climbed in the rankings as one of Europe’s top tourist destinations.

However, many economists suggest that more radical changes may be needed to guarantee the long-term survival of the games without imposing massive burdens on host cities. First, the Olympics could simply encourage hosting by region rather than by city. Even a large city like Paris or Los Angeles may not have the infrastructure to stage competitions in 33 separate sports or accommodate the expected influx of tourists, so expanding the Olympics to several cities can increase the available venues and tourist capacity. International football events are already moving in this direction. UEFA Euro 2020 was hosted in 2021 for the first time by cities across Europe rather by a single country. Unlike individual countries, Europe as a whole already has enough large stadiums for the entire tournament without requiring any new venue construction, which reduced the cost of staging the event.

Of course, the solution that likely makes the most sense economically it to simply establish a permanent site for the Olympics. (Given the history of the games, Athens is often suggested for the Summer Games.) Such a move would allow one-time construction of permanent venues instead of Olympic hosts trying to rebuild Shangri-la in a new city every four years (Matheson and Zimbalist 2021). Aside from eliminating white elephants, a permanent location would also allow the Olympic host site to retain the human infrastructure of skilled event managers with the knowledge and experience to keep costs down.

While cities have competed for years for the opportunity to capture Olympic gold, short-term and long-term benefits generally have proved inadequate to justify the cost of hosting the games. Skyrocketing price tags and disproportionate revenue sharing have generated Olympic resentment rather than reward. Without a sustained commitment by the IOC to provide cities a reasonable chance to benefit, the future of the Olympic Games is in jeopardy.

References:

Baade, Robert, Robert Baumann, and Victor Matheson. 2010. “Slippery Slope? Assessing the Economic Impact of the 2002 Winter Olympic Games in Salt Lake City, Utah.” Région et Développement 31:81–92.

Baade, Robert, and Victor Matheson. 2016. “Going for the Gold: The Economics of the Olympics.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30 (2): 201–18.

Flyvbjerg, Bent, Allison Stewart, and Alexander Budzier. 2016. “The Oxford Olympics Study 2016: Cost and Cost Overrun at the Games.” Saïd Business School working paper, Oxford, UK.

Maennig, Wolfgang, and Felix Richter. “Exports and Olympic Games: Is There a Signal Effect?” Journal of Sports Economics 13 (6): 635–41.

Matheson, Victor. 2019. “The Rise and Fall (and Rise and Fall) of the Olympic Games as an Economic Driver.” In Historical Perspectives on Sports Economics: Lessons from the Field , edited by John Wilson and Richard Pomfret, 52–66. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Matheson, Victor, and Andrew Zimbalist. 2021. “Why Cities No Longer Clamor to Host the Olympic Games.”Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, April 19.

Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF and its Executive Board, or IMF policy.